Confirmation Bias is a Hell of a Drug, Part I

The first time I ever really registered the existence of Drop Site News is when its newsletter started to appear in my inbox. As best I can tell, Drop Site is a kind of spinoff of The Intercept, with politics that are Grayzone adjacent. It received a $250,000 grant from the Open Society Foundation to underwrite its operations from September until November of this year which.

The site has been running a series of posts under a category entitled “Epstein and Israel,” all of which are written by Ryan Grim and Murtaza Hussain. I’ve seen a few people refer to these reports here. Van Jackson — an important academic voice in progressive foreign policy — has repeated Grim and Hussain’s reporting uncritically.

Last week I read one of the installments. I found it deeply troubling. It chronicled behavior that would be gross even without Epstein’s involvement. But it also contained enough red flags to warrant serious skepticism. The issue was less any of the specific facts that it offered, but more how the authors framed the material and spun out its implications.

I decided to look more closely at the rest of the series. Having done so, my takeaway is that mainstream news media’s relative lack of interest in Drop Site’s reporting is not, as I’ve seen suggested on social media, a result of pro-Israel bias. It is, rather, a matter of responsible journalism.

This is the first of a series of posts. Each one will discuss a single report, in the order of its release. I want to be clear that I do not expect to analyze each and every installment. But I will try to cover all of the ones currently on the site.

Preliminaries

According to Grim and Hussain, their reporting is based on documents acquired “by Handala, a pro-Palestinian hacking group with speculated ties to Iran.” As they explain:

The documents were posted by Distributed Denial of Secrets, a non-profit whistleblower and file-sharing website. Although the emails lack cryptographic signatures, they contain a vast amount of unpublished private photographs and documents from Barak and his inner circle, including information that was not publicly known at the time.

Later installments contain information from the recent Epstein email dump, which Grim and Hussain also say that they used to verify overlapping documents.

Let’s start with a basic question: should we reject evidence drawn from the hacked documents out of hand?

I don’t think so, but I am not in a position to independently verify any information that Grim and Hussain source solely from the putatively hacked documents. I just don’t have the relevant expertise. So rather than speculate, I am going to proceed on the assumption that we can trust their assessments.

That being said, we should keep in mind some of the risks of dealing with material abstained from information operations. Absent proper forensic analysis, we have no way to know if otherwise genuine documents used in the story were altered prior to their release, whether the collection was curated in misleading ways, and whether fake documents were inserted alongside real ones.

I commend Grim and Hussain for being very clear about their sourcing. I would have liked them to be more explicit about their level of confidence in the veracity of each of the specific documents that they used —at least those that aren’t easy to check in the Epstein emails.

I also want to flag an issue in some of the articles: The authors sometimes use “Israel” as shorthand for “former Israeli government officials and Israeli firms.” It is not unreasonable to think that Israel — like pretty much every country in the world — conducts government business via private parties. I would certainly expect that, at minimum, it treats individuals and firms doing business overseas as intelligence assets — that it debriefs them when they return home, for example. And always keep in mind that Israel’s approach to international affairs is ruthlessly power-political. But, again, the same is true of a lot of other states.

Nonetheless, American journalists do not typically describe overseas deals made by Blackwater, Meta, Oracle, or other more U.S. firms as action by the “United States.” For example, In 2019, Reuters reported on the role of former U.S. government officials — including many who previously worked in the U.S. intelligence community — in helping the UAE expand its cyber capabilities.

[Richard] Clarke’s work in creating DREAD launched a decade of deepening involvement in the UAE hacking unit by Beltway insiders and U.S. intelligence veterans. The Americans helped the UAE broaden the mission from a narrow focus on active extremist threats to a vast surveillance operation targeting thousands of people around the world perceived as foes by the Emirati government.

One of Clarke’s former Good Harbor partners, Paul Kurtz, said Reuters’ earlier reports showed that the programme expanded into dangerous terrain and that the proliferation of cyber skills merits greater U.S. oversight. “I have felt revulsion reading what ultimately happened,” said Kurtz, a former senior director for national security at the White House.

At least five former White House veterans worked for Clarke in the UAE, either on DREAD or other projects. Clarke’s Good Harbor ceded control of DREAD in 2010 to other American contractors, just as the operation began successfully hacking targets.

A succession of U.S. contractors helped keep DREAD’s contingent of Americans on the UAE’s payroll, an engagement that was permitted through secret State Department agreements, Reuters found.

The programme’s evolution illustrates how Washington’s contractor culture benefits from a system of legal and regulatory loopholes that allows ex-spies and government insiders to transfer their skills to foreign countries, even ones reputed to have poor human rights track records.

American operatives for DREAD were able to sidestep the few guardrails against foreign espionage work that existed, including restrictions on the hacking of U.S. computer systems.

Despite prohibitions against targeting U.S. servers, for instance, by 2012 DREAD operatives had targeted Google, Hotmail and Yahoo email accounts. Eventually, the expanding surveillance dragnet even swept up other American citizens, as Reuters reported earlier this year.

In an interview, Mike Rogers, former chairman of the U.S. House Intelligence Committee, said he has watched with growing concern as more and more former American intelligence officials cash in by working for foreign countries

“These skill sets do not belong to you,” he said of ex-U.S. agents, but to the U.S. government that trained them. Just as Washington wouldn’t let its spies work in the pay of foreign nations while employed at the NSA, he said, “Why on God’s green earth would we encourage you to do that after you leave the government?”

Even though Clarke told Reuters that “the plan was approved by the U.S. State Department and the National Security Agency” and that “The NSA wanted it to happen,” the article does not conflate their activities with those of the country as a whole.

It should also be clear that Israeli firms are not the only players in the market for state surveillance and cyber-espionage. Nor are Israelis the only former government and intelligence officials involved in the business of digital repression.

