This Day in Labor History: March 20, 1882

On March 20, 1882, workers at Homestead Steel won their strike, bringing the union into the steel works for the first time. One of the biggest victories for workers in the Gilded Age, it would lead to Homestead leadership dedicating themselves to stop at nothing to eliminate it ten years later.

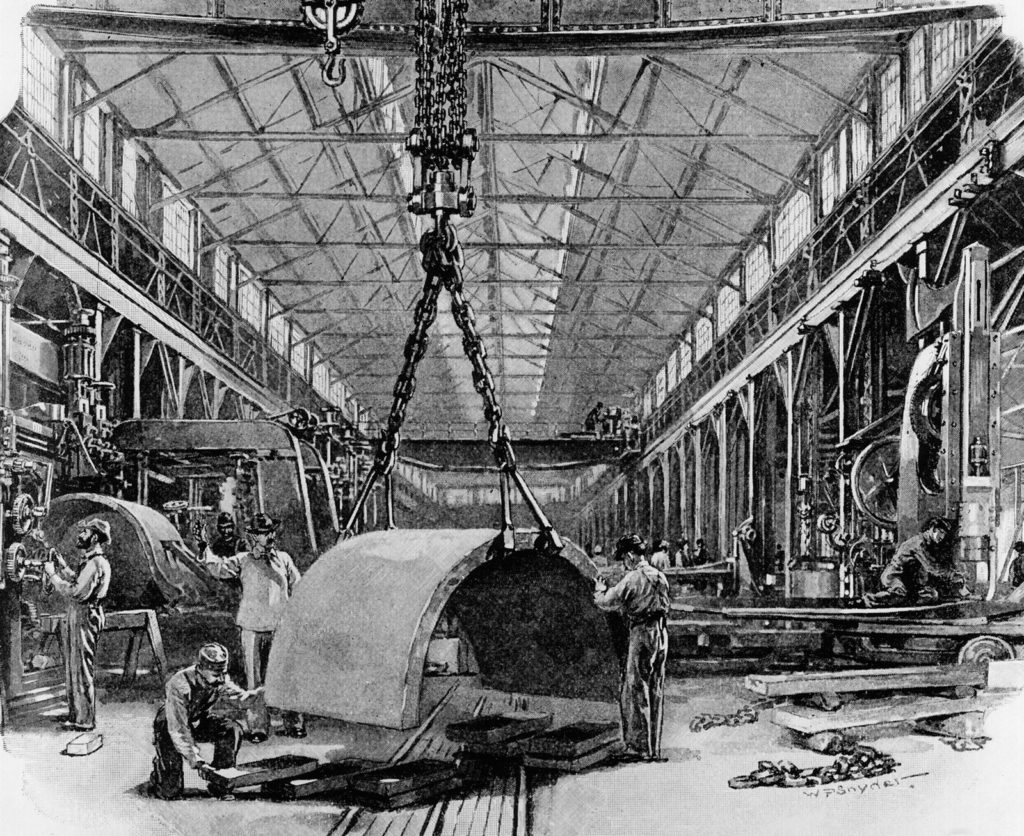

After the Civil War, working in iron and steel was considered to be a skilled position. These workers began to form unions to protect their privileges and control over their work. In 1876, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers formed. This would become the premier union of the iron and steel industry. Mostly located in the iron plants on the western edge of the Alleghenies, it soon moved into the bigger steel plants. It worked to establish standard wages and a hiring hall that would give the union some control over who entered the job. Moreover, it sought to control the speed of work.

We might think of late nineteenth century unionism as a battle between radicalized workers and industry. And sure, there was some of that. Those are the famous, iconic moments of labor history. But the big battle was between skilled workers trying to hold on to control over their work processes and employers seeking to turn them into wage slaves. Over this issue would be decided the future of the American workplace. It was hardly an inevitability worker control over production processes would lose out to the deskilling of labor, but that is indeed what happened. In this phrasing, “workers control over the means of production” is closer to worker control over their daily lives than it is about actually owning the factories, which they basically didn’t care about. This was a major purpose of the AA.

