Art of the Moment

I was a big fan of Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, which I thought was a super book, and I was excited to see that she’s published her next novel. But, while it seems like a good book, can I read a novel that is about the horrorshow developing upon us every day?

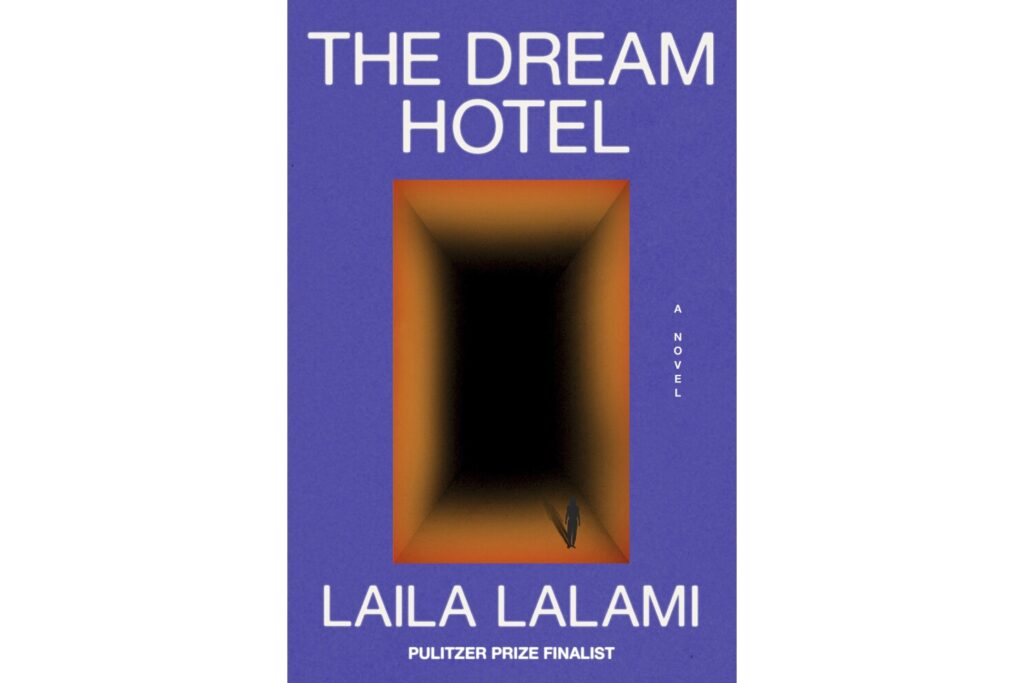

Laila Lalami’s disturbing new novel, The Dream Hotel, raises an existential question: How to read dystopian fiction when what has been imagined is now a familiar, quotidian reality? Lalami’s protagonist, a thirty-eight-year-old American-born academic and archivist at the Getty Museum named Sara Hussein, is pulled aside by functionaries from the government’s Risk Assessment Administration (RAA) when she arrives at Los Angeles International Airport after attending a conference in London. An algorithm has flagged her as “an imminent risk” for a crime she has not committed, based in part on her dreams. Sara is then remanded to a “retention center” for a “forensic observation” until she lowers her “risk score”—an inscrutably derived number that supposedly represents the likelihood of committing a crime in the future. A long-standing piece of legislation, the Crime Prevention Act, gives authorities the power to incarcerate anyone they deem potentially dangerous. A majority of Americans—62 percent—support this “pre-crime” law, because it promises to prevent misconduct before it happens.

That is the pretext for the fictional world Lalami has created. Perhaps by chance—or perhaps she herself has an uncanny ability to anticipate crimes before they have happened—real life caught up to her imagination. In March—the month Lalami’s book was published—Rümeysa Öztürk, a Turkish doctoral student at Tufts University, was abducted by a group of masked men as she walked down the street in Somerville, Massachusetts. The men, it turned out, were agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). After being hustled into an unmarked car, Öztürk was shuttled between a number of government lockups, landing finally at a detention center in Louisiana, where she sat for six weeks, charged with no crime.

Rather like Sara Hussein, Rümeysa Öztürk was singled out by the government for her thoughts: she had coauthored a March 2024 opinion piece in the Tufts student newspaper decrying Israel’s military operation in Gaza. The government justified holding Öztürk by claiming that she was “involved in associations that ‘may undermine US foreign policy by creating a hostile environment for Jewish students and indicating support for a designated terrorist organization.’” (Note that the government was not making the case that Öztürk herself was a member of those organizations.) When she was finally released—though she still faces deportation—US District Court Judge William Sessions III stated that “there is absolutely no evidence that she has engaged in violence or advocated violence.”

….

The Dream Hotel is different. In it it’s the law, randomly applied—not descent or status—that marginalizes people. Once Sara is in the clutches of the RAA, she is sent to Madison, an elementary school that has been repurposed as a holding facility run by a private company called Safe-X, for a mandatory three-week observation period. But do not call it a prison, and do not call the women at Madison prisoners. As Lalami describes it, “The retainees have to eat what they’re given, do what they’re told, sleep when the lights are out, but they’re considered FUO. Free, under observation.”

Much of the novel is given over to Sara’s day-to-day life at Madison—the friendships and alliances among the women, Sara’s longing to return to “real” life, visits from her husband and young children, her fear and frustration as those visits diminish, the cruelties and indignities exacted by the guards, and her estrangement from life as she has known it and expected it to be. Lalami is a subtle polemicist, which is to say that she doles out Sara’s pain and depredation by degrees so that it never feels contrived or sensational. Over time Sara’s trajectory begins to resemble the first four of Kübler-Ross’s stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, and depression. “What has retention taught her these last few months?” Lalami writes.

It goes on, as you can read.

I have never embraced escapism and I don’t want to embrace it now. But when you are in a constant state of depression and terror and despair about what is coming and when you see basically no way that this is going to get better (which is how I feel), how do you deal with it in art. It’s also why I have trouble engaging in the growing literature around climate change. It’s not just that there’s no remove, it’s that the description is of the future of an America and a world that has gotten demonstrably worse during my lifetime. Maybe the despair of art of the present is more than I can mentally handle. And maybe that’s OK.

But how are you all processing the current horrors through whatever you do for culture, however you define it?