Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,888

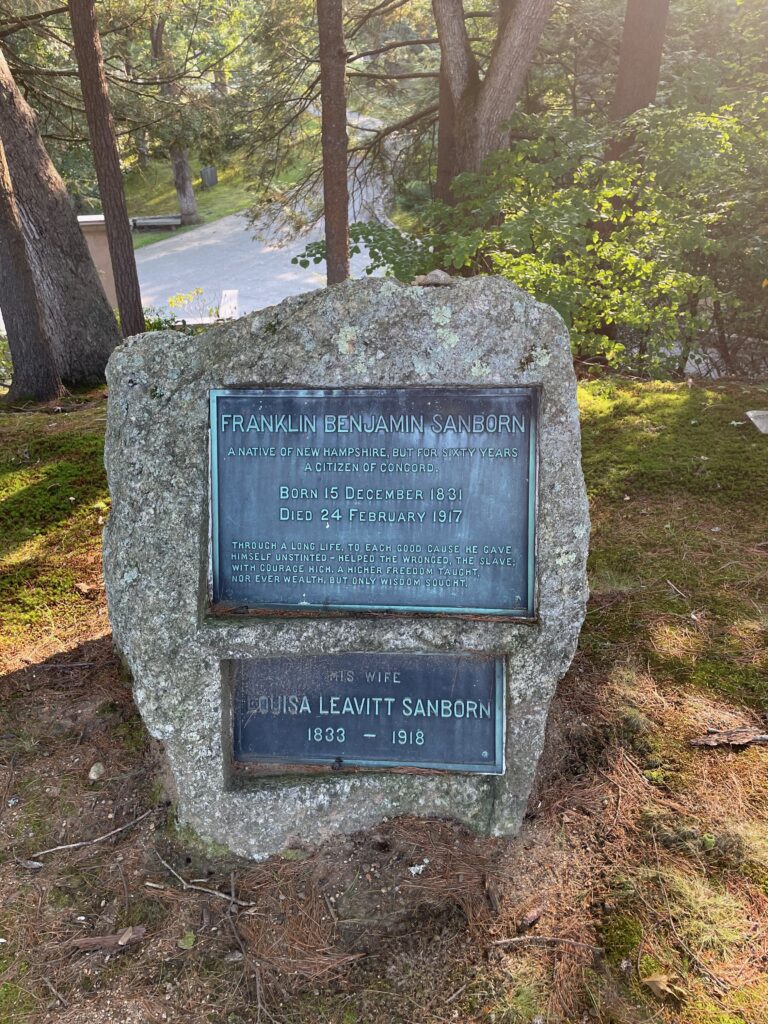

This is the grave of Franklin Sanborn.

Born in 1831 in Hampton Falls, New Hampshire, Sanborn should have died at the age of two. He was struck by lightning. Whether he remembered the experience, I don’t know, but for the rest of his life, he claimed he could change the world since he survived that. An unusual kid to the say the least, he read a lot of newspapers as a kid and at the age of 9, he declared himself an abolitionist to his family, who were evidently not believers in that cause. In any case, he was a good student, studied Greek, got into Phillips Exeter based on his skill, and then went to Harvard. All that took a bit more time than some students, so he graduated in 1855, at the age of 23.

Sanborn kept those abolitionist views and he became active in the Free Soil Party. He became one of the suppliers of John Brown, the Secret Six of major abolitionists funding his armed rebellion. The rest were George Luther Stearns, Gerrit Smith, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker, and Samuel Gridley Howe. So hey, I’ve now seen them all, which is kind of a personal accomplishment, if you are insane like I a m. Most of them were quite a bit older than he. Sanborn, like almost all of them, initially disavowed his connection to Brown, but he later came to defend his old friend after his execution.

In fact, Sanborn really did have a lot to fear from being involved with Brown. In 1860, federal marshals showed up to arrest him. He was in Concord, Massachusetts, and like ICE with immigrants today, they tried to take him in public. But as opposed to what happens today when people just open their phones to film what is happening, around 150 people rushed the marshals and took Sanborn back. Now that’s resisting governmental evil. Sanborn later remembered, “[The marshals] slipped a pair of handcuffs on my wrists before I suspected what they were doing, and tried to force me from the house. I was young and strong and resented this indignity. They had to raise me from the floor and began to carry me (four of them) to the door where my sister stood, raising a constant alarm. My hands were powerless, but as they approached the door I braced my feet against the posts and delayed them.”

Louisa May Alcott wrote of this in her diary: “Sanborn was nearly kidnapped. Great ferment in town. Annie Whiting immortalized herself by getting into the kidnapper’s carriage so that they could not put the long-legged martyr in.” I guess he was tall too. Henry David Thoreau described Sanborn as the activist “that calmly, so calmly, ignites and then throws bomb after bomb.” That was definitely a positive description for Thoreau.

During the Civil War, Sanborn edited the prominent newspaper The Commonwealth. He would remain actively involved in journalism for the rest of his life. After the war, Sanborn is somewhat less prominent. He was basically a wealthy liberal involved in various social reforms, but never as famous and he was an abolitionist. He did manage to insult the family of Ralph Waldo Emerson while courting the writer’s daughter so that didn’t work out. He ended up marrying a woman who looked exactly like him. I’ve seen this before in the flesh and love is love, but it’s weird to see.

Sanborn became the secretary of the American Social Science Association in 1865 and remained in that role all the way until 1897. Eventually, this became the National Institute of Social Sciences after Sanborn’s death. A lot of his interests had to do with disability and with prison reform. He worked with the Clarke Schoo of the Deaf to try and help figure out education for the hearing impaired. He also worked with the National Prison Association. Prison reform has always been a minefield on reform because most of the people who came to it basically considered prisoners people to experiment upon, which is how slightly before Sanborn’s time, you have people successfully arguing for solitary confinement so prisoners can contemplate their crimes, which of course just turns people into insane maniacs. But I don’t know too much about Sanborn’s involvement in the prison realm so I will let this go for now.

Sanborn also was a big charity guy. He was secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Charities in the mid 1860s and closely involved with it for most of his life. As such, a lot of his work was about investigating the broken institutions that destroyed what limited welfare state there was, such as the horrendous scary mental institutions that were unspeakable. The state created a new board to govern charities in 1879 and named Sanborn to lead it. One upshot of all this–in 1880, Sanborn was visiting an institution for the blind. A young woman named Anne Sullivan, who could see a little bit, asked him to have her released so she could attend a real school. He worked that out and she later became Helen Keller’s teacher.

Later in life, Sanborn and family took on the care of the aging poet William Ellery Channing, moving him into their house. He also spent his later years writing about his Transcendentalist friends, including books on Thoreau, Hawthorne, Samuel Alcott, and Emerson. I assume the latter avoided discussion his failed marriage proposal. Naturally he wrote a book on John Brown too. He edited a two volume edition of Theodore Parker’s writings, published in 1914. His last book, Sixty Years in Concord, came out in 1916.

Sanborn lived seemingly forever. In 1917, he was run over by a railroad baggage cart that was out of control. That might not have killed a younger man, but it knocked him down, he broke his hip, and he died shortly after. He was 85 years old. He was just about the last remaining leading abolitionist alive. I mean, the U.S. was to enter World War I just a few months later, so his biggest life events were a long time ago!

Franklin Sanborn is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other abolitionists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Elijah Lovejoy is in Alton, Illinois and Elizur Wright, who in addition to being an abolitionists is known as the “father of American insurance,” is in Boston. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.