Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 582

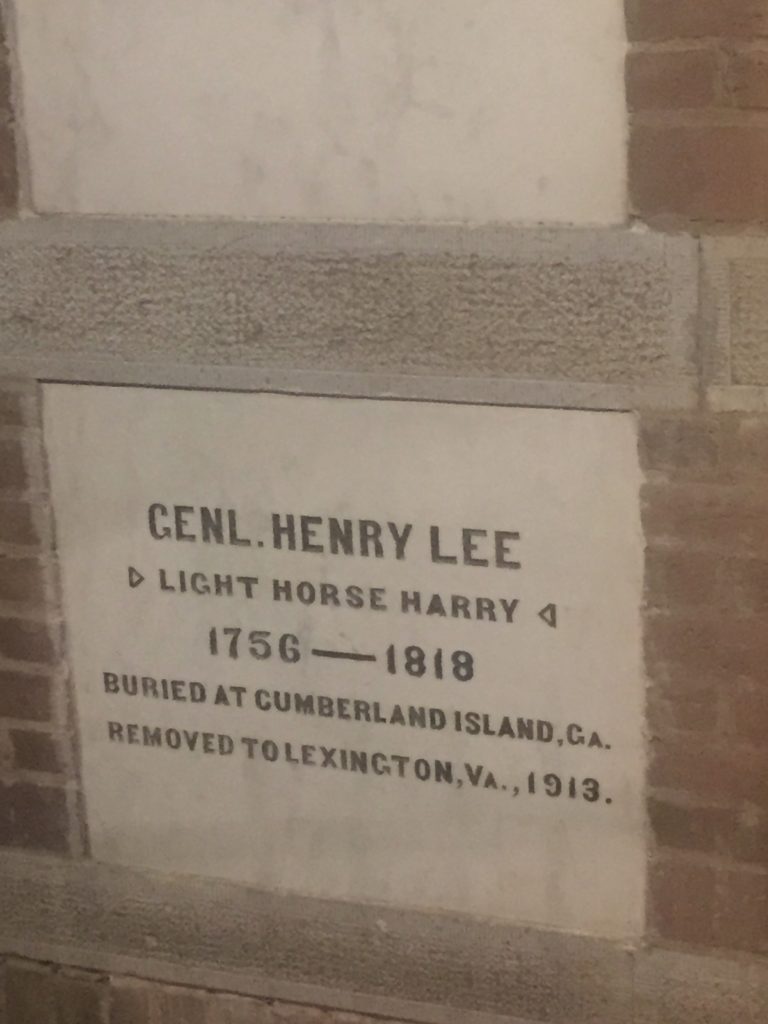

This is the grave of Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee.

Born in 1756 in Dumfries, Virginia, Lee grew up in the colonial Virginia elite that would soon be the leadership of the United States. He graduated from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1773 and started studying the law. But when the American Revolution started, Lee left the law and became a captain in a Virginia regiment. He proved extremely effective despite being very young. He defeated Hessian regiments in battle and achieved his nickname through his superior horseman skills. The Continental Congress gave him a gold medal–the first non-general to get one–in 1779 for his actions during the Battle of Paulus Hook. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and was with Frances Marion and Andrew Pickens in the South Carolina and Georgia campaigns of 1781, including at Guilford Courthouse and Ninety-Six. He was at Yorktown too. But he left the Army shortly after, having a lot of differences with his fellow offices.

Lee went into politics at this point while building up his extensive plantation holdings and owning of human beings. He was in the Congress right before the Articles of Confederation were tossed out. He supported Virginia adopting the Constitution and became a staunch Federalist and supporter of Washington and Hamilton as the First Party System developed. He was governor of Virginia between 1791 and 1794. When the Whiskey Rebellion took place in western Pennsylvania and Hamilton wanted to run roughshod over some farmers, Washington asked Lee to rejoin the military, commanding nearly 13,000 militia members. But that was settled without violence. He officially rejoined it in 1798 when during the quasi-war with France. Now a major general, Lee stayed in the military for two years, leaving again in 1800. Jefferson brought him back again in 1808, when it seemed the U.S. might go to war with the British. Despite his strong Federalist leanings, Lee agreed, but again, no fighting resulted. When the War of 1812 started, Lee actually wanted to have a commission, but James Madison refused to grant him one, which seems like a big mistake to me.

In 1812, Lee published his memoir of fighting in the southern theater of the Revolution. By this time, he needed the money. In 1801, after his second military stint, he had gone back to Virginia to manage his plantation. But as was the case for many of the Virginia elite of his era, it was a total failure. Between the decline in the price of tobacco, the inadequacy of any crop to replace it, and the fancy living these people had come to expect, plantation after plantation was in big trouble, including those of Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. It wasn’t any better for Lee. He had also placed a lot of his resources in the hands of Robert Morris, who notoriously went bankrupt and brought a lot of prominent Americans down with him. In 1809, Lee spent an entire year in debtor’s prison. He lost his plantation entirely and the family moved to Alexandria, Virginia.

Still a strong Federalist, Lee didn’t really support the War of 1812, even as he was willing to lead troops in it. There was a Federalist newspaper in Baltimore called The Federal Republican. In July 1812, there were serious threats against its editor by a mob of Jeffersonians. Lee went to Baltimore to defend his friend. This was not a good idea. Fearing the mob, he and his friends surrendered to the Baltimore police so they could have refuge in jail. Didn’t work. The mob forced its way into the jail and pulled out all the Federalists. Then they started torturing the people inside, including Lee, over a period of several hours. This included being beaten in the head with a club and thrown down a flight of stairs. Someone tried to cut off his nose with a knife, but didn’t quite succeed. His closed eyes were pulled open and candle wax dripped in. Lee suffered major injuries from the beating he received, mostly internal injuries but also he was just generally beaten to a bloody pulp, not to mention what was left of his nose. We often don’t really know just how incredibly violent early American politics and cities were. This is one window into the general awfulness of the period.

He never fully recovered. He had speech problems after this and probably had PTSD. He spent a few years at home attempting to recover, but never quite did. He took a trip to the West Indies to recuperate, but on the way back, he died in Cumberland Island, Georgia, in 1818. He was 62 years old.

Light Horse Harry Lee is buried in the Lee Shrine, built for his treasonous slaver son, on the campus of Washington & Lee University, Lexington, Virginia. As you can see from the vault in the crypt, he was moved from his initial burial in Georgia when this absurdity was built in 1913.

This grave visit was funded by LGM reader contributions. Thanks! If you would like this series to visit other Revolutionary War figures, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Charles Lee is in Philadelphia and Israel Putman is in Brooklyn, Connecticut. Previous posts in this series are archived here.