Erik Visits a (Non) American Grave, Part 2,064

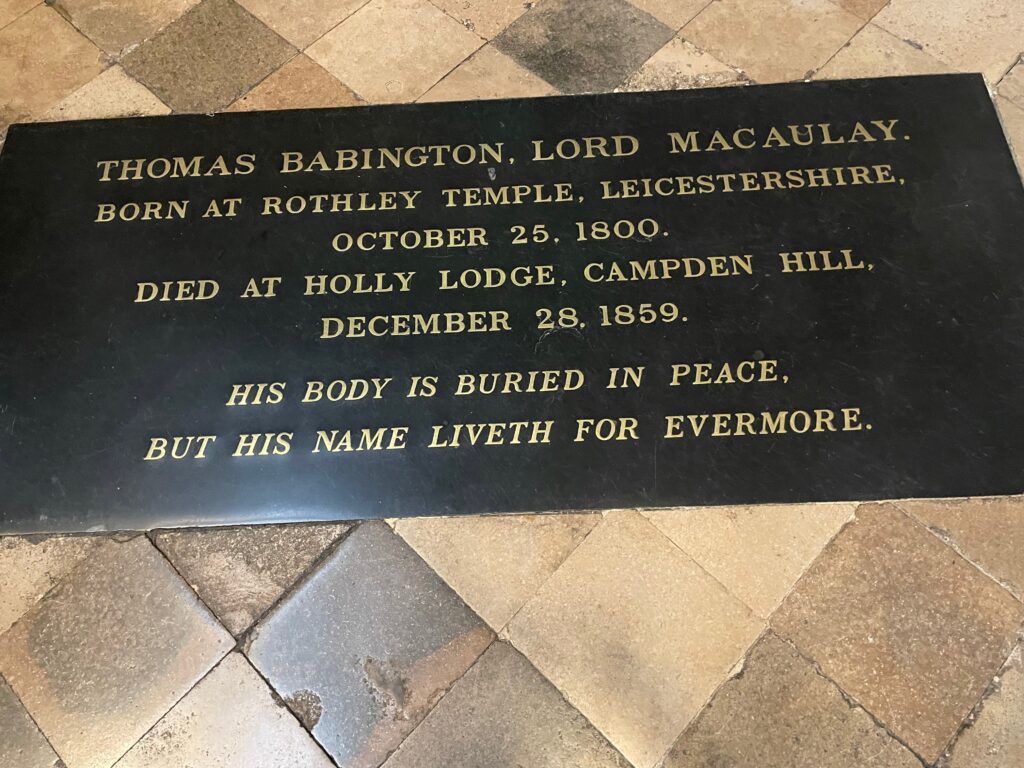

This is the grave of Thomas Babington Macaulay.

Born in 1800 in Rothley Temple, Leicestershire, England, Macaulay grew up well off, the son of a colonial officer, who also was an abolitionist, which is always a good reminder that just because one opposed slavery by no means meant they believed in some early semblance of modern equality or humanity. The kid was seen as brilliant from the time he was a small boy. So he got to go to all the best schools, ending up at Trinity College at Cambridge. He wrote prize-winning essays about literature but studied the law, taught himself several foreign languages, and showed a lot of interest in politics. Interestingly, in an anonymous article in these years he attacked his own father’s hypocrisy by going after abolitionists who argued for an “free” African peasantry tied to the land through debt.

Macaulay got a seat in Parliament in 1830, basically as a gift. This was the era just before the political reforms of that decade. It was a rotten borough and the Marquess of Lansdowne thought he should be in Parliament, so he was. From the beginning, Macaulay was not someone to sit around and just let things be. His first speech in Parliament was an attack on discrimination against Jews in Britain. He may have entered Parliament as a representative of the corrupt nature of British politics but he used his position to argue for the civil reforms needed and ended up winning a seat from Leeds after they were enacted. This is what someone with privilege should be doing–it’s not necessarily about how you got to power, it’s what you do when you get it. We all may have to swim in the same waters when it comes to life, but it doesn’t mean you accept it just because you were able to take advantage of it at one time. A good principle, I think.

