Erik Visits an Non-American Grave, Part 1,970

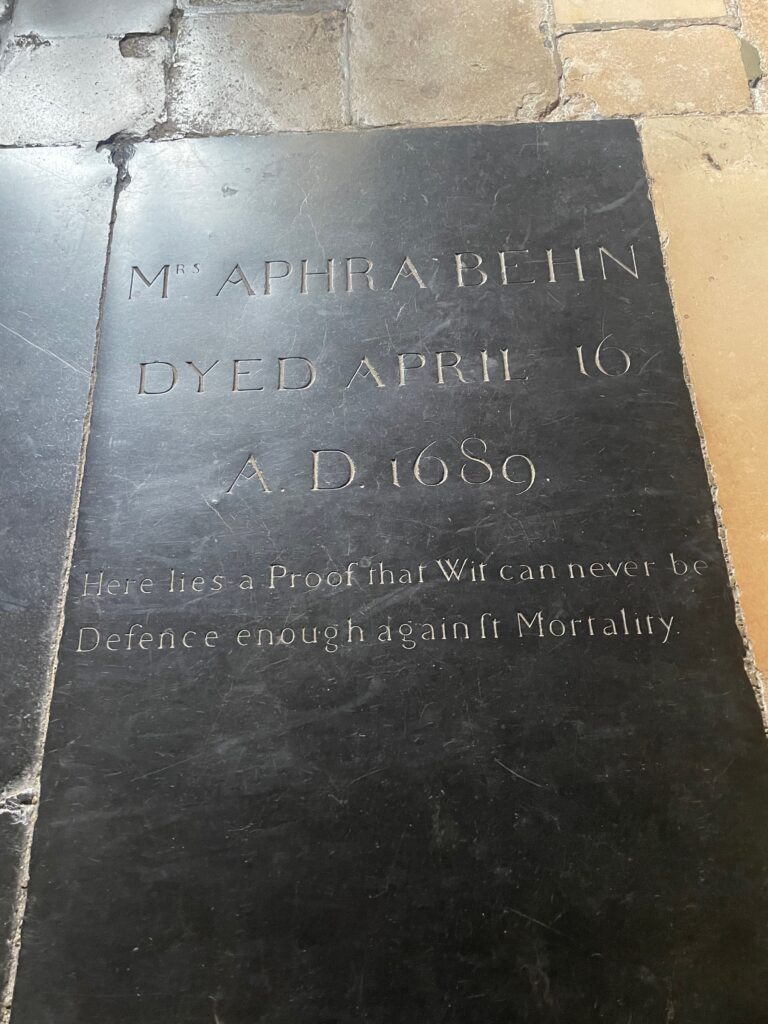

This is the grave of Aphra Behn.

Born in 1640 in Canterbury, Kent, England, we know almost nothing about Behn’s childhood, including her pre-married last name. She seems to have come from very little. Perhaps her father was a barber, there were a few references to that among contemporaries. It seems she worked to keep her origins hidden. In any case, this makes her story all the more interesting given the difficulty of transcending class in England at that time. We don’t really know how she was educated either. She probably learned basic reading somewhere and then educated herself by going all-in on reading on her own. She probably was either Catholic or an extremely high-church Protestant.

At some point in the early 1660s, Behn traveled to Suriname, the English sugar colony on the northern tip of South America. This is about the first solid information we have on her and that largely because she wrote about it. She seems to have come back to England in 1664 and married a German merchant named Johan Behn. He didn’t live long it seems and she was on her own again, but she used his name for the rest of her life. She was a big supporter of the Stuarts, that we know. Using whatever connections she had–again, she scrubbed her biographical information as clean as anyone possibly could–she got attached to the court of King Charles II. We know that she was recruited as a spy to go to Antwerp in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. In fact, this is the first 100% sure biographical information we have of her. The idea was for her to connect with an Englishmen there and recruit him to spy on anti-royal English living in the city, but the guy seems have told the Dutch that she was a spy herself. Plus it seems the government forgot to pay her, she had to hock her jewelry, and eventually just came back to London.

