This Day in Labor History: October 12, 1962

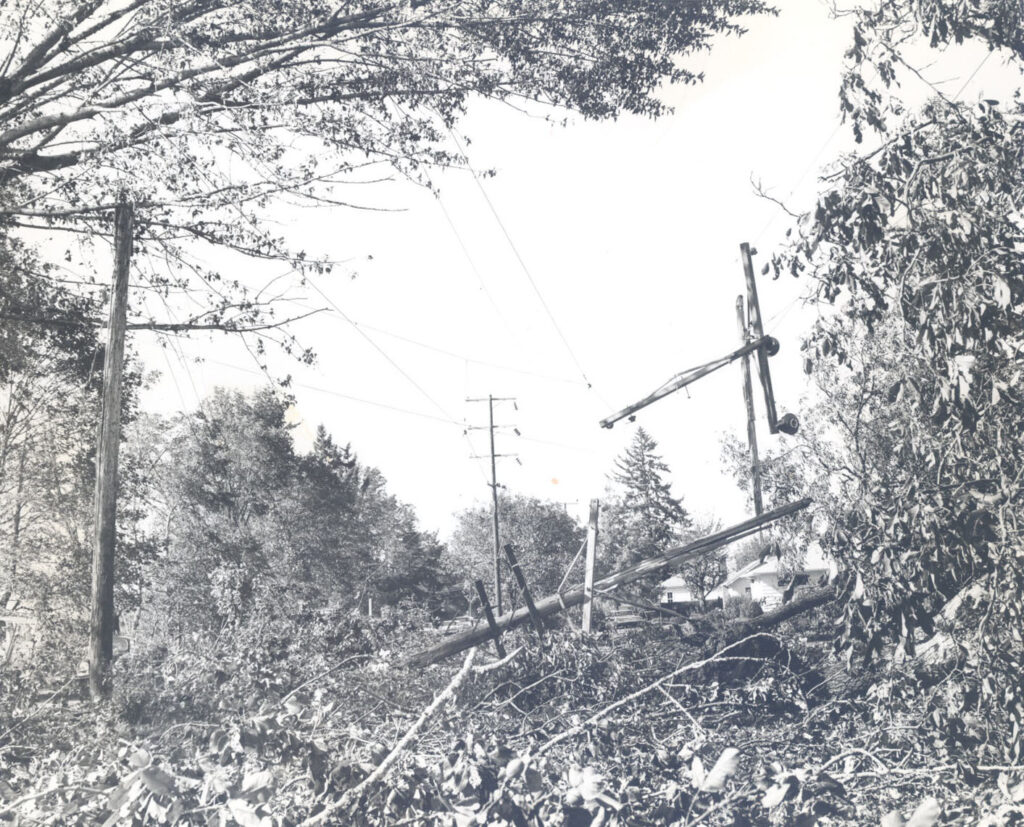

On October 12, 1962, a powerful storm, a former typhoon that was now a post-tropical storm, came ashore in western Washington and Vancouver Island in Canada. Its size and power was felt well into Oregon as well. This storm blew over millions of board feet of timber from trees on their way to being logged. This event, seemingly unrelated to our labor history, combined with American foreign policy desires and corporate greed in order to transform the timber industry of the Northwest and lay off thousands of workers.

The 1962 Columbus Day storm in Oregon and Washington toppled over 11 billion board feet of timber, far more than the American market could use. The federal government encouraged the sale of that timber to its Asian allies and a profitable market emerged. By the 1970s, sixteen percent of Northwestern log production went to the export market. A huge American market for timber was in Japan. The Japanese do have forests, but not nearly enough to harvest in order to supply its needs. But Japan had a different set of requirements and preferences for building than the U.S. What this meant is that American mills were required to adapt to Japanese standards. But what if we just shipped the logs unprocessed to Japan? The companies could close their mills and make profit on the direct logging trade.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government through the years of the Cold War consistently favored the needs of its allies over that of its unionized workers. As Judith Stein showed in her books about US export policy, especially around steel, the government knew that moving steel production from Ohio to Japan or Korea or Taiwan would hurt American unions, but it would help extend American power overseas. They made this decision over and over and over again, both Democrats and Republicans. In the end, unions were never a high priority for any American government. The aftermath of this storm is another example in a less famous industry in this country.

Unions were furious. The International Woodworkers of America worked hard to resist log exports. In 1964 IWA mills in Port Angeles demanded the international fight exporting logs after a mill laid off union members for a lack of logs while ships departed the port laden with logs headed for Japan. By the next year, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters estimated 1,000 unemployed timber workers from raw log exports and both unions officially registered their opposition. Pressure from the Washington and Oregon congressional delegations convinced the Johnson Administration to negotiate a quota on exports from public lands in 1967. The Morse Amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1968 went further, limiting log exports from federal land to 350 million board feet per year and in 1974, the government prohibited the export of softwood logs from federal lands in the West.