But Macaulay ended up in India too, like so many super intelligent British upper class people in these years. Basically, he needed the money. His father had lost most of his money so it was up to him to support the larger family’s lifestyle. So he took a position on the Supreme Council governing India and was there from 1834 to 1838. His major goal at this time was to bring British style education to India (gotta teach those savages to be good little fake Englishmen after all) and he wrote a report called Minute on Education in India that laid this all out and was important in bringing British-style schools to the colonies. He also pushed to make English the standard language of education and to employ English-speaking Indians to be teachers of other Indians. A bit of context–evidently the main languages of education were Sanskrit or Persian, neither of which real Indians spoke any better than they spoke English. I guess education in Urdu or Hindi or the other languages was not something that could be considered though. But in all of this, Macaulay very much summed up the more liberal stance on colonization, which like white liberals of this period in the United States when it came to Native Americans, still held white supremacy as the central tenet, with these people having nothing like the sophistication or systems of learning that Europeans had and thus must be taught in “our” ways.

Macaulay also spent his time in India proposing a new penal code for the colony, which the government did not adopt at the time, but which it used as a model after the Mutiny of 1857. And let’s be clear about all of this–Macaulay was a total villain, someone with less than zero respect for anything about India. He’s very much seen this way in India today. There’s even a term–“Macaulayism” for Indians who reject their own past and culture and embrace the British. If you are a follower of Modi, for example, as so many Indian nationalists have become, Macaulay is the absolute idea of the colonist who is evil.

Macaulay returned to London in 1838 and entered Parliament the next year. Lord Melbourne made him Secretary of War soon after. But his real interest at this time was in copyright law, where he wrote quite a bit of what became that form of law in Britain. Generally, he opposed heavy copyright law, believing that education mattered more than copyrights. He represented Edinburgh in Parliament, but paid almost no attention to what people in that city wanted and that eventually cost him, as he lost his seat in 1847. But he was taken care of, being named rector of the University of Edinburgh in 1849. He returned to Parliament in 1852 after telling the people of Edinburgh that he would commit to absolutely nothing in order to achieve that, but if they wanted him, well, OK. I don’t know the context here really, but he was elected.

During the 1840s, Macaulay took on his beloved project of writing English history. The histories did not age well. Karl Marx took aim at the time, talking about how ridiculous his Whiggish version of history was. Marx said he was a “systematic falsifier of history.” Ouch. The History of England from the Accession of James the Second is his 1848 five-volume history of the topic, focusing on dramatic moments that he thought drove history. The first two volumes came out in 1848, the last three in the next few years. Every character he liked is a hero, every character he hated is a villain. Winston Churchill later wrote a four-volume biography of the Duke of Marlborough because he was so outraged about how Macaulay supposed defamed his ancestor. Macaulay wrote heavily for leading magazines and literary journals of the day, pushing his liberal ideas of improvement and progress. Of course, the idea that progress is something that happens and is inevitable and some sort of law of history is absurd, but people very much still believe that today.

In the end, Macaulay was your prototypical and even definitional 19th century British liberal, with all the belief in capitalism, the focus on free trade and the market as gods that must be served, the colonialism, the Whiggish vision of history. Few wrote more to push these ideas than Macaulay. There was no inconsistency in both supporting Jewish rights and forcing Indians to produce for the English state in this brain.

By the mid 1850s, Macaulay’s health started to fade. He had a bad heart. He didn’t do much politically and resigned his seat in 1856. The next year, he was raised to the peerage. He remained pretty active when he could be, working on the commission over who which historical figures would be portrayed in paintings in Westminster Palace. This led to the creation to the National Portrait Gallery in London, since there became a greater demand for accurate portraits, though it’s not as if British art history wasn’t already full of those given its predilections in the 18th century.

Macaulay died in 1859, at the age of 59.

Thomas Macaulay is buried in Westminster Abbey, London, England.

If you would like this series to visit 19th century American intellectuals, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. George Woodward Warder is in Chillicothe, Missouri and Orlando Smith is in Sleepy Hollow, New York. Previous posts are archived here and here.