Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,667

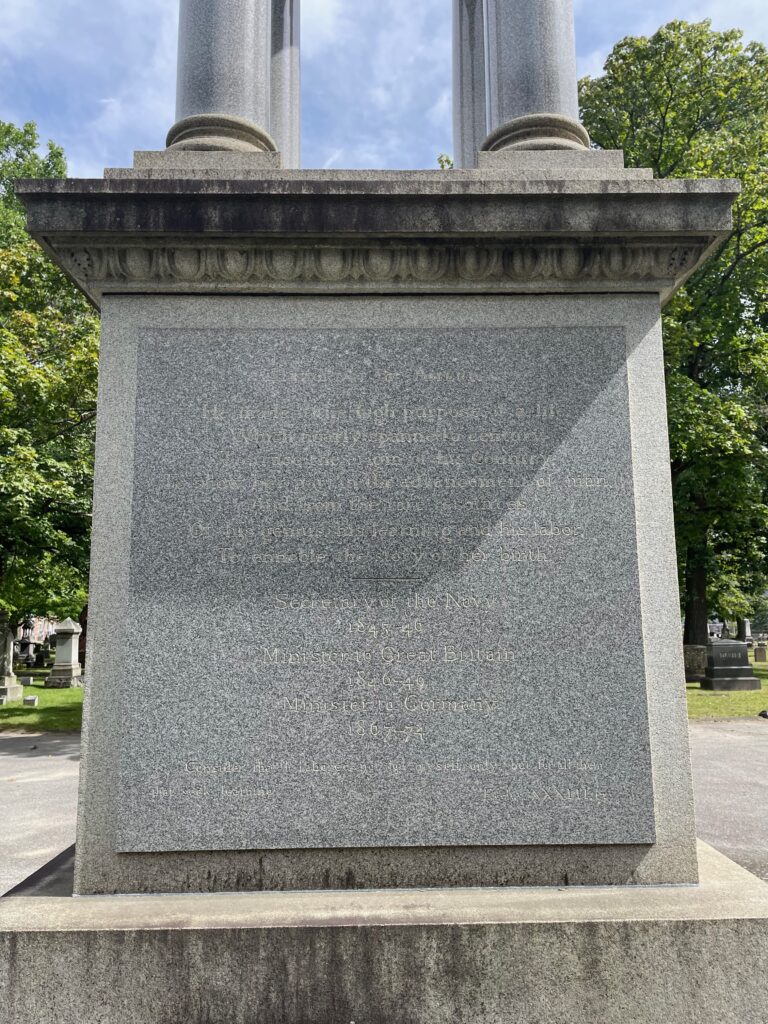

This is the grave of George Bancroft.

Born in 1800 in Worcester, Massachusetts, Bancroft came from old Purtian stock, which he loved. His father was a leading Unitarian minister who wrote a biography of George Washington. So Bancroft was an elite child of the Early Republic. He went to Phillips Exeter and then started at Harvard when he was 13, graduating in 1817. Then it was off to the German states for further study at the leading institutions of that language, just at the time when American elites started sending some of their kids there for the best education in the world, as they saw it. Bancroft studied in Göttingen and Berlin, got a doctorate in 1820 from the University of Göttingen, and then did the Grand Tour, where he met everyone from Goethe to Humboldt.

Bancroft came back to the U.S. in 1822. The initial idea was that he would be a minister, but that was not his interest by this time. He took a job teaching ancient languages at Harvard, but he hated it. Europe had changed him. He had become sympathetic to reform movements and the European revolutions. He thought Harvard was stuffy and backward. He came to support Jacksonian democracy over the post-Federalist society the rest of the New England elite supported. He was attracted to the romanticism rising in letters at that time. Basically, he had become a cosmopolitan returned to the provinces. Plus he wrote poetry, publishing his first work in 1823. So he was something of an outcast with his fellow elites in these years.

Bancroft left Harvard and started his own school in 1823, Round Hill School in Northampton. This was an early attempt to provide the newest education for the children of the New England elites. It didn’t really work out–it struggled along for a decade–but there’s a historical importance here in the transition of New England education from the post-Puritan years into the drastic changes overtaking the world in the 19th century. He also spent these years writing widely and promoting the idea of universal white male suffrage. He was even elected to the state senate in 1836 by the Working Men’s Party, but they evidently didn’t tell him ahead of time and he refused to take the seat.

