Gaming Notes

Happy leap day to you, LGM! I absolutely support the idea that leap day should be a day off to just do whatever, but in the real world in which this is a Thursday, we can at least talk about trivial things (I mean, I do that all the time, but today it’s for special reasons). My gaming over the last few months has had the same character as the months before. I’m still trying to find the perfect sweet spot between story-based and action-based, still discovering games that everyone else played ages ago, and still having some luck in finding out-of-the-way gaming experiences. Check out the reviews below, and chime in with your own recent gaming.

A couple of news items before we start. First, the puzzle game Rytmos, which I wrote about last year, has released a free expansion pack. I haven’t played it fully yet, but from the look of things it delivers exactly what the original game did—interesting and challenging puzzles with a background of learning about weird, little-known musical genres. In theory, developers Floppy Club could keep expanding the game forever, and while I assume that’s not their plan, it’s nice that they’ve served up this second helping.

Second, Lucas Pope, of Papers, Please and Return of the Obra Dinn fame, has a new game coming out next month called Mars After Midnight. That’s the good news. The bad news is that it’s exclusive to something called a Playdate (I’ve never been into gaming consoles but I think this is a slightly obscure platform just in general). Hopefully there will eventually be versions for PC and other platforms, but if not, this is my chance to remind you that Pope’s previous games are masterful and worth a look if you haven’t played them yet.

Chants of Sennaar (2023)

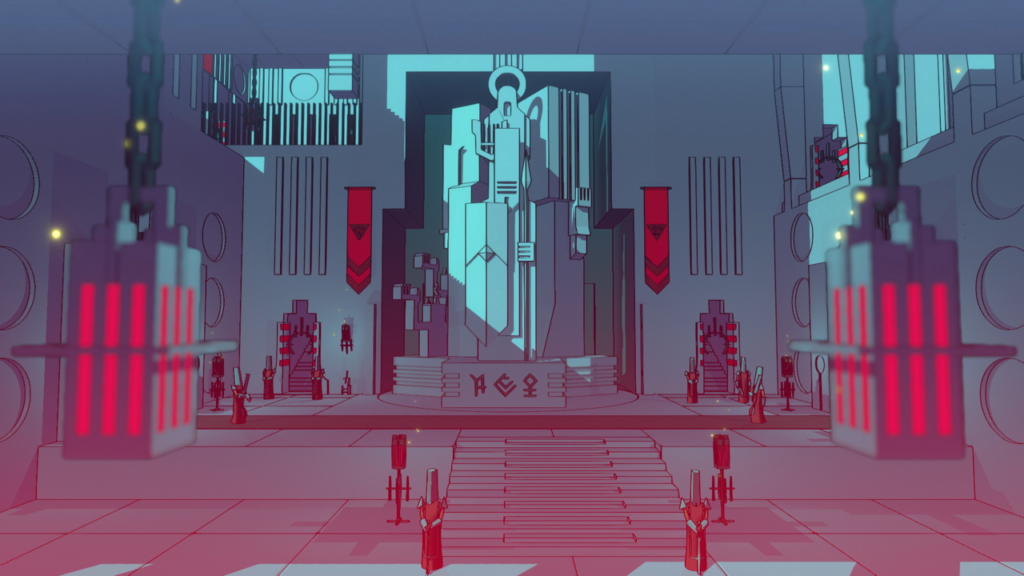

In French studio Rundisc’s delightful, compulsively playable game, you play a nameless figure who is trying to ascend a gargantuan tower. On each of its levels, your character encounters a very different society—peaceful monks, belligerent warriors, hedonistic artists—who each speak a different language. Each language needs to be deciphered: from context (the guy who needs you to unlock a door for him is probably asking for your help); from artifacts (the symbol at the center of a carving of people worshipping probably means “god”); and, as you advance in the tower levels, by applying your knowledge of one language to another. Along the way, you work out the mythology of each society, their views on the people above and below them, and ultimately, the secret history that ties them all together.

The translation mechanic, as well as the focus on anthropological investigation, will probably put a lot of players in mind of Inkle’s Heaven’s Vault (2019), a game that was an acknowledged influence on Chants of Sennaar‘s developers. At first glance, this might seem like an unkind comparison. The language of the ancients in Heaven’s Vault had an organic, expansive feel, and the texts you were asked to translate from it grew in complexity as your facility with it progressed. In contrast, the languages in Chants of Sennaar are quite simple, each made up of around thirty glyphs conveying concepts like “man”, “love”, or “death”. The mechanic for confirming translations is equally simple—once the game decides you’ve gotten enough context with a set of words, it presents you with a series of drawings into which you need to plug the correct glyphs.

