Our American meritocracy

Sometimes unsurprising results are still worth reporting on:

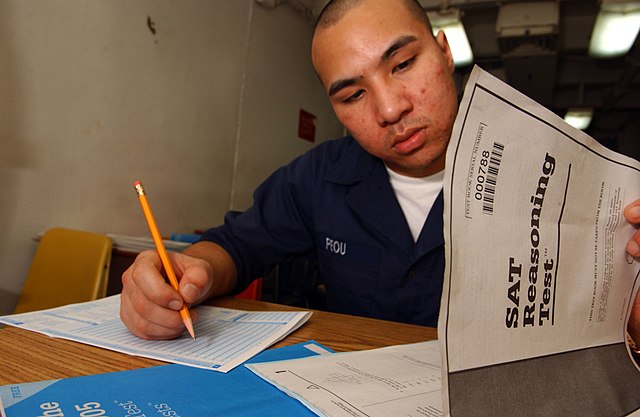

New data shows, for the first time at this level of detail, how much students’ standardized test scores rise with their parents’ incomes — and how disparities start years before students sit for tests.

One-third of the children of the very richest families scored a 1300 or higher on the SAT, while less than 5 percent of middle-class students did, according to the data, from economists at Opportunity Insights, based at Harvard. Relatively few children in the poorest families scored that high; just one in five took the test at all.

The researchers matched all students’ SAT and ACT scores for 2011, 2013 and 2015 with their parents’ federal income tax records for the prior six years. Their analysis, which also included admissions and attendance records, found that children from very rich families are overrepresented at elite colleges for many reasons, including that admissions offices give them preference. But the test score data highlights a more fundamental reason: When it comes to the types of achievement colleges assess, the children of the rich are simply better prepared.

The disparity highlights the inequality at the heart of American education: Starting very early, children from rich and poor families receive vastly different educations, in and out of school, driven by differences in the amount of money and time their parents are able to invest. And in the last five decades, as the country has become more unequal by income, the gap in children’s academic achievement, as measured by test scores throughout schooling, has widened.

“Kids in disadvantaged neighborhoods end up behind the starting line even when they get to kindergarten,” said Sean Reardon, the professor of poverty and inequality in education at the Stanford Graduate School of Education.

“On average,” he added, “our schools aren’t very good at undoing that damage.”

In the wake of the Supreme Court decision ending race-based affirmative action, there has been revived political momentum to address the ways in which many colleges favor the children of rich and white families, such as legacy admissions, preferences for private school students, athletic recruitment in certain sports and standardized tests.

Yet these things reflect the difference in children’s opportunities long before they apply for college, Professor Reardon said. To address the deeper inequality in education, he said, “it’s 18 years too late.”

In addition to how deeply educational qualities are rooted, the chances that the end of race-based affirmative action will lead to widespread efforts to address class imbalances in college admissions are roughly the same as the odds of Matt Patricia making the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In the vast majority of cases “class not race” was just a bait-and-switch.