Follow the rules or do the right thing?

I had an email exchange a few days ago with Andrew Gelman about something he wrote a few years ago about how universities are run, which he reproduced in a post yesterday. The post is about the much broader question of what it means for bureaucracies — governments, universities, corporations, etc. — to follow their own rules, as opposed to simply allowing their executive branches to do whatever seems best at the moment. (The latter option is essentially what John Roberts and the Furious Five’s Unitary Executive rap is all about).

From Gelman’s older post:

Academic and corporate environments are characterized by an executive function with weak to zero legislative or judicial functions. That is, decisions are made based on consequences, with very few rules. Yes, we have lots of little rules and red tape, but no real rules telling the executives what to do.

Evaluating every decision based on consequences seems like it could be a good idea, but it leads to situations where wrongdoers are left in place, as in any given situation it seems like too much trouble to deal with the problem.

An analogy might be with the famous probability-matching problem. Suppose someone gives shuffles a deck with 100 cards, 70 red and 30 black, and then starts pulling out cards, one at a time, asking you to guess. You’ll maximize your expected number of correct answers by simply guessing Red, Red, Red, Red, Red, etc. In each case, that’s the right guess, but put it together and your guesses are not representative. Similarly, if for each scandal the university makes the locally optimal decision to do nothing, the result is that nothing is ever done.

This analogy is not perfect: I’m not recommending that the university sanction 30% of its profs at random–for one thing, that could be me! But it demonstrates the point that a series of individually reasonable decisions can be unreasonable in aggregate.

Anyway, one advantage of a judicial branch–or, more generally, a fact-finding institution that is separate from enforcement and policymaking–is that its members can feel free to look for truth, damn the consequences, because that’s their role.

So, instead of the university weighing the negatives of having an barely-repentant plagiarist on faculty or having the embarrassment of sanctioning a tenured professor, there can be an independent committee of the American History Association just judging the evidence.

It’s a lot easier to judge the evidence if you don’t have direct responsibility for what will be done by the evidence. Or, to put it another way, it’s easier to be a judge if you don’t also have to play the roles of jury and executioner.

My comment to him about this was:

The answer to this supposedly is that universities now all have compliance offices of some sort when it comes to non-academic scandals, and internal mechanisms when it comes to academic ones. But if faculty governance is weak to non-existent these mechanisms are just captured by the administration. Kind of like the US government at present.

Gelman then considers the subject within the larger frame of how legal regimes are supposed to work, and he offers the following schematic:

The standard characterization of the legal system, as I understand it, is that it balances on three stools:

(1) Structural ideas (fairness, stability, and various conceptions of the public good);

(2) Rule-following or, more generally, a paper trail or justification for any ruling; and

(3) Consequentialism (that is, good outcomes).The “balls and strikes” model of judging would just use principle 2, but that won’t work, partly because rules always have some vagueness and need to be interpreted based on general principles, and partly because outcomes matter.

The “philosopher king” model of judging would just use principle 1, but that won’t work either, partly because general principles can conflict with each other and partly because different judges will interpret them differently, hence the need for some rule-following in service of some general principle of stable laws.

The “unitary executive model” (i.e., what we have at universities and corporations) just uses principle 3, but that has problems too. For one thing this creates perverse incentives (an implicit license to violate the law if it would be too costly for the government to enforce it), leading to an accretion of lawbreakers. Consequentialism also has the problem that you need to consider immediate consequences, medium-term consequences, long-term consequences, . . . there is no end. Having clear laws (principle 2) cuts that Gordian knot.

Another way of looking at this is to say that a key function of a law-based system is not just that the laws guide judges and tell people what to do, but also that the laws provide a sort of retroactive justification of consequentialist decisions.

This in turn leads him to consider how such a scheme can be understood in the light of various decision analysis theories:

This is related to the the point that decision analysis can be done in a “forward” or “reverse” fashion. In forward analysis, you state all your assumptions clearly and then evaluate the decision tree and pick the optimal decision. In reverse analysis, you apply forward analysis under a range of assumptions, and then if the recommended decision is not the decision you want to take, you go through step by step and figure out where your assumptions are wrong.