It’s in the multiplicity of languages that the pleasures of Chants of Sennaar—and, arguably, its core conceit—can be found. It’s enormously satisfying to confirm your translations and become an expert in one level’s language, but every time you do, the game knocks you back to zero. The transition from one language to another often requires a conceptual leap: does the indicator for plural come before or after the noun? what is the verb-subject order? The linguistic transition is reflected in the game’s graphics, with each level having its own distinct visual sensibility, conveyed in beautiful line art that stresses the tower’s gargantuan architecture against your character’s smallness. It also affects the type of puzzles you encounter on each level. The warriors are suspicious of outsiders, so you need to practice stealth to get past them, while also learning some key terms so as to successfully pose as one of their own. On the level occupied by scientists, you’ll have to decipher their numbering system in order to work out a formula that allows you to advance to the next level. As your facility with the different languages progresses, you start to be able to translate between them, forming new connections and forging relationships between the different levels. If the words “tower” and “languages” rang some bells for you, this is very much a reference the game is courting. Its entirely satisfying conclusion requires you to use everything you’ve learned to facilitate radical communication.

Telling Lies (2019)

In my last roundup I mentioned finally getting around to playing Her Story (2016), Sam Barlow’s groundbreaking full motion video mystery game. Though I admired the game’s core mechanic, in which the player searches through video fragments by guessing keywords that appear in them, trying to piece together the events they depict, I also felt that the game represented more of a proof of concept than a complete gaming experience. In Telling Lies, Barlow, now with the backing of Annapurna Interactive, tries to reach that next level, with mixed results. The mechanic is largely unchanged, save for the twist that we now get both sides of each conversation, albeit as separate clips, requiring the player to guess what words the characters are reacting to in order to decipher the full context. Unlike Her Story‘s shoestring production, however, Telling Lies has obviously had vast amounts of cash poured into it. The video quality is higher, the locations are more varied, and the cast is stacked with some well-known faces from film and TV.

Telling Lies follows David (Logan Marshall-Green), an undercover FBI agent who is trying to infiltrate a Detroit environmentalist group whose protests against a proposed pipeline, he believes, are about to turn violent. Most of the clips in the game depict David’s video conversations with three women: his wife Emma (Kerry Bishé), a nurse in LA, who first cheerfully and then with increasing frustration discusses the challenges of carrying on their life without him, including parenting their young daughter; Ava (Alexandra Shipp), a young activist whom David courts as a way of gaining entry and acceptance into the group; and Max (Angela Sarafyan), a cam girl with whom David has some of the few honest exchanges in his life, discussing truthfully his mission, his feelings for Ava, and his complicated history with Emma, while trying to unravel the multiple, conflicting life stories she has told him.

It’s a more grounded story than the one Her Story delivered, and the multiplicity of perspectives and warring narratives makes it more challenging to untangle (it will, in fact, take watching a few clips before it becomes clear that David, the wannabe activist in Detroit, is not who he claims to be). There are some powerful character arcs here—Emma’s dawning realization, once she’s out from under his influence, of how overbearing David’s presence in her life has been, and how unhealthy the genesis of their relationship was; Max’s fleeting hints of annoyance at having to cater to the fantasies of self-absorbed men, including David’s fantasy of being able to see the real her. David himself is an impressively complicated creation, genuinely loving and devoted towards his daughter, but incapable of honesty with anyone more mature, and prone to delusions of heroism. He reacts with outrage (and a barely-suppressed glee at being able to play the hero) when he learns that Ava was sexually abused by another member of the group, but never stops to consider that what he is doing to her is no different. (In addition, the game is very clear on the fact that it’s David who is pushing the group towards violence against the pipeline, creating the terrorists he plans to arrest.)

In the context of 6-10 hours of burrowing through video clips, however (much of which is spent watching actors reacting to the unheard, other side of the conversation), these character flourishes can eventually start to seem a bit thin. The thrill of investigation that made Her Story so compulsive is still present, and eventually rewarded by some dramatic twists to several of the character’s stories. But the nonlinear format means that these twists are not the climax of the game—as in Her Story, there is no real win or lose condition, just the player deciding they’ve had enough and triggering the ending. By the time you get to that point, it’s a bit unclear whether all the hard work you’ve put into unraveling the plot was truly worth it. This may be a fundamental flaw in the two games’ mechanic, or it could be that Barlow is still searching for the perfect story and execution to make use of it. But Telling Lies, despite its many improvements on the original, is not quite there yet.