Bancroft’s real project in these years was his History of the United States, the first real attempt to tell this story. It began to appear in 1834 and he worked on it, both expanding it and revising older volumes, all the way up to 1874. It ended up being 10 volumes and covering the entirety of the nation’s history up to 1782. It was a chronicle of progress by Puritans and their descendants and maybe some Virginians too, but let’s be clear, it was New England that mattered. As the great historian George Frederickson later stated of the book, its “universalist theory of national origins… made the American Revolution not only the fruit of a specific historical tradition, but also a creed of liberty for all mankind.”

Working on his history did require money and so he started taking government jobs. In 1837, Martin Van Buren appointed him Collector of Customs of the Port of Boston, which was a good patronage position that allowed Bancroft to pass some of that patronage down. Among those he hired was Orestes Brownson and Nathaniel Hawthorne. In 1844, Bancroft decided to run for office himself, governor. But that was a bad year for a northern Democrat, with the party deeply divided over the issue of Texas and slavery. Bancroft definitely supported the annexation of Texas, but also personally opposed slavery, which put him in a heck of a bind with a ticket headed by arch-racist James K. Polk. What it meant for Bancroft is that he lost the election.

But Bancroft lived with the contradictions. Polk needed someone from New England in the Cabinet and so he chose Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy, despite the fact that he had basically no political experience outside of a failed campaign and as a patronage employee. Let’s just say ability to govern was not exactly a high priority in the 19th century Democratic Party. But Bancroft did do one thing of note–he established the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. Now, for reasons that are unclear to me, Secretary of War William Marcy, doughface extraordinaire, had to step away from the job briefly and Bancroft also became acting Secretary of War for a month. It was at that very moment that the U.S. was ramping up its unjust attacks on Mexico to start a war in order to steal half that nation to expand slavery. So it was as Secretary of War that Bancroft ordered Zachary Taylor’s troops to advance beyond the internationally recognized boundary of southern Texas on the Nueces River to the Rio Grande, which everyone knew was Mexican land but which greedy Texans claimed too. That is what led the Mexican troops to attack and repel the invasion, which led Polk to lie to Congress and say American troops were unjustly attacked on American territory, and one of the darkest wars in American history got under way. So that’s some kind of legacy for Bancroft.

One of the things Bancroft had done a lot of work on was studying Oregon and he was considered an expert on the issue. So in 1846, he stepped down as Secretary of the Navy and was appointed Minister to Britain, where he helped work out the border as the British stepped away from what became the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. He did that for the rest of the Polk administration.

In 1849, now out of government, Bancroft came back to the U.S. and worked on his histories. He had plenty of money, so whatever. As a very strong Democrat, he was disgusted with the election of Abraham Lincoln. Like many Democrats, and even more than a few Republicans, he thought Lincoln was a total yokel. But Bancroft was still the odd Democrat who had not only stuck with the party but actively worked for its actions to promote expansion to extend slavery while genuinely disliking slavery. So he picked up his pen and wrote to Lincoln in support of emancipation. Lincoln wrote back, as he tended to do (it’s legit astounding how presidents spent their time in the 19th century) and they became close. In fact, Lincoln sent Bancroft a hand-written copy of the Gettysburg Address to sell to raise money at one of the fairs held late in the war to raise money in support of sanitation efforts in Army camps. He even gave a eulogy for Lincoln for Congress.

Andrew Johnson saw Bancroft as someone worth having in government somewhere and so he appointed him Minister to Prussia in 1867. Grant just kept him there after Prussia led the unification of Germany in 1871. He worked out the first of what became known as the Bancroft Treaties, which were agreements to work out naturalization and citizenship standards for immigrants and ensure that immigrants weren’t trying to become citizens to avoid military service at home (though I am pretty sure this still happened all the time with immigration to the U.S.).

In 1874, Bancroft returned to the U.S. and his histories. He died in New York in 1891, at the age of 90.

George Bancroft is buried in Worcester Rural Cemetery, Worcester, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other Secretaries of the Navy, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. John Mason is in Richmond, Virginia and William Ballard Preston is in Blacksburg, Virginia. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.