Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 719

This is the grave of Gilbert Stuart.

Born in 1755 in Saunderstown, Rhode Island, Stuart grew up in comfortable circumstances. I’ve driven by this house hundreds of times as it is on the way to where I work, but I’ve never actually stopped at the little museum there. Shame on me. But it’s a good sized house for the time. His mother came from a big land-owning family and his father started the first snuff factory in the U.S. That factory was in fact in the basement of their house, which must have smelled just dandy, so it’s not like we are talking about luxurious circumstances of the well-off a century later. But for the time, this was comfort.

Anyway, in 1761, the family moved to Newport, where his father was a now a merchant in that early center of American trade. Stuart went to school there and very quickly showed great promise as a painter. He became a protege of the Scottish artist Cosmo Alexander, presently living in Rhode Island. In 1771, Alexander took him to Scotland. But when Alexander died the next year, Stuart, still too young and unknown to make a living in the British art scene, returned to Rhode Island.

When the American Revolution began, Stuart, like lots of rich people, were royalists. The British economic system worked for lots of people in the colonies and the American Revolution was very much a civil war. Probably more people supported independence than actively opposed it, but not by that much. Plus a whole lot of people didn’t care either way and just wanted to be left alone to farm. Stuart left New England in 1775 for London and stayed there through the duration of the war. In 1777, he met another American painter in Britain, Benjamin West, and became his protege, which helped him a lot. He worked in West’s studio for five years, providing him the real artistic training he needed. This also meant studying both the old masters and the rich British art scene, which at that time was very heavy on both landscapes and portraits. The former was seen as more artistically pure but the latter paid the bills. He painted his first acclaimed portrait, of Sir William Grant, a wealthy lawyer and future member of Parliament, in 1782. This made him famous. He could be rich. Except that he was horrible with money and despite being able to raise large amounts through his commissions, was nearly thrown into debtor’s prison. In 1787, he had to flee to Dublin to escape this fate, but nearly faced it again there.