What Remains of Edith Finch (2017)

In my continuing quest to arrive very late to some of the biggest games of the last decade, I finally played What Remains of Edith Finch. It’s the game that put publishers Annapurna Interactive on the map, and represents perhaps the fullest flowering of the walking simulator craze of the last decade. Edith Finch follows its title character as she returns to her ancestral home, a secluded cliffside mansion on an island in the Pacific Northwest, whose wrongness is signaled from the first moment by its bizarre structure, with additions wrapping around it and reaching into the sky in a misshapen, rickety-looking tower. Edith is the last surviving member of the Finch clan, who since settling in the US in the early 20th century have met with one misfortune after another, dying or disappearing in grotesque and mysterious ways, often in their childhood or youth. After each death, the deceased’s room was sealed up, and Edith scrambles through secret passages, across walkways and branches, and over rooftops to access each room and witness the story of each of her relatives’ demise.

It’s this structure of nesting stories, each told in a different genre and storytelling mode, that is Edith Finch‘s main claim to fame, and its execution is deeply impressive. Some of the stories are brief—a few slides that reveal the fate of patriarch Odin, who drowned in sight of the island while trying to transport his whole house from Norway to the United States (I know this is a game, but surely someone in the development team should have mentioned the geographical issues here)—while others are involved narratives. Some are told in the first person, while others are mediated through different tellers and even different genres, such as a horror comic that claims to explain the fate of Edith’s great-aunt Barbara, a former child star who was murdered in her teens. Some fates are enigmatic—a flipbook shows Edith’s brother Milton, an aspiring artist, drawing a door and disappearing into it—while others are mundane or metaphorical, such as the elaborate fantasy world constructed by Edith’s other brother Lewis to distract from the tedium of working in a fish cannery. There’s a degree of player participation in each story, but here too the game is interestingly (and effectively) variable. You can direct movement in some of the comics panels of Barbara’s story, but the game also knows when to take the reins. Other stories, however, are full mini-games, with differing degrees of success. An early chapter in which you embody different animals on the hunt is eerie and immersive, while a later one in which you manipulate the toys in a toddler’s bath to cause an accidental drowning is both hard to accomplish and in spectacularly poor taste.

For all these stylistic and storytelling flourishes, what’s most remarkable about Edith Finch is how it manages to tie them all together with an awareness of the Finch family’s growing dismay, desperation, and grief, as they try to make sense of their tragedies and move on from them. Whether they believe in a curse, or chalk it all up to bad luck, or suspect sinister forces at work in the house, the surviving Finches keep trying to rebuild their lives—which makes it all the more heartbreaking when they, too, end up succumbing. Developers Giant Sparrow seem, however, to have been made uncomfortable by the idea of ending on this note. The fact that they choose not to commit to the hints of Lovecraftian horror they’ve sprinkled throughout their story, and never explain the reason for the Finches’ fates (or whether there even is a reason) is a perfectly valid choice, one that in some ways even intensifies the game’s effect. But their attempt to wring some solace from the game’s ending, to try to argue that there is something consoling or even inspiring about the litany of horrors and tragedies we’ve just spent several hours witnessing, is deeply unconvincing. It’s a failure of nerve, a bum note at the end of what until then had been an impressive, if also deeply sad and upsetting, narrative experience.

Stray Gods: The Roleplaying Musical (2023)

