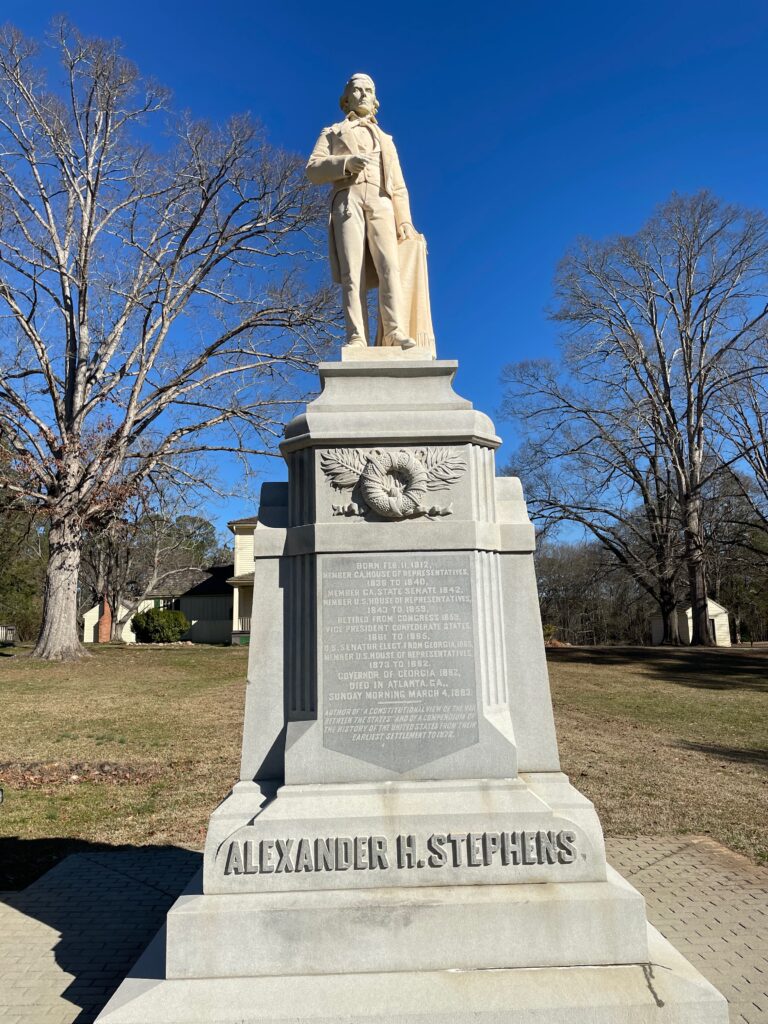

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,899

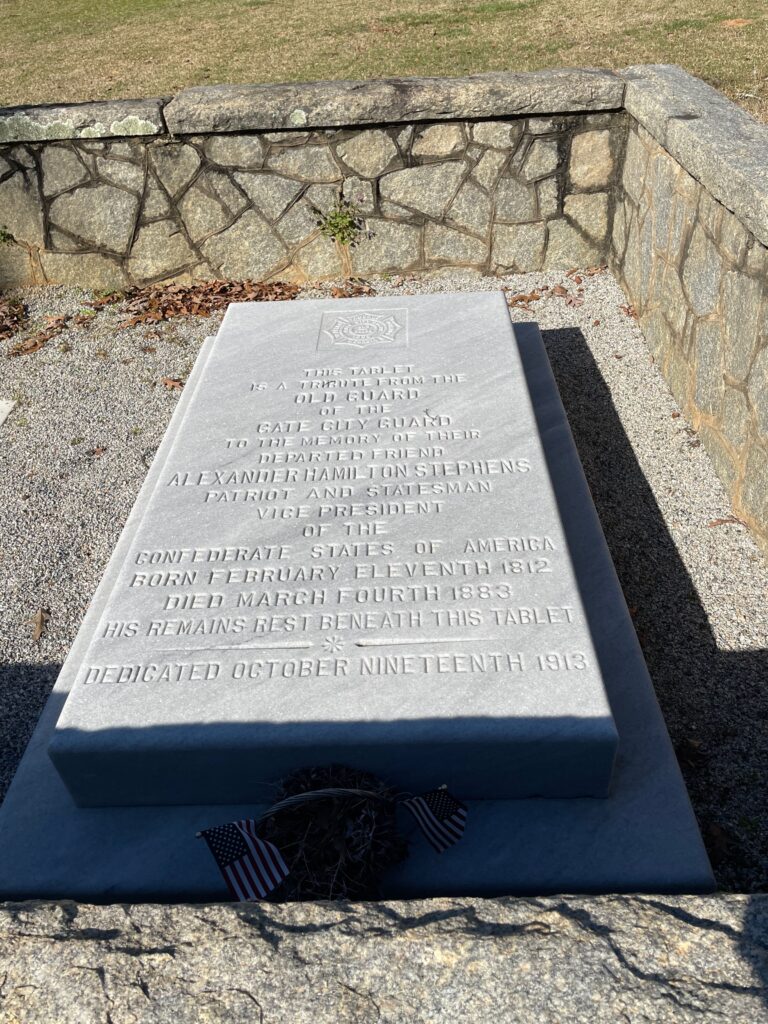

This is the grave of Alexander Stephens.