This bidirectional nature of decision-analytic reasoning is a fundamental part of classical Neumann-Morgenstern utility theory: in the forward direction, you can use utility analysis to make decisions; in the reverse direction, you can use decisions to deduce the utility function. In practice, we go back and forth: we make assumptions about probabilities and utilities in order to derive decisions, we look at patterns of decisions to infer probabilities and utilities, and when we find incoherence in our explicit or implicit patterns of decisions, we reflect on where our assumptions went wrong, and we modify our models accordingly.

That seems right to me, to the extent I understand it, although the rest of Gelman’s discussion is quite technical and I can’t really follow it (some of you will undoubtedly understand it better than I do).

What I’m going to do in the rest of this post is take Gelman’s description of how law works or is supposed to work as a decisional system, and consider it within the context of a specific legal issue in the American legal system.

I believe Gelman’s frame for interpreting legal decisions is basically correct, although I would characterize it a bit differently, as follows:

Legal decision makers — let’s just consider judges for simplicity’s sake — can either follow the formal rules, or do the right thing, when there’s a conflict between the former and the latter. Gelman’s philosopher-king model (1) is made up of the meta-rules within the system for deciding when judges ought to follow the rules (2), or do the right thing (3). This can be seen most readily by considering the doctrine of stare decisis, which is a meta-rule that says stability in a legal system is more important than fairness in the individual case, except when it’s not. Less facetiously, stare decisis in the context of for example constitutional interpretation in the American legal system is the principle that the SCOTUS shouldn’t function as a kind of super-legislature — that is, a decisional body that overrides (2), aka the pre-existing formal rules, in favor of (3), aka doing the right thing, except when the pre-existing formal rules generate such a bad outcome, consequentially speaking, that fairness in this particular circumstances should trump systemic stability.

Now originalism as a constitutional theory of interpretation is based on the claim that, in constitutional adjudication, doing the right thing should NEVER trump following the pre-existing rules. A logician would notice that, taken seriously, this view entails that the doctrine of stare decisis, which is part of (1), is itself unconstitutional, but as somebody or the other once said the life of the law has not been logic but experience.

Let’s turn to a specific case, or pair of cases, to see these arguments playing out in practice.