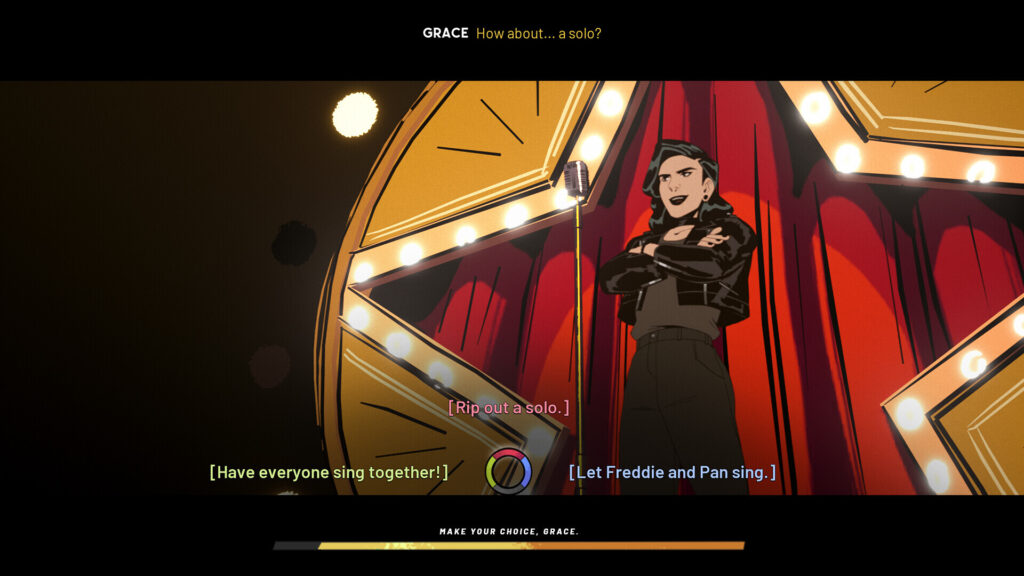

Given my well-documented antipathy towards games that require shooting, fighting, or any sort of key-mashing to progress in, you’d think the visual novel category would be something I’d have already spent time exploring. But—judging from this early foray, a gift from my brother—it seems that I need some feeling of control over my progress to really enjoy a game. Or, alternatively, the story needs to be a bit more compelling. In Stray Gods, you play Grace, an aimless college dropout whose life revolves around a struggling band, who is granted the powers of Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. Turns out the Greek gods are real and living in the modern world, and they can pass their powers to mortals when they die. The current leadership of the gods suspect Grace of killing Calliope to gain her powers, forcing her to investigate Calliope’s death—along the way, learning more about the gods’ experiences in the modern world and the soapy dramas that have fermented between them—in order to prove her innocence and save her own life.

Despite its presence in the game’s subtitle, roleplaying is a very minor component of Stray Gods‘s gameplay. You get to choose Grace’s character attributes, which affects her dialogue options, but these don’t seem to influence the gameplay very much. Plotwise, Stray Gods seems very fixed in its progression, and although it is possible to affect minor subplots, including who Grace romances, I’m not sure there is an ending in which Grace fails in her task and loses her life. More important is the word “musical”. Grace’s powers are, after all, the powers of a muse, and she gathers information and influences the people she meets by causing them to break out into song. The most clever and interesting aspect of the game is that while singing, you can choose different lyrics that not only change the song, but the feelings of the people singing, leading them to certain actions and decisions. This puts a lot of the pressure for the game’s success on its large voice cast. Its developers, Australian studio Summerfall Studios, have gathered some of the biggest names in the business—people like Laura Bailey, Ashley Johnson, and Troy Baker—as well as others, like Rahul Kohli, who are better known for live action, and a cameo from an absolute stalwart of the Broadway stage.

What this means, unfortunately, is that Stray Gods is one of the those projects that has a high concept and a lot of money on the production end, but which doesn’t seem to have put enough work into fine-tuning its ideas or perfecting its execution. “Figures from legend and mythology live in the modern world” is, after all, an extremely common fantasy premise, and Stray Gods not only doesn’t do much to set itself apart from the pack, it doesn’t seem to have taken into account how familiar its audience will be with stories of this type—it is, for example, extremely weird that Grace is not only ignorant of even the most famous Greek myths, but hasn’t read or watched anything inspired by them, like Sandman or The Wicked + The Divine. The songs, meanwhile, are sometimes charming, but even at their best they sound like the product of someone who has listened to the Hadestown soundtrack on repeat too many times. Perhaps because of the need to write three or four versions of each one, they end up feeling very generic, and not a single one has continued to reverberate in my head after finishing the game. All of this might have been less of a problem in a game that required more active participation, but when much of the gameplay experience of Stray Gods involves sitting back and letting the story play out, there’s more time to notice the problems in that story. I might end up going back to the visual novel category, but I’ll be looking for something with a bit more storytelling verve next time.

