Facing Freedom

First off, hello! How’s everyone doing? It’s been awhile.

I made a tiny human back at the end of the summer and have been a little preoccupied with keeping him alive since then. True story: I got all inspired to write my first post of 2020 on the notable drop in journal submissions by female academics since the pandemic hit—but couldn’t find the time. Now that the semester is final over, I’m hoping to pop by here with more regularity again. Plus, I just couldn’t leave this one alone.

***

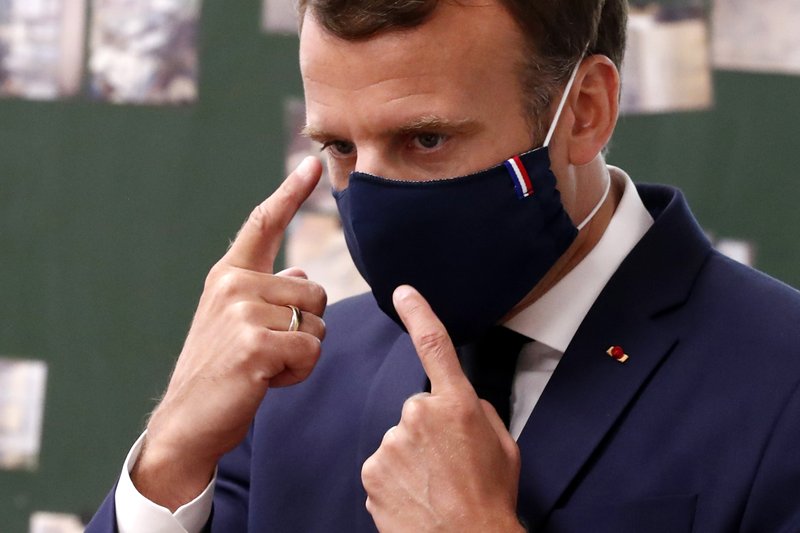

Earlier this week, the Washington Post raised an issue I’d been mulling over: how will France navigate the conundrum of prevalent mask-wearing for public health while maintaining a ban on face-coverings?

As of May 11, French residents are permitted venture outside, with an easing of the initial fairly restrictive measures (previously, folks could only leave their houses for a defined set of essential reasons—and carrying an appropriately signed, timed, and dated form). To allow for this new freedom of movement, masks are now mandatory on all public transport and in most school settings; businesses are likewise encouraged to require masks. Masks already had an established presence as a potential mitigator for infection. Online guides to mask choice and care were showing up in mid-April, around the same time I got an email offer for designer masks from a Paris dress shop.

So far, so 2020. But as I placed my own order for some functional fashion (because, full and sheepish disclosure, I totally did), I wondered how exactly this fit with the past few decades of wrangling over the right to wear (or right to forbid) face-coverings.

Back in 2010, France passed the so-called “burqa ban,” which outlaws “concealing” faces in public spaces. Article 2 specifies that exceptions can be made for “health reasons,” as well as for “professional motives,” sports, celebrations, or artistic expression. As in the 2004 ban on “conspicuous” religious symbols, the text of the law itself carefully avoids targeting Muslim women explicitly. The National Assembly report on the 2010 law, however, openly admits that the ban was inspired by “legitimate” concerns about the niqab and devotes most of its discussion to the ways that wearing a full veil poses a threat to “social cohesion.”

While the 2004 law had been justified as a defense of laïcité (French secularism), the 2010 study invoked a deeper social contract:

In free and democratic societies, the implicit but elementary rule theoretically prevails that no exchange between persons, no social life, is possible in public space without reciprocity of regard and visibility: people meet and enter relations with open faces.

And this is where the story stops being just about the French Republic’s repeated failures to manage racial and religious diversity, because the same fetishization of bared faces has become a hallmark of “freedom” for the anti-lockdown crowd.

Not only are masks apparently the latest trend in government overreach, but they are also rapidly coming to signal a frightening form of “liberal” politics assumed to be at odds with American mores—and democracy itself. Take, for example, the woman who accosted a masked reporter in Ohio and accused her of “terrifying the general public.” On the one hand, one wonders how promoting personal hygiene is more terrifying than, say, storming a state legislature while brandishing rifles (or mounting an armed defense of a barber shop). On the other hand, we should all recognize by now that “terror” is only created by certain types of people. Just below the surface of the French veil laws lurks a slippery chain of perceived associations between Muslim religious practice and radical violence.

We certainly don’t wear our masks equally in the US. Black men have to worry that masks are yet another item of clothing that makes them susceptible to increased suspicion and violence. COVID-19 coverage regularly relies on the trope of masked Asian faces, even as anti-Asian racism and hate crimes spike. Xenophobia makes it possible to promote concrete border walls against people while repudiating cloth barriers against viral infection.

There’s an irony here in that anti-mask laws on the books in the US mostly arose as an anti-KKK measure, though there was indeed an active Anti-Mask League during the 1918 flu pandemic. Further irony comes from the fact that more recent anti-mask enforcement is intended to strengthen state surveillance, while masks themselves subvert the government power supposedly vilified by those protesting health measures. Once again, therefore, we have to confront the reality that only some of us are deemed worthy of the right to avoid surveillance, while others must remain fully visible and vulnerable.