While unions and congressmen could pressure the federal government for change, the states proved trickier and private owners intractable. A 1968 attempt to ban export of timber from Washington state lands lost at the polls and the state had no meaningful restrictions until 1990. Oregon did restrict exports from the early 1960s but stopped enforcing the laws in the 1980s, leading to a rapid increase in the state’s timber sold to Asia. Private timber had no restrictions. Sending 800 empty lunch buckets to Washington, in 1974 the Carpenters demanded that President Ford cease all exports of raw logs, claiming this alone would allow the timber industry “to return to full employment within a few weeks.” In 1977, the IWA estimated that processing timber in the U.S. for the Asian market would create 11,000 jobs.

The IWA connected log exports to sustainable forestry practices. When the Carter Administration proposed increasing exports, Keith Johnson wrote to the president that the union worried about undermining the long-term forest sustainability, noting USFS studies projected a 24% decline in timber harvests from the national forests by 2000. Instead, keeping wood for the American market by restricting the exports of raw logs would both reduce the price of wood and maintain a healthy, productive forest. For an IWA suffering 2000 job losses from seven mill closures in 1980, exporting logs while increasing harvests made neither ecological nor economic sense.

Exports exploded during the Reagan years, peaking in 1989 at 1.944 billion board feet of timber, twice of their peak during the Carter administration. Between 1979 and 1989, lumber production in the Northwest increased by 11 percent while employment dropped by 24,500 jobs. Liberal congressman from the Northwest like Oregon’s Jim Weaver and California’s Don Bonker introduced bills to limit exports, but powerful timber-friendly senators such as Oregon’s Mark Hatfield and strident corporate resistance ensured they went nowhere.

Thanks to mechanization and log exports, the number of people laboring in the timber industry had plummeted, even as the Pacific Northwest enjoyed robust economic growth through the 1980s. Whereas timber worker employment in Washington and Oregon fell by nearly 25,000 workers in the 1980s, total employment in the two states grew by 625,000 jobs and many new residents had a different stake in the forests than loggers. The timber industry’s political power was decreasing as the Northwest became more urban and politically liberal. The economic value of the forests increasingly came in trees standing than trees logged. When residents organized to fight the timber industry for the last ancient forests in the 1970s and 1980s, timber workers feared for their jobs and timber worker unions would be a rapidly declining shell of their previous incarnations.

Of course as all this was happening, environmentalists were seeking to save the northern spotted owl. The timber industry opposed this but used it to deflect blame from its log export practices. Environmentalists tried to take advantage. Even in these days of bitter struggle, timber unions and environmentalists could agree on the damage caused by log exports. Exports increased forty percent during the 1980s, from 2.6 billion board feet in 1980 to 3.7 billion board feet in 1989. For environmentalists, attacking exports was central to their strategy of showing their concern for the Northwest’s economic future. The Wilderness Society repeatedly stressed that ancient forest protection could protect both ancient forests and jobs.

Oregon congressman Peter DeFazio finally shepherded a 1990 law prohibiting exporting raw logs from federal lands, a rare victory for timber unions during these years. IWA president Wilson Hubbell said the law “will increase the job security of every woodworker in the U.S.” But regulating logs from state or private lands seemed impossible. When the Wilderness Society reached out to the Carpenters to form a more united front on exports, the UBC rejected it because “Congress, in our view, is not ready to restrict the use of private property.”

When DeFazio pressed for a bill that would tax private timber exports in 1991, the IWA and UBC supported it, but the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), whose workers loaded raw logs onto the ships, angrily opposed it. ILWU Local 24 president Glen Ramiskey lambasted DeFazio “for pitting worker against worker.” Congress rejected the bill as it turned toward promoting free trade policies. Banning log exports would not be a solution to the job problems of the Northwest woods.

The shorter version of this is that the government was fine letting companies undermine unions to promote the Japanese mill industry and that unions themselves were divided by politics in their response. The IWA was more aggressive to industry. The Carpenters were more concerned with defending capitalism than standing up for its own members. And the Longshoremen were simply happy to have more jobs and didn’t care if other workers were undermined by that.

This is how a natural event can intersect with a lot of other issues to transform an entire region and industry’s history.

I borrowed from my book Empire of Timber: Labor Unions and the Pacific Northwest Forests for this post.

This is the 579th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.