Erik Visits an Non-American Grave, Part 1,943

This is the grave of Frederic Leighton.

Born in 1830 in Scarborough, Yorkshire, England, Leighton grew up in a family of very well off doctors. His grandfather had been the personal doctor to Tsar Alexander I and Tsar Nicholas I in Russia, for example. Which given medicine at the time didn’t necessarily mean he knew anything, but that’s just par for the course at the time. Anyway, Leighton could do whatever he wanted. His father made sure his son would have a hefty allowance through his whole life. Leighton did not want to follow his family into the field of medicine. Instead, he wanted to become an artist.

Leighton went to University College, London and then went for a long stint of art training on the continent, with the best teachers out there. In fact, in 1847, still only 17 years old, he was in Frankfurt, where he met the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. He convinced the philosopher to sit for a drawing and that remains the only full length painting of him ever. He would spend much of his life in Europe. Of course his family were extensive travelers to begin with, as the Russian connections suggest. He would do pretty typical travel for a man of his ilk–lots of France, lots of Italy, some Greece. And as the orientalist craze rose, he would go to places such as Morocco and the Ottoman Empire too.

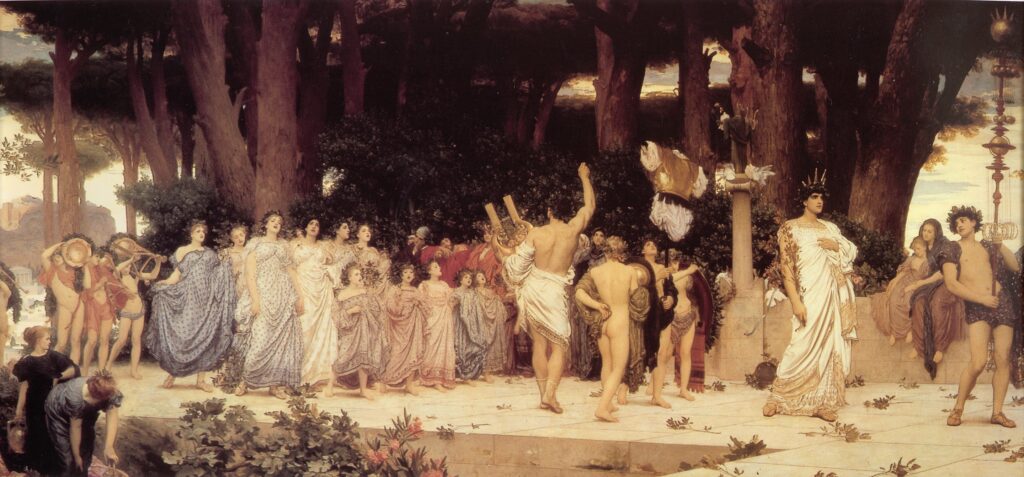

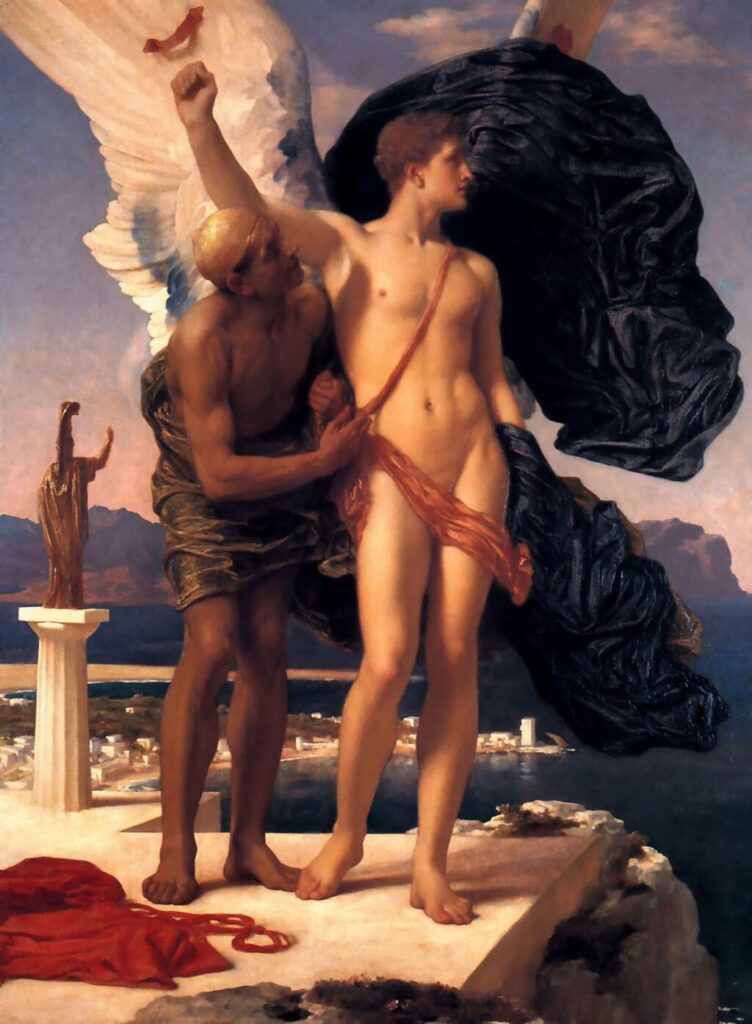

Leighton became a very standard painter of the British school–highly respected and talented, but not exactly breaking a lot of new ground with his work. You could describe much of British art in this way. Outside of Turner, there wasn’t a lot of British artists in the nation’s painting heyday of the 18th and 19th centuries as exactly transforming the art world, but capable work that reflected the upper class lifestyles of the era? For sure. He moved to London in 1860. There, he was part of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, bringing back the principles of 15th century Italian art to apply to 19th century subjects. This really fit Leighton’s world–deeply Christian, reflecting the romanticism of the time and thus rejecting the classical influences of the Enlightenment, not much interest in social issues and a lot of interest in beauty for its own sake. It’s more accurate to say that Leighton was a secondary member of this movement, being a bit younger than the founders, but he was still an important figure within it.

