Governance and Politics when Democracy is at Risk

Paul Musgrave has recommendations for the coming lame-duck session. They’re all very sensible. Some, such as action on the debt limit and a big aid package for Ukraine, might actually happen. Others items on his wishlist, including DC statehood and Court expansion, have a snowball’s chance in hell; Manchin and Sinema won’t support them.*

The most important part of his post, however, is not Paul’s wishlist. It’s what he has to say about the politics of passing major structural reforms between November 8th and January 23rd.

This is just a special case of the precedent response: rules can be changed, and what evidence do you have that the next Senate Republican majority will be unwilling to change them to their advantage? There’s no strategic interaction here, just a chance to make progress or not.

The savvy response has to do with the other priorities for the lame duck. The budget, the NDAA, and all of the rest really do matter. Republicans could in fact make passing those priorities somewhat harder. The argument for being forward-leaning here is simply that there’s already a record of bipartisan achievement, and now it’s time to govern like a governing party. Set up the cots in the cloakroom and cancel Thanksgiving plans.

The political response is that there will be a public backlash. No, there won’t. (At the risk of being the bad guy in the Onion classic.) If Republicans win Congress back after January 6 and the Dobbs decision, then there is no more—meaningful—electoral penalty for norm transgression. Might as well get some priorities done [emphasis added].

In the “and now for something completely different” department, Josh Barro argues that Democrats have failed the first test of running to save democracy.

In countries where there is a real cross-ideological coalition to protect democracy, this is not how it works. In Israel and Hungary, coalitions of ideologically diverse parties have set aside their differences to run on very narrow governing agendas that are essentially about keeping the other side out. This approach has worked in some elections but not in others, but it hasn’t involved the Labor Party in Israel telling various right-wing anti-Netanyahu parties they must sign onto a full spectrum of left-of-center issue positions to share a coalition. This is how such coalitions engage in democratic accountability — if you’re going to tell people they must vote for your side to keep a dangerous authoritarian out, you also do what you can to make them feel ideologically comfortable within the coalition on issues besides elections themselves.

The examples here don’t help Barro’s argument.

Hungary and Israel are both multiparty systems. The coalition had almost no chance in Hungary; my guess is that Barro, like a lot of American political commentators, doesn’t fully grasp the extent to which Orbán has hollowed out Hungarian democracy (see Kim Lane Scheppele’s excellent article in the July issue of the Journal of Democracy). In Israel? Let’s check in on how that’s going:

While Israeli election results indicate a slim parliamentary majority for former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, they also represent a stunning triumph for Israel’s far right — a once fringe, aggressively anti-democratic, fundamentally racist movement that may soon control some of the country’s most influential positions of power.

(To be fair, Labor’s failure to run a joint list with Meretz didn’t help matters.)

The fundamental problem with Barro’s argument isn’t that he’s wrong, per se. In principle, Democrats should be opening their doors to—and even, in appropriate districts and states, nominating—more in the way of pro-democracy Republicans. However:

- It is not clear that they can do so without losing more votes on the left;

- Negative partisanship in a two-party system strongly undercuts the strategy; and

- The party is already an ideologically heterogeneous coalition—even if voters don’t perceive it that way.

So where do we go from here?

Once the 2022 elections are done, we’re all going to need to directly confront two features of the “new normal” in U.S. politics:

First, that we’re living through a period in which far-right views are effectively “normalized,” and not just in the United States. This means that pro-democracy parties will need to change how they engage with far-right ideas: as ones that a majority of voters remain uncomfortable with, but no longer view as dealbreakers.

Second, it’s just a matter of time before we go through a crisis worse than January 6th. Barring an electoral or lame-duck session miracle, the Democratic party has lost its chance to manage, let alone prevent, that crisis through routine political processes.

In light of current trends, the Democratic party may need to consider devolution. That is, restructuring itself as a loose confederation of different regional and state parties—ones that are positioned to compete in structural environments in which they cannot win elections unless they capture slices of the electorate that currently vote Republican.

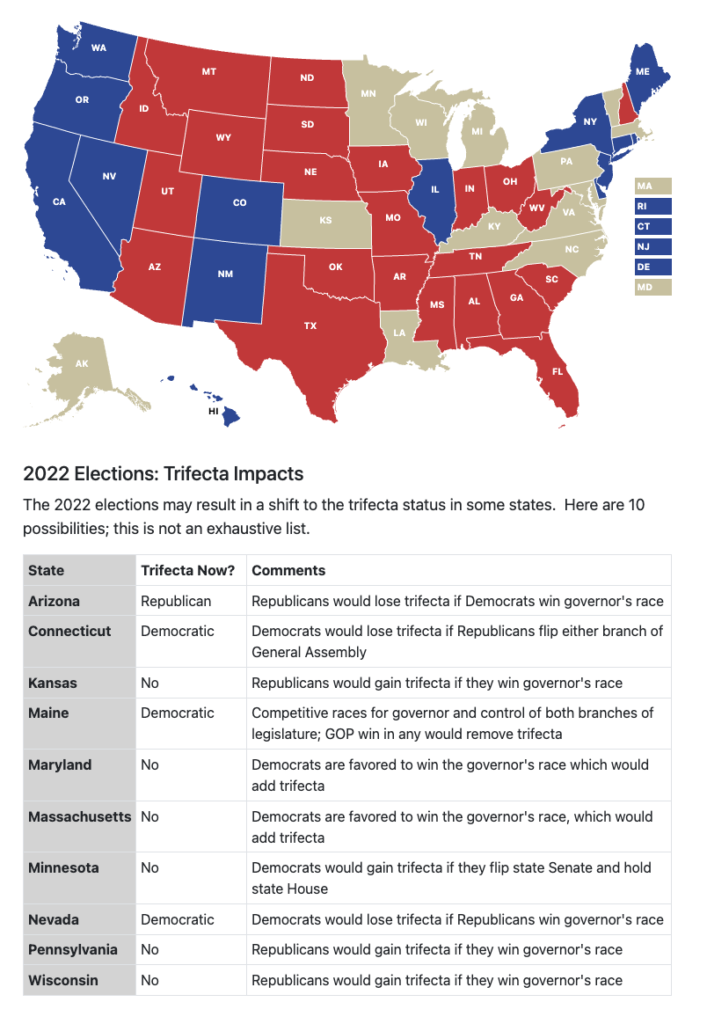

We’ve seen “lite” versions of this approach in places like Kansas, where cross-ideological coalitions have met with some success on the state level. Although Evan McMullin is likely to lose in Utah, future McMullin’s might pevail if they have access to an established party apparatus that maintains a truly distinct identity from that of the current national Democratic party.

The replacement of the Democratic party with a confederation of regional parties would entail something more like a parliamentary-politics approach to the House and the Senate. That is, leadership elections would have to involve explicit, ex ante bargains about policy. That way regional parties could point to precisely what concessions they’ve received in return for their support.

But unlike multiparty arrangements in first-past-the-post systems, a confederative arrangement would not require, say, center-right and center-left parties to compete with one another.

Do I really think this is possible? Not really. Still, I think that it is worth exploring what kinds of radical adaptations might be required if the GOP continues to dismantle American democracy.

*If 2022 is the “red wave” election that I’m expecting, then I wouldn’t be surprised if either Manchin or Sinema (or both) switch parties.