Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 2,083

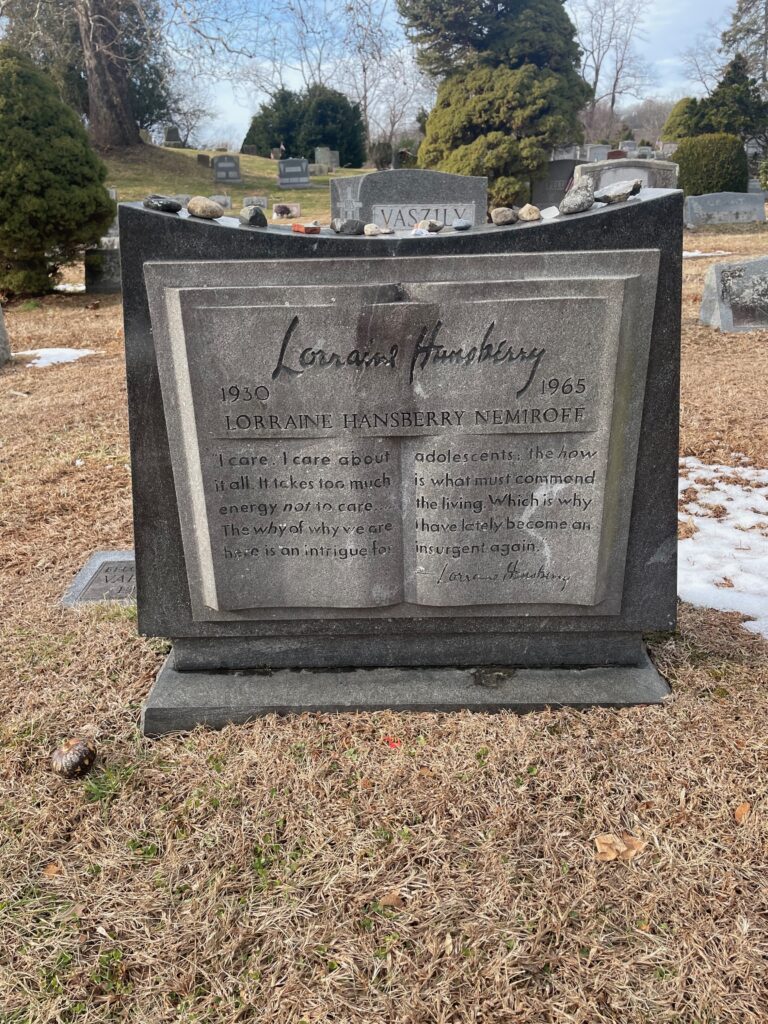

This is the grave of Lorraine Hansberry.

Born in 1930 in Chicago, Hansberry grew up in the upper middle class part of the Black community in that city. Her father made a ton of money in real estate. In 1938, they desegregated a white neighborhood, which was a physically risky thing to do. The way this usually worked was that someone would sell a house to a Black family, often because they didn’t care who they sold to and sometimes because they thought integration was good anyway. The locals would be outraged and commit violence and then they would all put their houses up for sale and move to some other cracker land. In this case though, there was a restrictive covenant involved. Hansberry’s father sued and it went all the way to the Supreme Court in 1940. In Hansberry v. Lee, the court decided 6-3 more or less in favor of Hansberry. It didn’t totally strike down restrictive covenants, but it laid the groundwork for Shelley v. Kraemer, which did do that, in 1948.

With that kind of badass background, big things were expected of young Lorraine. She delivered on those expectations. It didn’t hurt that they were friends with everyone–W.E.B. DuBois, Jesse Owens, Duke Ellington, Paul Robeson. Lorraine went to the University of Wisconsin. She became a member of the Communist Party. Her father was a Republican and of course a real estate guy and I wonder how that would have gone, but he had died in 1946 of a heart attack. She was big on the Henry Wallace campaign in 1948 and then did some art training in Guadalajara, embracing the art and social scene in Mexico at a time when it was still pretty welcoming to leftists and artists.