When Elizabeth Browning Barrett died in Florence, her husband Robert Browning had Leighton design the tomb. This marks a first in this series, covering not only the dead but also the tomb designer for the dead. The chances that this would happen in two European cities seems remote, but hey, someone has to travel to Europe and I guess it will just have to be me.

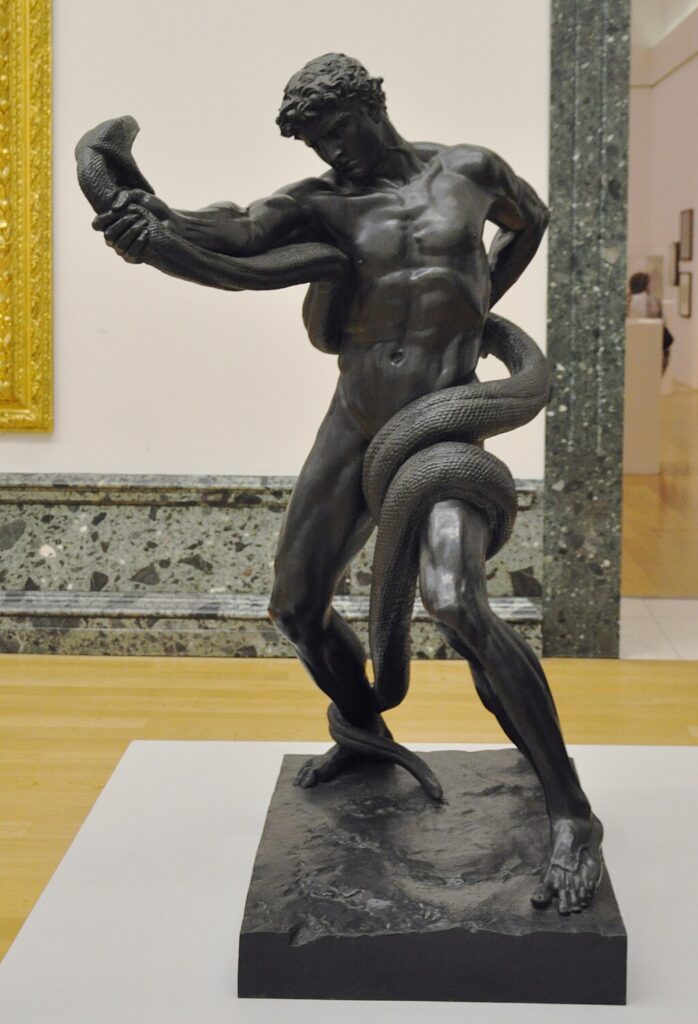

Leighton moved significantly into sculpture in the 1870s and that was well-received. An Athlete Wrestling with a Python has a claim to be the most significant piece of sculpture produced by an English artist in the 19th century. I don’t have the ability to check that claim, OK, but I do like it and you can see it below. At the very least, it started a new school of sculpture in the UK, called, uncreatively, New Sculpture. The idea behind this was free-standing figures with references to mythology and an emphasis on naturalism. The name wasn’t coined until 1894, by the critic Edward Gosse, but even then, it was Leighton’s sculpture seen as the movement’s progenitor. Its overall influence, like the rest of Leighton’s art, hasn’t held up much. It was seen as a check to Auguste Rodin and those dirty Frenchmen, but let’s just say that Rodin is much more beloved today than Leighton or any other limey artist of the time.

Outside of his art, Leighton really liked to play soldier. He helped create the 38th Middlesex Rifle Volunteer Corps in the British Army Reserve with other artists. It became known as the Artists Rifles. This came about as part of the nationalist fear of a French invasion of the Britain after Orsini attempted to assassinate Napoleon III and it was discovered that the assassin had British ties. The French were not stupid enough to try this, obviously. But that didn’t stop eager young men from dreaming of killing some frogs. Leighton and Henry Wyndham Phillips, another painter, were the first commanders of the unit. Later, the regiment became more of a broad upper-class and professional regiment that just had more than the average number of artists in it. It lasted through World War I, when most of its members were killed and the romance of war disappeared for a little while, though alas, not forever. It spent most of the 20th century as an officers training corps.

Unsurprisingly, Leighton fell completely out of style when modern art hit. In fact, he, like so many of his peers, haven’t recovered in terms of artistic influence. Whether that is justified or not, I don’t know. I am not a painter, so I can’t really speak to it. I can’t say his works move me in any way and I would pretty infinitely rather see almost any modern artist not named Andy Warhol instead. But whatever, I guess you don’t paint for the future, you paint for the present and he was certainly well-compensated for his work during his life.

Perhaps the most exciting thing about this post is that one day before he died, Leighton was made a peer, which would end upon death. This makes him the shortest lived peer in British history. That happened in 1896. He was 65 years old. It doesn’t seem this was some last second honor for a dying man. It was a heart attack that felled him, not some obvious illness.

Let’s take a look at some of Leighton’s work:

In short, Leighton is who you see if you mistakenly go to the Tate Museum in London instead of the Tate Modern.

Frederic Leighton is buried in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London.

If you would like this series to visit 19th century American artists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Mary Cassatt is in France if you want to send me back across the pond for more of this fine, fine art history. Frederic Remington is in Canton, New York and Thomas Moran is in East Hampton, New York. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.