Roundtable on Goliath by Tochi Onyebuchi at Strange Horizons

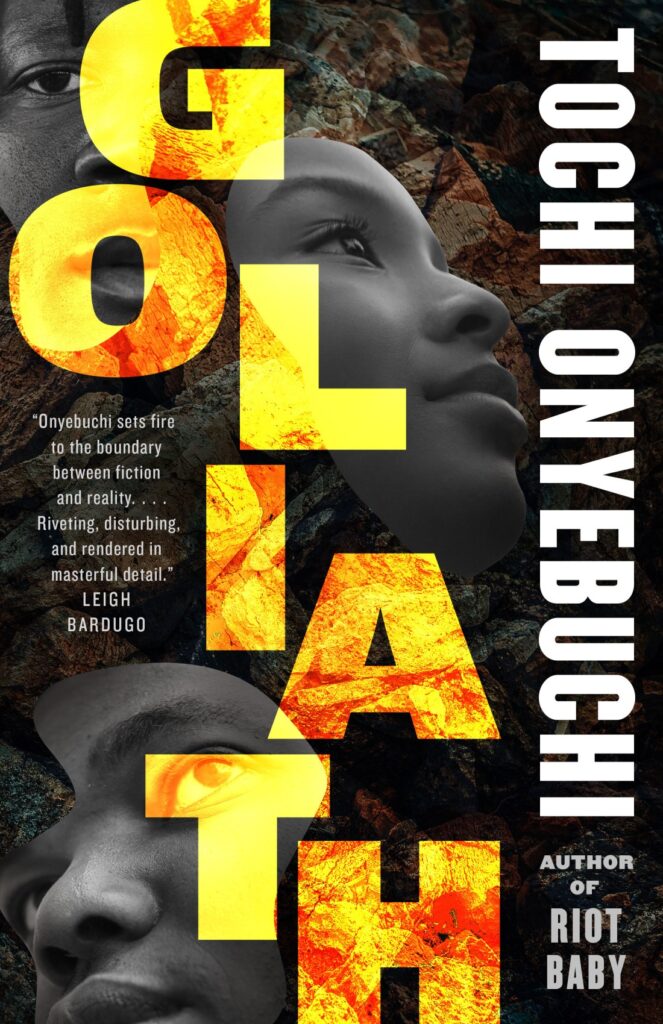

I mentioned Tochi Onyebuchi’s Goliath in my Hugo ballot post, and reviewed it on my blog. But the further I get away from it, the more convinced I become that this is one of the major science fiction novels of 2022, and that neither I nor the fandom as a whole have done enough to promote or discuss it. I was therefore thrilled when Strange Horizons reviews editor Dan Hartland proposed a roundtable discussion of the novel. Along with A.S. Lewis, Archita Mittra, and Jonah Sutton-Morse, it was a thrill to go deep into this remarkable, challenging book.

Goliath takes place in a climate-degraded future where much of the US is toxic, and the government has broken down (in some parts of the country, to be replaced by a resurgent neo-confederacy). Those who were able left for offworld stations, further degrading the services and support offered to those left behind, who are mostly non-white. With economic pressures mounting in space, some people have begun returning to Earth, gentrifying (or perhaps invading) the remaining human neighborhoods. The novel takes place among a group of “stackers”—people who disassemble buildings in order to send their raw materials into space—in New Haven, as they observe the arrival of a young couple from the colonies in their neighborhood, and the knock-on effect their presence has.

It’s a much looser, wider-ranging novel than that description implies, though, and our discussion was similarly wide-ranging, touching on Hobbes’s Leviathan, Black Marxism, the brouhaha over Ta-Nehisi Coates’s lack of optimism, Speculative Blackness, and many others.

Dan Hartland: I really appreciate how careful but also honest we’re being here. Chief among our breakthroughs so far might I think be this observation of A. S.’s that Goliath is seeking to achieve an alignment between the reader and the POC body: when Jonah observes that the novel chooses to focus on people in a moment, and asks us to dwell on that, or Archita makes what is for me a key argument about this novel—that its radicalism is in its insistence on empathy—they are both, I think, orbiting this idea that the novel is creating ways for us to cross gulfs. Science fiction creates worlds, but worlds are dependent—or perhaps shaped—by the people in them, the people allowed to be in them … and this means that science fiction can only build particular types of world until it finds ways of forging better connections between reader and read. For all its self-regard as a literature of ideas, science fiction has not always done this terribly well, to its cost.