By 1951, Hansberry had moved to New York to get involved in both politics and art. She became enmeshed in the Harlem scene, which perhaps wasn’t quite as groundbreaking in terms of importance as the peak of the Harlem Renaissance 25 years earlier, but was still a critically important site of Black American cultural production. She got to know almost everyone immediately, including all-time legends such as Robeson and DuBois. She worked on Freedom, the important Black paper of the early 50s that brought a lot of discussion of the anti-colonialist struggles into the greater interest readers had in what was going on in the U.S. She started just as a typist but eventually became associate editor.

Shortly after getting to New York, Hansberry married a Jewish activist and songwriter named Robert Nemiroff, but in truth, she was a lesbian who was in the closet for most of her short life, as so many were in the 50s. They separated in 1957 and she started getting in touch with the lesbians in the Daughters of Bilitis, the important early homophile organization that laid so much groundwork for the modern gay rights movement, even if it was on terms that would make contemporary queer activists sometimes feel like they were sellouts (and to be honest, sometimes some of the more radical activists at the time felt that way too). She even started writing–very tentatively–for their magazine, using initials only and just a couple of letters. But she and Nemiroff remained close, even as she slowly moved toward coming out. It didn’t hurt that he wrote a huge hit pop song called “Cindy Oh Cindy,” which was adapted from a Sea Islands folk song and which The Weavers and then The Kingston Trio went big with. So the money from that basically allowed her to write full time without working. They would eventually divorce in 1962, but remained close friends.

Of course, what Hansberry is truly known for today is her 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun, one of the most important plays ever written in this country. She reached back to her Chicago roots for the play about a family whose father died and who will get an insurance payout but then also facing that even money can’t overcome the structural racism faced by Black Americans, particularly in buying a home in a white neighborhood. The play, with its all-Black cast except for one character, had many of the biggest stars of the day in it, most notably Sidney Poitier in the lead, but also Ivan Dixon, Ruby Dee, and Louis Gossett, Jr. After Poitier left the production for other work, Ossie Davis took over the part. This was the first play written by a Black woman to be produced on Broadway. On Opening Night, Hansberry did not want to accept the cheers and accolades the audience provided and so Poitier basically pulled her onto the stage to accept her due. Hansberry also wrote the screenplay for the film version, which of course wasn’t that different.

The success of Raisin in the Sun did forestall much more work happening, though eventually it probably would have. She worked on things, of course. But the only other play she got through to completion and staging in her lifetime was 1962’s The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which was about a Jewish artist in New York in a bad marriage. I don’t think it was really based on her marriage though. The play was not particularly well-received though. I do wonder how much of that is that reviewers wanted her to focus on the Black experience and not write a play about Jews, a sort of authenticity argument I am sure was part of the story. It got staged in 1964 and by this time, Hansberry was really sick. Gabriell Dell and Rita Moreno were the stars.

Up to the end, Hansberry worked on politics as much as literature. Like many in her generation, she was deeply committed not only to the civil rights cause at home but the anti-colonial cause in Africa. The term “internal colonialism” does such a great job of placing the Black Freedom Struggle in the U.S. in this proper context of global anti-colonialism. James Baldwin set up a meeting with her and Robert Kennedy to push the Kennedy administration on civil rights, which it wasn’t very good at and to the end of her all too short days, she wrote and fought for justice on a global scale.

One of the great tragedies of American letters and really just of America generally is Hansberry developing pancreatic cancer at such a young age. She died in 1965, at the age of 34. One of the biggest “what could have been”s ever. Even outside of her writing, she would have contributed so much to the feminist and gay rights movements as she likely would have been more comfortable on those issues as they became more mainstream.

Lorraine Hansberry is buried in Bethel Cemetery, Croton-on-Hudson, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other American playwrights, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Neil Simon is in Pound Ridge, New York and August Wilson is in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.