Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,940

This is the grave of Charles Russell.

Born in 1864 in St. Louis, Charles Russell was in love with the American West and its mythology at the very time it was being created. The thing to understand about the West and the romance around it is that at the very same moment that the genocide was clearing the land for white settlement, people were writing about its greatness and its loss. Capitalism was soon to replace it with enormous railroad holdings that moved into cattle and timber and mining operations. Most of these would be hard to romanticize. But not cowboying. That seemed to combine the romance of the Old West with the economy of the New West in that it was Man Against Nature. This is part of the background one needs to understand the life and work of Charlie Russell.

At the time Russell was a small boy, there were still a few fur traders around and he loved to see them. He wanted to explore the West as well. So he did so by learning to rope and ride and then, in 1880, moving to Montana to work on a sheep ranch. Now, sheepherding wasn’t exactly the fur trade. But Russell worked as a sheepherder and a cowboy for the next several years. He also loved to draw and paint. In the terrible winter of 1886-87, when the millions of cows placed on the Plains in an economic boom funded by New York and British investors enamored with the same bullshit myths that moved Russell (including Theodore Roosevelt) all froze to death, the owner of the ranch where Russell worked wrote from wherever he was (definitely not Montana) to see how bad things were. The foreman replied with a postcard painted by Russell of the devastation. The owner wondered who this kid was, the postcard eventually ended up in a shop in Helena, and people started wanting to see more art of the cowboy life painted by Russell.

Russell began painting more frequently and selling his works shortly after this. Then came a period of his life somewhat enshrouded in myth, which is that he evidently spent a lot of time with the Blackfeet, Now, Russell would become a political advocate for Native American lands when he became famous, but that only goes up to a point, in that he was very much romanticizing their disappearance. Those behind the Russell myth talk about how he was brothers with the Blackfeet and basically a tribal member and….well, those claims should be taken with an entire salt lick. But he did spent a good deal of time on Blackfeet land in 1888 and 1889.

