This Day in Labor History: August 3, 1931

On August 3, 1931, the Unemployed Council in Chicago led black residents in protecting the furniture of a 72 year old resident of South Side being evicted from her home The cops responded by firing into the crowd, killing 3 people. This is one small moment in the larger history of Black economic activism in the 1930s that by the end of the decade led to the city being a center of Black labor politics.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters had risen as the first Black union in the American Federation of Labor and the leadership of A. Philip Randolph was critical in this. He was a great man and a great democratic socialist. But we shouldn’t overstate the power of the BSCP. The Great Depression absolutely crushed Black communities. Millions of Black people began leaving the South in World War I, finding jobs in northern cities. Those communities kept growing. But their economic stability was shaky at best. They were often the last hired and the first fired and that meant the Depression decimated these communities and that included the Sleeping Car Porters. In 1933, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters had 658 members nationwide. But the Porters had a strategy to build power in Black communities and that was using their relative power to build alliances with Black organizers on other issues, which over time, helped rebuild that union and also made it perhaps the key organization of grassroots civil rights in the decade after 1935.

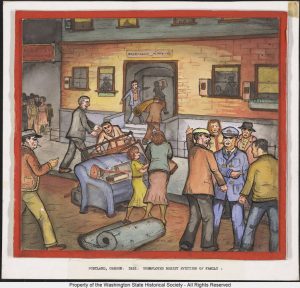

One of the big issues plaguing Black communities in the Depression was eviction. Landlords wanted to be paid, even if they owned ratholes that they didn’t care about making habitable for humans. Renters often could not pay because they did not have jobs. So what was to be done? For the landlords, it was to use the cops to evict people. For Black organizers and radicals, it was an opportunity to organize the people around something that was quite meaningful for their lives, not some abstract theory. The Brotherhood was not a communist organization. But it proved willing to work with communists on issues that mattered to its base among Black Chicago. Beginning in 1928, alliances slowly built. The communists were organizing heavily on tenant rights, trying to stop evictions.

On August 3, 1931, a landlord evicted a 72 year old woman named Diana Gross from her apartment. The Unemployed Council, which was the official name of the Chicago based organization fighting for tenant rights, gathered 2,000 people in front of the apartment to protect her things and stop the eviction. That’s a lot of people. They were able to do this by months of organizing, particularly of young unemployed men who were angry at a system that placed them in endless poverty and wanted to fight back. Not surprisingly, the landlord called the cops. They threatened the group and felt threatened themselves. They started arrested protestors, which only led to greater tensions. Then they fired into the crowd, killing three men. Between 5,000 and 8,000 showed up for an epic funeral march through the south side of Chicago.

This is one moment in a much broader movement to organize Black Chicago that included the communists, the Porters, the NAACP, Ida B. Wells’ network, and other Black groups. The NAACP organized around “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns. Different groups lobbied against the Hoover administration’s nomination of the racist John Parker to the Supreme Court. All of this would create significant alliances that would press the New Deal ahead locally by the mid 1930s, eventually leading to the Porters getting a contract from Pullman in 1937.

The Brotherhood built on the larger Black organizing campaigns in the 30s such as the anti-eviciton campaigns through its focus on Black manhood. This idea has a very long tradition, going back to slavery, that is complicated but generally revolves around men being able to protect their families and especially their women from the terror of white society, which could range from rape to eviction. Like the men who stood up and even died in protecting women from eviction, the Porters were able to win a union contract–or at least they portrayed themselves as such–without begging or asking. They did it through power. This attitude had grown significantly through Chicago’s Black community through the 1930s.

This then laid the groundwork for Chicago’s Black workers becoming core to the expansion of the CIO after 1936. CIO organizers in Chicago came to rely on the various solidarity networks that had built up through the decade. Their demands as men, and this is quite specifically gendered that way, tapped into long traditions in the community. Their ability to act as such and secure that contract only reinforced those idea. Unlike many labor unions, about which much of the Black community was divided, the Brotherhood’s specific appeal as men standing up for themselves and their families, as the communists had done in fighting eviction, brought these two movements together for mass organizing in the late 30s. Unions such as the United Packinghouse Workers of America became strong interracial unions with a lot of Black leadership based on ideas such as this, finally bringing unionization to meatpacking three decades after Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle and as eastern Europeans were moving out of these still horrific jobs and Black workers were moving in.

Part of the reason this worked is that Brotherhood activists became involved in these larger struggles. They showed up in solidarity at communist-led actions around unemployment and tenancy. Critical to this was abandoning the politics of civility that dominated the middle class, especially the NAACP, and engaging in the politics of mass action that mobilized everyday people, even as it often outraged or at least made uncomfortable middle class leaders in the churches and professions.

A post such as this almost inherently must be a bit inexact, for it is difficult to trace these claims directly. But we also lose understanding of how communities organize if we demand precise equations that this action and this other action led to that result. It just doesn’t work this way. The slow building of activist capability is long and difficult and inexact. We need to embrace these realities in our understanding of both the past and the present.

The Porters would take these politics national with the March on Washington movement in 1941 that forced a very reluctant Franklin Delano Roosevelt to desegregate the defense industry instead of having his nation’s racism shown to the world.

I borrowed from Beth Tompkins Bates, Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America, to write this post.

This is the 573rd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.