So Behn had to work now. She had read a lot and so she started writing. She had mostly written poetry on her own but she got a job in the royal theater companies to write plays. They were hopping because that asshole Oliver Cromwell had closed them down as part of his No Fun for Englishmen platform and now everyone wanted to go again. So she got work. She started with a play in 1670 called The Forc’d Marriage, a sexy tragicomedy of the type that the king liked. This solidified Behn working under the leadership of Thomas Betterton, who ran Duke’s Company and was a leading actor of the period as well. She had a couple more plays over the next couple years that were less well-received and then the historical record loses track of her again. We run into her again back in the theaters in 1676, when she wrote a bunch of pretty successful plays in row. Her biggest play became The Rover, in 1677, which is a sexy romp of English tourists through Naples during Carnival. And by this time, she was probably the second most prominent playwright in England, behind only John Dryden.

Though women were excluded from politics, Behn had no problem using her words to attack the Whigs in Parliament who dared question where Charles II should be replaced by James II even though the latter was a Catholic. She wrote plays that were openly pro-Tory and attended exclusively by Tory supporters in London. But when she went too far in criticizing an illegitimate son of Charles II, he ordered her arrested. Luckily for her though, he died shortly after and nothing really came of that.

Where Behn came into my life is being assigned her book Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave as the leadoff book to an American Literature course in college. Seems like a pretty reasonable place to start such a course if you are serious about it. This was back in the era where students were expected to read short novels once a week in an upper division English course, so it’s a million years ago. This was published in 1688 and is based at least in part on her long-ago trip to Suriname. It’s about an African prince tricked into slavery and then sold to owners in that colony. He then organizes a slave revolt, which inevitably fails, and he accepts his death with great dignity. I haven’t read it in 30 years, but I recall it not being exactly a great novel, though certainly an interesting one. And it really is one of the first proper novels in English. There are other examples of this, mostly notably Pilgrim’s Progress and some have pushed the invention of the English novel back to Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur in the 1470s, though that’s really Anglo-Norman French. The point though is not which is the first real English novel, which in the end doesn’t actually matter. Behn was still helping to create a whole new way of telling stories in English with her work, which is far more important.

Also at the end of her life, she was invited to write a poem to the new King William III. But Behn was so furious that the Stuarts were evicted from power that she refused. So she probably was a Catholic in the end. Her last years were a struggle. Her health began to decline. Perhaps arthritis was a major issue, for supposedly she had trouble holding a pen in her later years. But she never did have that much money. I’m sure she got paid well for all her work, so I assume she spent in the manner of a 17th century elite. This meant she had to keep writing through the pain.

Also, there was a decline in theater attendance generally in the 1680s and so Behn’s work wasn’t making as much as before as owners figured it made more financial sense to put on well-known old plays than promote new stories, which is basically the same strategy film studios use today by creating the 781st film in the Marvel Universe or some new Star Wars garbage. This is all part of the reason she started writing prose, including of course Oroonko. So I guess that’s a big unexpected benefit of the decline in theater profits for playwrights, because no one is reading Behn’s plays today, I don’t think. Though who reads any plays in this degraded era where everyone is busy cycling through effectively the same true crime shows on Netflix over and over again or playing stupid games on their phones? I mean, no one is reading Dryden anymore either, not to mention Arthur Miller or Tennessee Williams. It is a true wonder the modern person is so susceptible to fascism.

Behn was kind of forgotten for a long time until early 20th century English women writers began to reclaim her, most especially Virginia Woolf, who was a big fan. Feminist writers and critics of the 70s also embraced and led to a lot of new editions of her work being published.

Behn died in 1689. She was 48 years old. Not sure what caused her demise.

Aphra Behn is buried in Westminister Abbey, London, England.

If you would like this series to visit women writers of the United States, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Note, I will also take requests to visit French writers if you want to send me to Paris. Plus Edith Wharton is outside Paris. Someone has to sacrifice. Anyway, Sarah Orne Jewett is in South Berwick, Maine and Zora Neale Hurston is in Fort Pierce, Florida. I’d even break my usual boycott on entering Florida for that one. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.