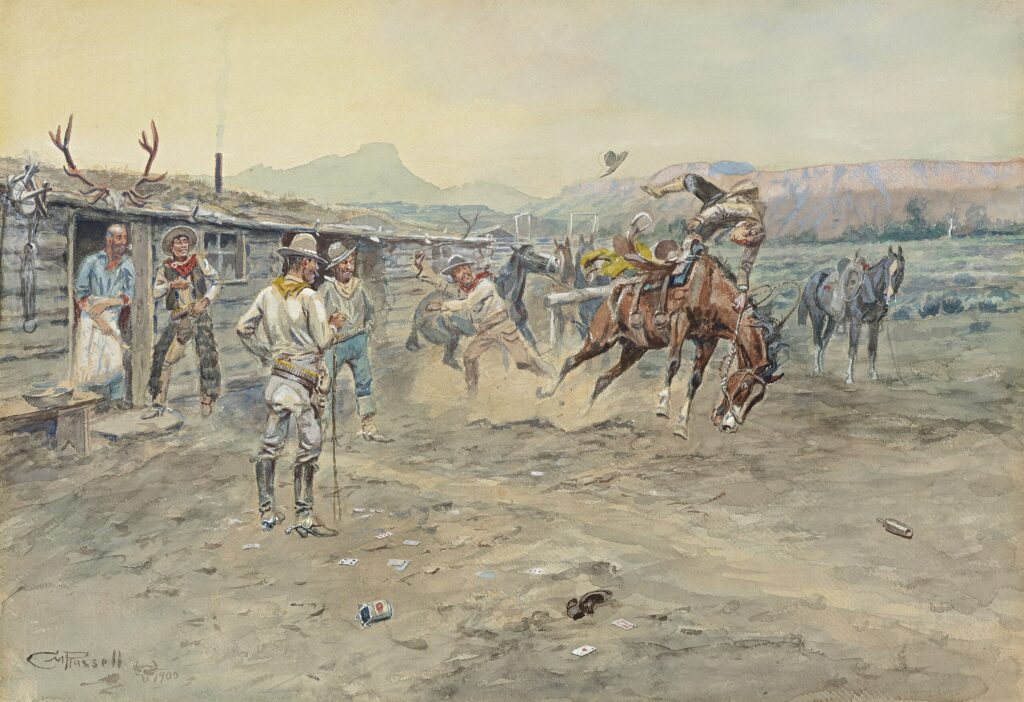

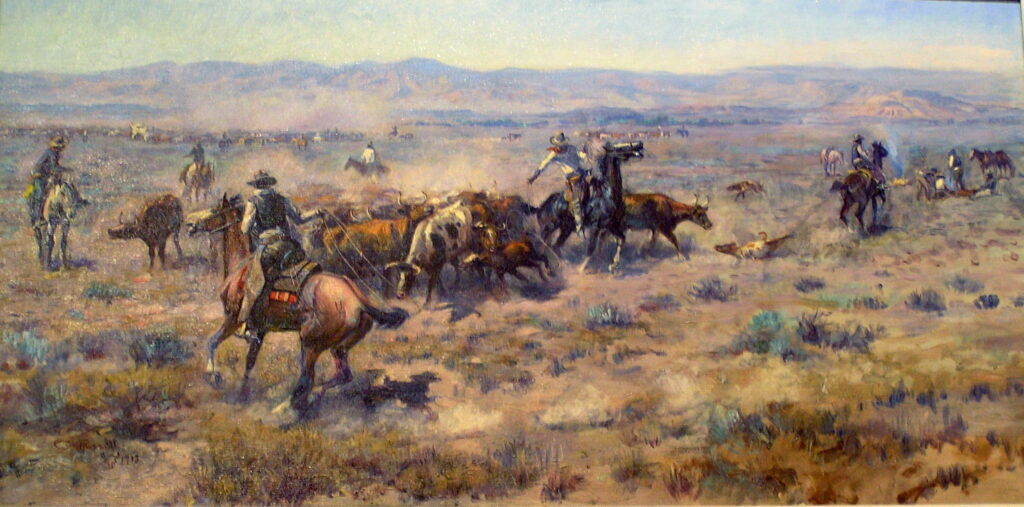

Also in 1889, Russell decided to give up cowboying, which was not exactly a job for the older man, and live in Great Falls, Montana, where he would paint full time. He married a young woman, only 18 years old, in 1896. Nancy became the great marketer and promoter of his work. Russell painted and painted and painted. He basically created the modern genre of western art. The unfortunate part about this is that it is almost all terrible–artistically basic and with nostalgia absolutely at its core. At least Russell knew these guys, even if this was mostly true of him too. But the stuff in the century since his death…..woof. But if you want to get ripped off in Santa Fe art markets, be my guest.

Russell was prodigious. It’s not like this was that hard to paint really. He has somewhere in the nature of 4,000 paintings that still exist, plus some sculpture of cowboys and horses and such.

A bit more is in order on Russell’s Native American connections. To his credit, he did advocate for the Chippewa, who were from nowhere near Montana, to get a reservation there because they had no reservation at all. So a small piece of land, the Rocky Boy Reservation, was created in north-central Montana in 1916. And while Russell certainly did reflect the white dominance of the time, one thing he did do in his art–however you want to consider its real artistic merit–is paint these history paintings of the past from what he saw as a Native perspective, as opposed to just a white perspective. So he has a bunch of Lewis & Clark Expedition paintings, imagining those scenes in the places where they took place, near where he lived in Montana, as well as farther west, which he didn’t know as well. Of course they aren’t very realistic, but at least they weren’t all from the white perspective. Some really did try to imagine it from the Indian side of things. Again, a man of that time and place is inherently going to have limitations here, but at least there was some effort.

What can’t be denied however is how much western whites loved Charlie Russell. Still do as well. The state of Montana hired him to paint a mural in the state House chambers. It is 1912’s Lewis and Clark Meeting Indians at Ross’ Hole. The art world in the American West is seriously divided today between museums showing actual art with some connection to the broader art world and museums that are dedicated to Old West art and its modern purveyors of it. So you aren’t going to find much if anything from Russell at the DeYoung or the Seattle Museum of Art. But the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth? Or the Buffalo Bill Center in Cody, Wyoming? Just pour it on. Dozens of these pictures will be on display for your pleasure, or dismay as the case may be. The type of guy who watches Yellowstone and decides that he is going to build a $125 million estate in Montana or Jackson Hole is going to festoon it with Russell and his descendants. Piegans, a 1918 painting, for instance, sold for $5.6 million back in 2005.

But that didn’t start after his death. Russell was able to enjoy the first generation of rich guys wanting to be westerners. Among other things, he became buddies with the first Hollywood cowboys and adventure actors, such as William S. Hart and Douglas Fairbanks, not to mention Will Rogers. These men saw Russell as a man of the actual Old West that could impart those lessons of them. He was happy to do so in his older age. Russell died in 1926. He was 62 years old. Heart attack got him. The city of Great Falls gave children a day off from school so they could attend his funeral.

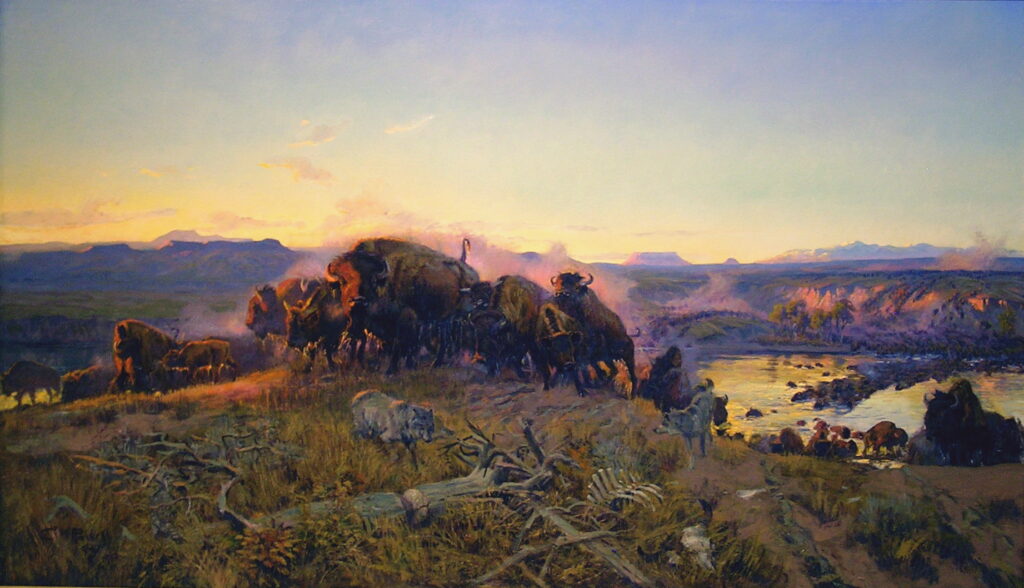

Let’s look at a few Russell paintings, so you can see what you think. As you can tell, I kind of roll my eyes at it al.

Charles Russell is buried in Highland Cemetery, Great Falls, Montana.

If you would like this series to visit other western artists, which will probably be even more negative than this post, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Harold Dow Bugbee is in Clarendon, Texas and J.K. Ralston is in Billings, Montana. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.