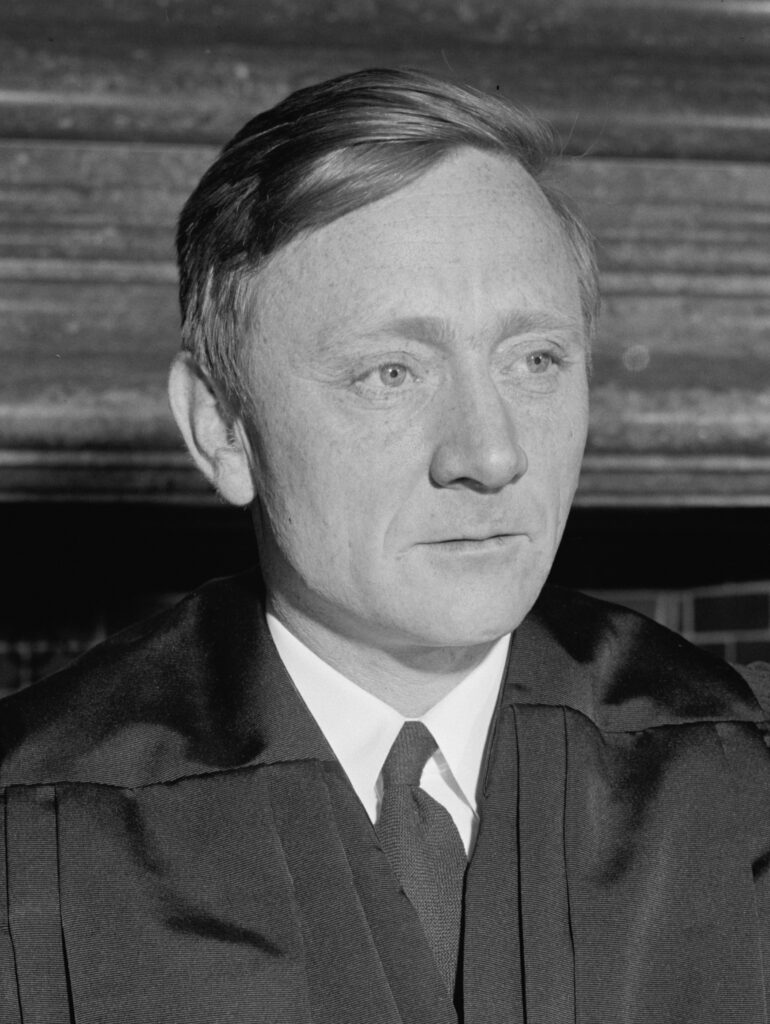

60 years ago, the SCOTUS declared in Griswold v. Connecticut that state laws criminalizing the purchase of contraceptives by married couples were unconstitutional. As many a Federalist Society denizen has ranted (quite accurately by the way), it would be generous to call William O Douglas’s opinion for the Court slapdash. Douglas wrote or at least signed the Griswold opinion when he was entering the DGAF period of his constitutional jurisprudence, and, from a formalist perspective, the opinion is a laughably transparent exercise in overt question-begging. The real holding in the case is that seven of the nine members of the SCOTUS thought the law in question was a ludicrous and grotesque exercise in governmental policing of sexual relations between married people. In other words, they thought it was a Very Bad Law — so bad, in fact, that they functioned as an effective super-legislature to get rid of it. Douglas’s opinion tries to retcon this sentiment into an “interpretation” of “the Constitution,” but this is the kind of metaphysical nonsense that in my experience only law professors take seriously, and not all of them by a long shot.

Now, should the Supreme Court do this kind of thing? Originalists say absolutely not, although things get tricky once the SCOTUS has done it, because a meta-rule of the system is that the SCOTUS shouldn’t reverse its holdings unless the holding is a Very Bad Law itself to the point that it ought to be reversed. But why do they say that? The dumb ones say “because the Constitution doesn’t make the SCOTUS a super-legislature,” without noticing that this conclusion is itself both pure question-begging — the whole question here being “what does it mean to properly ‘interpret’ the ‘Constituiton'” — and, even if it weren’t, would still be a purely political position. After all, why should judges follow the original meaning of the Constitution instead of doing something else? The Constitution itself contains no rules on how to interpret it, and even if it did those rules would be subject to a meta-interpretive political question of how those rules themselves ought to be interpreted. So originalism does exactly nothing. to remove courts from making political as opposed to purely formal legal positions, which is supposed to be the whole justification for originalism.

Which brings us back to Gelman’s frame. Griswold is a case in which seven of nine SCOTUS justices decided to interpret the meta-rules of legal interpretation (1) in his frame), to Do the Right Thing (3) in his frame), instead of following the pre-existing formal rules (2) in his frame). You can say, as our Federalist Society ranters do, that that’s a bad thing to do, but that’s not actually an argument, it’s just a conclusion in the guise of one.

In this light I’ve always found it interesting that Griswold, which is even more shoddily reasoned than Roe, was basically a completely non-controversial decision at the time, in that as a political matter nobody really cared enough about it to try to do anything about it, no doubt because with the exception of a few integralist Catholic wack jobs (hi Adrian) everybody pretty much agreed with the substantive conclusion that such laws were Very Bad Laws, and didn’t care that Douglas’s formalist argument was about as convincing as a book-length argument that Donald Trump is actually a devout Christian if you squint just right. Griswold has subsequently become controversial because Blackmun used it in Roe* for his own transparently ludicrous formalist arguments, and I don’t doubt that one reason the SCOTUS did what it did in Roe is that Griswold generated practically no pushback eight years earlier, and it must have come as a shock to those clueless old men that Roe would end up getting a far different reception.

The larger point here is that all real legal arguments boil down to whether one should Follow the Rules or Do the Right Thing, and that arguments about interpretation are really arguments about interpreting the meta-rules for deciding whether one ought to do one or the other in the context of any particular case or controversy.

And the point about such arguments — arguments about for example whether and under what circumstances the SCOTUS should function as a crypto-Super Legislature — are political all the way down, and could not possibly be otherwise, because the very idea of non-political rules of legal interpretation is an oxymoron. It’s equivalent to arguing that politics should be done non-politically, although of course this is an argument that is made every day by our ubiquitous Reasonable, and Reasonably Reactionary, Centrists.

*Until 1968, nobody had ever suggested in print that abortion laws might be unconstitutional. The first person who did so was an Indiana University law professor who, three years earlier as a third year law student at NYU, had written a seminar paper about how the reasoning, such as it was, in Griswold could be used to make that argument. What inspired this particular seminar paper was the student’s struggles in helping his girlfriend get an abortion, which required a trip to Puerto Rico.