But I think this also brings us to Abigail’s problem with this particular novel: that its generic expression feels somehow off. It’s “a science fiction novel whose attitude is so antithetical to the idea of change.” Why is Goliath even written as science fiction? If it’s an empathetic project, why could it not be a piece of literary fiction set in the present day? Or why not a fantasy, shorn of all the need to invent a future history? Heck, it more or less turns into a western at one point—why not commit to that mode? The science fictional element must have been selected for a reason, and I don’t think Abigail is wrong to pause over—be troubled by—this choice and how it might be destabilised by, or in turn destabilise, the novel’s project.

That said, I might turn to Darko Suvin, who famously characterised SF as the literature uniquely equipped to “estrange the author’s and reader’s own empirical environment” (in Metamorphoses of Science Fiction [1979]). Is this not what Goliath is doing—estranging our understanding of race and racial politics, of ourselves, to force us to think more clearly and expansively about people and life experience? In this, you might even want to argue that the novel is science fictional in intent rather than content (though surely this would be to take it too far, given this is a book with a space station in it).

So … can we sit with the novel as science fiction for a bit? It offers us both spaceships and machines that suck up houses, and post-plenty horses and dust bowl migrants. Obviously, and as Abigail has already said, to some extent Goliath is simply another iteration of the unevenly distributed future, which has come to be the default mode of a lot of contemporary SF. Does it do anything new with its generic elements? Or are they here mostly as a means of delivering its effect of transposition into the POC experience, of transliteration of structural racism? How central is SF to the novel’s success?

Abigail Nussbaum: Well, on the most trivial level, Goliath is science fiction because Onyebuchi is a science fiction writer. That’s the idiom he works within and is comfortable with. (And it’s the part of the publishing industry where he has relationships and can pitch a novel to a receptive audience who know him and what he’s capable of, as opposed to starting on the ground floor with a mainstream publisher.)

But I also wonder if the SFnal angle isn’t necessary for a book like Goliath to get published, get read, and get attention. If it had just been a naturalistic novel about gentrification and police brutality, would it have been considered as publishable? Would readers (and especially white readers) have been attracted to it, or would it have been dismissed as too challenging and bleak? Actually, this is a fate that I think it has suffered from anyway—I can think of no other explanation for its absence from, for example, the Nebula shortlist.

Indeed, I’m more than a little saddened by how little awards attention this novel has received (I guess we don’t yet know if it’s going to be nominated for the Hugo, but I’m not holding my breath). Goliath seems to me like one of the major genre novels of last year—however you define that genre—and I don’t think that has been appropriately recognized. It’s hard not to feel that this is down to readers finding the book too challenging, or too depressing, or maybe not even picking it up because it was about race.

I’m thinking of the way The Underground Railroad needed to couch its story in fantastical terms, not so much in order to soothe readers, as to give them a hook and point of interest, whereas a straight depiction of slavery and escape from it might have struggled to attract an audience.

Archita Mittra: Which I think brings us back to Dan’s next question of, why SF? I agree with Abigail’s doubts about the novel being as publishable if it was written in a naturalistic form. I personally think that, had Onyebuchi opted for a literary fiction form, or journalistic/academic non-fiction, the story would still work, but the readership would be (comparatively) different. I mean, this is just my experience (and I might be wrong), but I think the other two forms could attract a possibly niche and “posh” (?) audience, and it may not have been seen as “accessible” (?) in the way a genre fiction novel is marketed to be—so the conversations around it could be tantamount to the very “seminar on white privilege” that the book scoffs at, instead of being more diverse.

Again given the choice of publisher, the book is possibly aimed at an American readership, including both white and POC reader. I am fairly sure I’d never find a physical copy of this book in an Indian bookstore, and I actually checked the Amazon prices of the hardcover/paperback in Indian currency—they are priced similarly and too high, charge a delivery fee, and indicate almost a month-long delivery date, so not exactly accessible/affordable for SFF fans here, unless they opt for the Kindle ecopy. But none of this is the author’s fault. Rather, it is the way western publishing in the English language decides who to market what books to, and how publishing rights and editions are distributed across countries, I suppose. So even if the core themes resonate with people from all over the world, the central concerns of the book are aimed at the inequalities manifest in American society in particular. I think the SF tag makes the novel more accessible, and while it may not be doing anything new with generic elements, it utilizes it for the translation into the POC experience in a way that feels immersive and real, on a very raw and visceral level.

This roundtable is being published as a funding milestone in Strange Horizons‘s annual fundraiser. Though the base funding level has been reached, there are still several stretch goals to go, including raising contributor pay and funding themed special issues. I think this roundtable really sums up Strange Horizons‘s specialness—there aren’t a lot of venues for SFF criticism that would not only spend time on a year-old novel, but bring together a large group of people for an in-depth discussion about it. If you’re able to, I hope you’ll consider giving the magazine your support.