The big new steel mills represented both a threat and an opportunity for these skilled workers. If they could not organize these mills, they likely had no future. If they could, they could vastly expand their union and obtain control over work in them. The AA had a huge victory in 1881, organizing the Bessemer Steel Workers in Pittsburgh. Next up was the Homestead Steel Works in the town by the same name just to the east.

Homestead workers were agitated through 1881, including a brief strike during the middle of the year. By January 1, Homestead’s manager, William Clark, told workers they had to sign a contract that gave managers control over work processes by January 5 or he would shut the mill down. Moreover, his “contract” also prohibited AA membership and prohibited groups of three of more workers quitting at the same time without giving at least three days notice. The entire work force refused to sign and walked off the job. The National Labor Bulletin described Clark’s offer as “slave-binding” and “un-American.” Indeed it was. Ironically, Clark himself had been a strong union man on the steel shop floor before entering management. Clark immediately called upon the governor of Pennsylvania to send in the state militia and at least threatened to ask President Harrison to send in the federal military. But Homestead was an armed camp.

It was a pretty violent time. Shootouts and gunfights between strikers and sympathetic community members on one side and scabs and hired thugs and the state militia on the other side became common. Some scabs were nearly beaten to death. Authorities feared this would spread into a larger strike that would shutdown Pittsburgh. Some of this was ethnic in orientation; most of the strikers were central and southern Europeans and the scabs were largely northern European, particularly Swedes. Strikers were thrown out of company houses. The company claimed the union was a violation of their “republican rights” and as good Americans, they would never allow such a monster. This did fit into the twisting of free labor ideology during the Gilded Age to be a full-fledged defense of absolute property rights over any other consideration. But the Homestead workers also marshaled ideas of republicanism to their side, with claims that skilled workers controlling their own lives were part of the promise of free labor and the nation’s history. Moreover, what gave workers power was that if they withheld their labor at key moments, they could shut production for days because the entire process of heating the enormous factory’s works would have to begin anew.

The workers were able to hold out. Tensions increased through February. There were more evictions, more fights, more threats of expanding the strike. But by March 1, the strike was hitting Clark and the other Homestead managers where it hurt: the pocketbook. Orders were piling up and those clients were growing increasingly impatient. It had already defaulted on one order and the client was filing a lawsuit to recover damages. That day, Clark withdrew the demand that workers sign his draconian contract. But he still claimed he would only rehire company men, not unionists. On March 2, a new battle erupted between strikers and scabs, with the militia escorting the scabs to work. But workers won this battle and the mill remained closed. That evening, the cop presence in the town increased. The town’s residents went nuts over this and beat two cops into unconsciousness. The AA denounced violence but the violence worked. More of the factory had to shut down with the scabs too scared to try and work.

By this time, the company was on the defensive. A March 14 agreement sought to compromise on most matters, but left the principle of the company only taking back what union men it wanted. The AA assumed that would mean most if not all unionists. But it was only 68. The strike continued, with more violence over the next week. Finally, on March 20, Homestead management gave in after a final set of negotiations where the workers demanded to choose their own replacements if they were out sick. Clark refused this, but did agree to have an entire shift of added union men ready to go so that they would be replace by other unionists, not scabs. The AA organized Homestead. It was a huge victory for the workers. They still controlled the shop floor.

However, this was only the first battle. Andrew Carnegie purchased Homestead in 1883. He, the vile Henry Clay Frick, and the rest of the steel management class despised the AA and wanted it destroyed. In 1889, an attempt to bust the union backfired when the mill workers and the townspeople united in opposition to the mill. The workers went on strike after Homestead refused to negotiate a new three-year contract. They won that strike overwhelmingly, effectively controlling the work process after that time. That infuriated Carnegie and Frick, which led to the dramatic and famous 1892 strike when Carnegie fled to Scotland, too cowardly to over see this himself, told Frick to do whatever he wanted, and then called in the Pinkertons to bust the AA. That did take the plant back from the union and the steel industry would spend the next 45 years as one of the most horrifying employers in American industry. Not until the Steel Workers Organizing Committee won representation from U.S. Steel in 1937 would a strong union return to the mills. And by that time, the battle to control work processes was long over, completely won by the companies.

I borrowed from Paul Krause, The Battle for Homestead, 1880-1892 to write this post.

This is the 386th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.