Born in 1812 in Crawfordville, Georgia, Stephens grew up in the slavery elite, at least at first. His mother died shortly after his birth, not sure if it was connected. Then when he was 14, his father and stepmother both died of pneumonia. He was downwardly mobile there for awhile, forced to live with distant relatives. But his relatives made sure he got a good education. Stephens went to Franklin College and then started a law practice back in Crawfordville.

Like a lot of these types, Stephens’ real interest was politics. He was a solid Whig, big believer in developing internal improvements. At this point, in the 1830s and early 1840s, both the Whigs and Democrats were national parties and they hoped to remain that way by sweeping any discussion of slavery under the rug. That was becoming increasingly impossible though, with John Tyler and then James Polk going all-in on the slavery question and making it almost impossible for a southern politician to operate without being openly pro-slavery. That would eventually put Whigs such as Stephens in an awkward position. Stephens himself served in both houses of the Georgia legislature and then was elected to Congress in 1842, where he would remain until 1859. For all his awfulness later, he actually actively opposed Polk’s Mexican War, which was a pretty unusual stance for a southern politician to take.

In fact, Stephens remained a unionist up to the point where the South committed treason in defense of slavery. He became a big supporter of the Compromise of 1850 and hoped that would keep the nation together. Of course it did not thanks to continued southern overreach on the Fugitive Slave Act, in Kansas, and in schemes to expand America’s slave empire into Mexico, Cuba, Honduras, etc. But by the mid-1850s, Stephens was a bigger part of the problem. When it became impossible for a southern politician to keep being elected as a Whig, he bent the knee and became a Democrat and an ally of James Buchanan over Kansas. He wanted the evil Lecompton Constitution passed that would have admitted Kansas as a slave state, over the desires of the people who actually lived in that territory.

Stephens decided not to run for reelection in 1858, but remained a power player in Georgia and the South. He was still a unionist, but when Georgia committed treason in defense of slavery, he went along without much trouble. Then of course he was elected Confederate Vice-President. That was a sop to the old unionists and Whigs, showing that the new Confederate government could unite whites across what were acceptable political perspectives for the white South. Once Stephens was in, he was all-in, even though he in fact had voted against secession himself in the Georgia convention where it did so. In fact, he annoyed other leading Confederates in the early part of the war for being so up front that this was all about slavery. He stated, in his famous Cornerstone Speech:

The new [Confederate] Constitution has put at rest forever all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institutions—African slavery as it exists among us—the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the “rock upon which the old Union would split.” He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted.

Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based on this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

What more does one need to know that the Civil War was treason in defense of slavery?

Now, that doesn’t mean that Stephens was particularly a fan of Jefferson Davis. He was not. He became more critical of Davis as the war went on as well, particularly over the Davis’ disinterest in democracy and suspension of habeas corpus. It’s not surprising really–Davis was a terrible choice for the Confederate presidency who constantly interfered with generals and who had absolutely no respect for even the white people of his wannabe nation, notoriously threatening to shoot women in Richmond rioting over food shortages, to note one infamous example. In fact, Stephens had almost nothing to do during the war. Davis had no interest in him and Stephens was largely not even in Richmond. He was occasionally given a mission to talk to the North, such as on prisoner exchanges and then in the February 1865 meeting with Abraham Lincoln at the Hampton Roads Conference to negotiate an end to the war, at which Lincoln mostly told him to shove it. But because Lincoln and Stephens had known each other from Whig politics back in the day, the president did order the release of Stephens’ nephew from a prisoner or war camp.

Still, Stephens should have been hanged for his role in the Confederacy. Alas, almost as soon as the war ended, the Union decided that the South was mostly right about race and so while he was briefly imprisoned, he was soon released. Then, in one of the great moments of outrageous temerity in American history, Georgia sent him to the Senate in 1866. That caused Congress to take over Reconstruction. What was the point of all the dead boys if all the same assholes were going to return to Washington and the ex-slaves were going to be returned to something very near slavery? Republicans refused to seat Stephens and the military was soon returned to the South, over Andrew Johnson’s furious veto, to occupy the South.

This kept Stephens out of Washington for awhile. Instead, he wrote a history of the United States in the late 1860s that argued the southern states seceding had been legal. But again, most Republicans were pretty curious about the South’s opinions about Black people once slavery was over. So as Georgia was “redeemed” from the horrors of Black people having rights, Stephens ran for Congress in 1873 and won and this time there was no question of not sitting him. He would remain in Congress until 1882. Then he became governor of Georgia.

But he did not remain governor for long, as he died in 1883. He was 71 years old. It’s not that old, but Stephens was a tiny, frail man, weighing only about 100 lbs and he seems to have just pushed himself too much and his body gave out.

Alexander Stephens is buried in Alexander Stephens Memorial Park, Crawfordville, Georgia.

If you would like this series to visit other Confederate leaders, you can donate to cover the required expenses to profile traitor scumbags here. Robert M.T. Hunter is in Loretto, Virginia and William Browne is in Athens, Georgia. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.