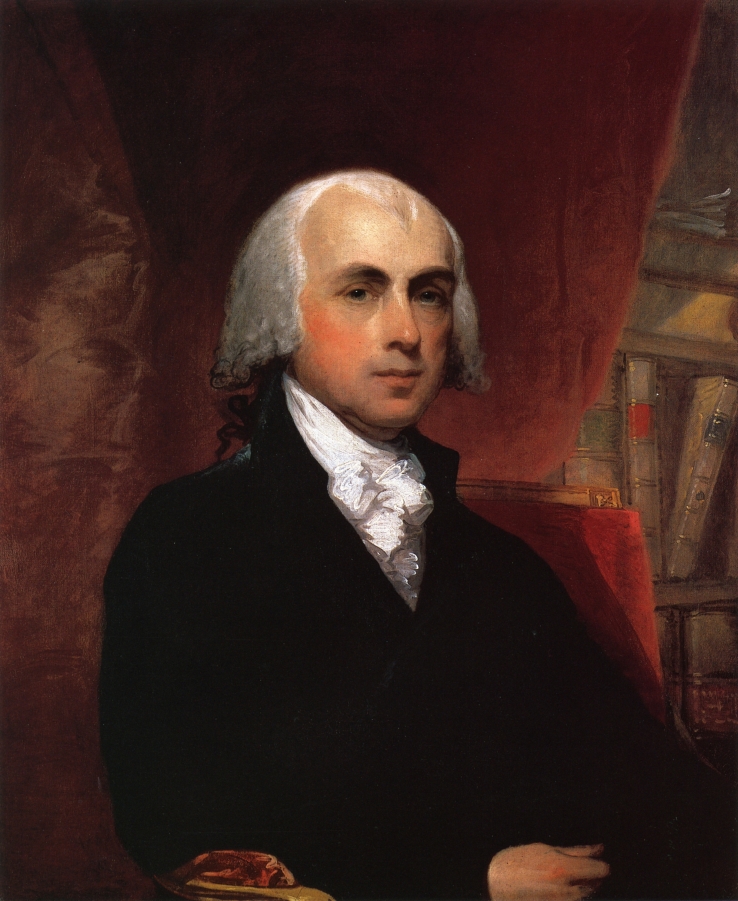

By this time, Stuart had a family and needed money and a fresh start. So in 1793, he returned to the United States with a very specific goal: paint a portrait of George Washington, have it engraved, and then sell a ton of copies to Americans so that he could have a stable income. This took some time, but the next year, he painted John Jay, who then introduced him to Washington. He first painted the revolutionary hero in 1795 and for the next four years, until Washington’s death, produced a series of iconic portraits that indeed made him a ton of money on the reproductions. One of these of course is the basis for Washington’s picture on the $1 bill. Ironically, that portrait was never actually finished. Like everyone else who met Washington, Stuart found him unusually inscrutable. He stated, “An apathy seemed to seize him and a vacuity spread over his countenance, most appalling to paint.” But it worked out, even if not every portrait is first-rate.

These Washington pictures made Stuart famous in his original land. He opened a studio in Washington, D.C. nearly as soon as the new capital was marginally suitable for human habitation, in 1803. But he only stayed there two years before decamping for Boston, where he would live the rest of his life. There wasn’t much difference in his life no matter where he lived. He could raise a ton of money very easily but spent it faster than he could raise it. He painted well over 1,000 portraits of leading Americans, including each of our first six presidents. Now, sitting for a portrait was certainly seen as a symbol of prestige, which very much came over from 18th century British art. But let’s face it, sitting for that long is very boring. Stuart made it work because he was such a good conversationalist. John Adams wrote,

Speaking generally, no penance is like having one’s picture done. You must sit in a constrained and unnatural position, which is a trial to the temper. But I should like to sit to Stuart from the first of January to the last of December, for he lets me do just what I please, and keeps me constantly amused by his conversation.

Art historians have claimed that Stuart’s British portraits are better than that of his American portraits. I don’t really know nor do I have the training to even evaluate such claims, though I like the American portraits a lot because they are a sort of classic Americana that helped create the mythology around the Founding Fathers, as problematic as that can be in many ways. The claim however rests on a pretty solid foundation, which is that Stuart was never sympathetic to American republicanism and simply preferred the elite life of Europe, so the subject matter interested him much more. He thought Americans were bores and American cities lacking in any culture at all. He was known to stop working on material, even if he had already received the money, if he got bored. But in the United States, there was no competition for good portrait painters at the British level, so he could be difficult and still get commissions. Also, like any good Englishman, he hated the French, including French art.

Stuart was also pretty cranky. He had a big ego in a period of big egos. Functionally, what this meant is that the Enlightenment men of the time would have opinions about art and how he should paint. When these were expressed, he would kick them out of his studio. In essence, Stuart combined a contempt for the wealthy he needed (making him unlike the solicitous painters of the time reliant on patronage), a fully open commitment to making money through portraits instead of other types of art that were seen as more artistic, and a desire to live a bohemian life that included a whole lotta booze, and I assume also gambling. He gave extravagant dinners and bought expensive musical instruments he could not afford.

Stuart worked until 1826, despite having a stroke in 1824. He died in 1828. He was so bad with money that his family was left near destitute. Some of his problems may have been that he was manic depressive. I am as skeptical of armchair psychology as anyone. But he was known at the time to swing between incredible periods of hard work where he just whipped out great work and periods of depression where he didn’t get out of bed for weeks. It would sometimes take him 15 years to actually finish a portrait, which drove everyone from Thomas Jefferson to Abigail Adams batty. But he was the best, so what were you going to do? So this armchair diagnosis does make some sense.

They were so poor that they could not buy him a gravesite. A carpenter who owned a small plot on Boston Common gave it to them on the cheap. The Boston Athenaeum held a fundraiser for the family by charging for an exhibition of Stuart’s portraits. Within a decade, since it wasn’t Stuart managing anything, the family was financially just fine, in part because his daughter Jane became a quite prominent portrait painter herself. By this time the family had moved to Newport and purchased a suitable grave site there. But they weren’t sure where dad’s body was exactly so they left him there and put up a grave marker more or less where he was buried.

Let’s look at some of Stuart’s work.

Gilbert Stuart is buried in Central Burying Ground, Boston, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other American portrait painters, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. A large number of these people are in Europe, so if I ever get to England or back to France, then I can gather a lot there. But in the U.S. Grant Wood is in Anamosa, Iowa and Thomas Eakins is in Philadelphia. Previous posts in this series are archived here.