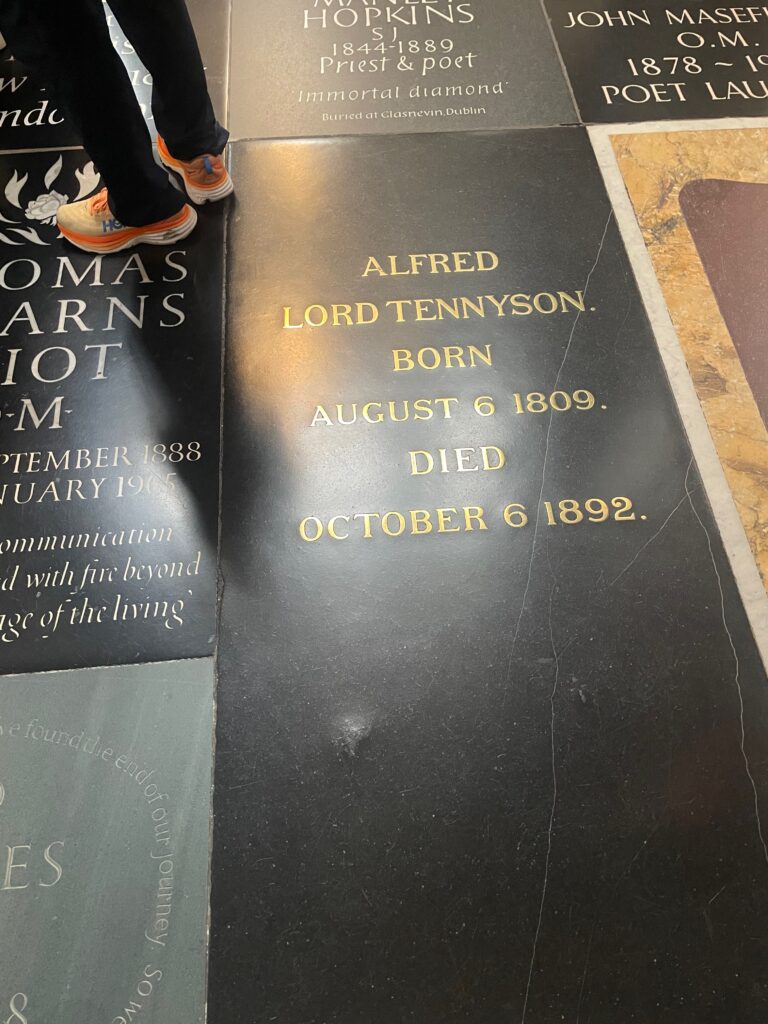

Erik Visits a Non-American Grave, Part 2,006

This is the grave of Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Born in 1809 in Somersby, Lincolnshire, England, Tennyson grew up firmly in the British upper middle class. Art was part of the family tradition and so Tennyson grew up reading a lot of Byron and other romantic poets of that nature. He went to good schools and then was off to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1827. He started writing poetry more seriously there and had his first book of poems published in 1830. He didn’t get the degree though, as his father died and he needed to go home and run the family operations. But he kept writing, publishing a second book of poetry in 1833. People hated it. I am not really sure why. But he didn’t publish again for nearly a decade. He was also pretty invested in the British political reforms of the 1830s and celebrated when the nation passed the Reform Act in 1832. His politics would remain in the liberal reform category for most of his life. He never would really trust revolutionaries, but he was also most certainly no Tory.

Tennyson married, had kids, and lost much of the family’s money in bad investments. But he was still writing poetry and got to know a lot of the other leading poets in London, including Thomas Carlyle, who encouraged him to publish again. So in 1842, he put out a new volume called Poems, a 2-volume set that combined reworked versions of some of his older works with a lot of new work. This hit pretty big. Now, to be fair, as a non-poetry reader, I don’t really know anything of Tennyson’s work, other than having heard of it. But this included many of what became his most famous poems, including “Ulysses” and “Locksley Hall.” His fame became even greater after publishing “The Princess” in 1847, a satire about women’s colleges which W.S. Gilbert later turned into both The Princess in 1870 and Princess Ida in 1884.

By the late 1840s, Tennyson was the most beloved poet in England. In 1850, he published “In Memoriam A.H.H.”, a poem in honor of his dead friend Arthur Henry Hallam, who had died very young of a cerebral hemorrhage. That year, he was named Britain’s Poet Laureate, which is a hell of a thing. Wordsworth had died. The first choice was Samuel Rogers, but for some reason he turned it down. So it went to Tennyson. Since he was still quite long, he would the official poet of Britain for a really long time. There were actual duties with this job too, so when visiting heads of state arrived for an official visit, Tennyson would write poems to honor them. He would also discuss the state of the day, which leads to what is perhaps his most known poem today (to be fair, this is what I know and anyone who reads this series seriously should I know that I am not an expert on poetry at all), “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” honoring the British soldiers who were unfortunate to be involved in that very bad battle in the Crimean War in 1854.

Interestingly, Tennyson resisted being made a lord and thus a peer for a very long time. Disraeli tried on multiple occasions to get him to accept one, but he continued to refuse. It was Gladstone who finally convinced him, in 1883. He kept writing until the end too, which was in 1892, at the age of 83.

Let’s read a Tennyson poem. Here’s “Ulysses”:

It little profits that an idle king,

By this still hearth, among these barren crags,

Match’d with an aged wife, I mete and dole

Unequal laws unto a savage race,

That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me.

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy’d

Greatly, have suffer’d greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when

Thro’ scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour’d of them all;

And drunk delight of battle with my peers,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy.

I am a part of all that I have met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro’

Gleams that untravell’d world whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnish’d, not to shine in use!

As tho’ to breathe were life! Life piled on life

Were all too little, and of one to me

Little remains: but every hour is saved

From that eternal silence, something more,

A bringer of new things; and vile it were

For some three suns to store and hoard myself,

And this gray spirit yearning in desire

To follow knowledge like a sinking star,

Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.

This is my son, mine own Telemachus,

To whom I leave the sceptre and the isle,—

Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfil

This labour, by slow prudence to make mild

A rugged people, and thro’ soft degrees

Subdue them to the useful and the good.

Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere

Of common duties, decent not to fail

In offices of tenderness, and pay

Meet adoration to my household gods,

When I am gone. He works his work, I mine.

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil’d, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

‘T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Alfred Lord Tennyson is buried in Westminster Abbey, London, England.

If you would like this series to visit American poets, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Henry Howard Brownell is in East Hartford, Connecticut and Alice Cary is in Brooklyn. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.