The Forever Labyrinth (2024)

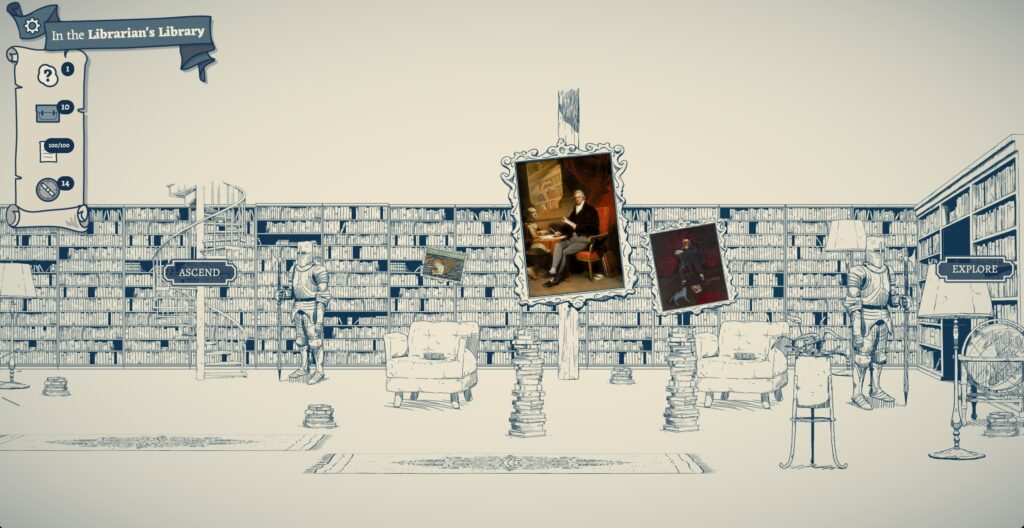

Barely two months after releasing one of the most enjoyable games of 2023, A Highland Song, Inkle studios returned with The Forever Labyrinth, a web game developed for Google Arts & Culture, a service that carries high resolution images and recordings of cultural artifacts. In the game, your character is drawn into the titular labyrinth, which holds hundreds of paintings, some famous and classical, some avant garde, and some just weird. Each room in the labyrinth is arranged according to a theme, which include the obvious—war, flowers, castles—and the bizarre—smiles, mustaches, boots. Though it’s possible to walk between the labyrinth’s rooms, a more important method of navigation is to identify an element in a painting that matches the room you want to get to, and travel through it. As you progress, a mysterious figure urges you to discover the center of the labyrinth and the power that lies there—a quest that is hampered by your encounters with other inhabitants who appear to have been gathered from different periods in history, by a sinister monster that dogs your steps and closes off passages behind you, and by scattered diary pages that suggest a more complicated history.

There are some very typical Inkle flourishes to The Forever Labyrinth‘s gameplay. Like most of their games, it needs to be played more than once to be fully appreciated, and even once impactful events occur in the story—once you’ve found the center of the labyrinth, or even caused its destruction—there is still more to explore and discover. But the most interesting thing about its gameplay is the way it uses players’ expectations against them. The natural impulse of an experienced player will be to try to map the labyrinth, to work out where the room of hats sits in relation to the room of clouds. But as you play, you realize that the actual key to navigating the labyrinth isn’t spatial, but conceptual. You have to understand how the labyrinth works, and how to use the paintings, which sometimes involves solving riddles that point in the direction of the right painting to proceed through, or creating a new painting that will take you where you need to go. Only this way can you evade the monster, and follow the various stories that take place within the labyrinth, learning about the person who created it, solving the problems of a Victorian detective or a Spanish conquistador, and outsmarting the figure who is trying to use you to gain control of it.

Despite all this wealth of storytelling, The Forever Labyrinth isn’t a particularly plot-oriented game. Its disparate elements, which include spaceships, locked safes, and vineyards, don’t fit together into a coherent whole, and aren’t really meant to. Fittingly for a game in which your character can travel from “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” to “Nighthawks”, its effect is much more vibes-based. The fun of it lies in figuring out the labyrinth’s rules and learning to master it, and as in all Inkle games, there is a real feeling of accomplishment as you achieve this (and the game is very good at handing out intermediate achievements to make you feel that you’re progressing). Though I must, in all honesty, point out that the web interface is a bit finicky (I’ve had to erase my progress and restart a couple of times) that really hasn’t dampened by enthusiasm for this weird, delightful game, which mixes so many strange concepts together into something that is almost instantly compelling.