Ehud in Mongolia

The first post on “Epstein and Israel” reports on Ehud Barak’s dealings in Mongolia. If you’ve never heard of Barak, he has served in the Israeli government as prime minister, Deputy Prime Minister, Defense Minister, Interior Minister, and Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was elected leader of the Labor party in 1997, and was Prime Minister from 1999 until 2001. Barak withdrew Israeli forces from Lebanon in 1999 — without providing adequate warning to Israel’s Lebanese proxies. He participated in Bill Clinton’s final effort to secure a two-state solution at Camp David, which ended in failure and recriminations. Barak’s time in office arguably helped discredit the peace process for many Israelis; it marked the start of what would prove a catastrophic decline of the Labour Party.

Grim and Hussain begin their post with a provocative claim:

Jeffrey Epstein used his political network and financial resources to help broker a security cooperation agreement between the governments of Israel and Mongolia, according to a trove of leaked emails from former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. This new set of emails between Barak and Epstein has largely been ignored by the mainstream press, but includes crucial new context on Epstein’s operation.

As they write a few paragraphs later:

In the shadows of Israel’s cyber boom was Jeffrey Epstein, who exploited his network of political and financial elites to help Barak, and ultimately the Israeli government itself, to increase the penetration of Israel’s spy-tech firms into foreign countries. Epstein actively supported the Israeli intelligence industry via venture capital investments and contributions to charitable organizations – “non-governmental” entities that laid the foundation for official Israeli security deal-making. The story of Israel’s 2017 security agreement with Mongolia is a window into the true nature and scope of Epstein’s operation.

But this is all in the forward. In the body of the article, they write that:

Not physically present, but helping coordinate events behind the scenes, was Jeffrey Epstein, according to a trove of hacked emails between Epstein and Barak posted by Distributed Denial of Secrets and confirmed as authentic by Drop Site. Epstein, a New York financier and elite fixer who later became notorious for his role as a sex trafficker of underage girls, died in jail in 2019. In addition to his criminal activities, he also used his elite connections to broker an agreement for Israel, the emails reveal.

Barak’s visit to Mongolia aligned with a visit by Terje Rød-Larsen, president of the International Peace Institute, a non-profit think tank specializing in multilateral diplomacy. Barak and Rød-Larsen were both members of Epstein’s social circle, and well-acquainted; Rød-Larsen was a key mediator in the 1993 and 1995 Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, when Barak led the Israel Defense Forces. Before Barak left government, at least by 2010, the two maintained an informal backchannel in Barak’s personal email inbox, scheduling meetings and sharing articles on international diplomacy.

On April 21, 2013, Barak arranged a meeting at Epstein’s New York mansion for an “overview of the coming days.” The next day, Rød-Larsen sent Barak an email with details for a proposed advisory team consisting of “internationally-recognized experts” who could facilitate foreign investment in key industries in Mongolia. The draft proposal highlighted the great “opportunity” of Mongolia’s “massive natural resources (mostly minerals and metals),” promising to accelerate Mongolia’s economic growth and bolster its international status. Barak replied to Rød-Larsen’s proposal: “Thoughtful, far looking and necessary.”

It does seem like Barak communicated with Epstein at various times while in Mongolia. As this and their later posts document, the two were entangled in various ways.

(If you haven’t looked through a sample of Epstein’s emails on other websites, the ones with Barak are consistent with Epstein’s correspondence with other business, political, and academic elites. I don’t know about you, but reading the Epstein emails makes me repeatedly reach for my pitchfork — that is, when they’re not triggering intense bouts of nausea.)

At this point in the story, it seems like Epstein’s only major role was as a dinner host for two people, Barak and Rød-Larsen, who already knew each other pretty well and were already in communication with one another. Grim and Hussain report that it was Rød-Larsen, not Epstein, who provided Barak with a sketch of a plan and information about Mongolia.

There is, however, more.

The archived conversations show Barak and Epstein arranged two more meetings in New York on April 22 and April 24. Barak landed in Ulaanbataar in the evening of April 26, according to an itinerary emailed by the Consul General of Mongolia to Israel. Early the next morning, Barak tried to reach Epstein for a final phone call: “Jeff hi[.] I can’t reach you on any phone. Pl try calling me. In about an hour I shall start meetings here. It’ll be more complicated.”

What follows are a lot of other details that seem unrelated to Epstein. Barak meets with officials. He delivers a handgun as a gift. He emails Viktor Vekselberg, for whom he was working as a consultant. In that email, he asks for help in a way that’s reminiscent of his earlier email to Epstein. Grim and Hussain do not provide details about additional communication between Barak and Epstein while the former was in Mongolia, and it is not clear that there were any.

Rød-Larsen was also in Mongolia at the time.

On April 29, in between meetings with Mongolian officials and events marking Mongolia’s presidency of the Community of Democracies, Rød-Larsen chaired a panel discussion on the Arab Spring at a democracy promotion event in Ulaanbataar, which Barak joined as a participant. The same day, Rød-Larsen signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Mongolian Foreign Minister Luvsanvandan Bold to deepen the country’s cooperation with IPI.

Grim and Hussain reports that “Epstein began recruiting his associates to participate in IPI’s Mongolia advisory council.” But the evidence for this is a single email, sent months after Barak was in Mongolia. In it, Epstein suggests that Larry Summers (jeebus) would be a good person for the board. Barak email back that ““I think greatly of him especially in re to advise for Sovereign Heads. We can complement each other effectively with a lot of synergies.”

Grim and Hussain next describe the makeup of the advisory council — basically a number of former heads of state. They provide no evidence that Epstein had any role in their recruitment. The group meets in Davos; Epstein is one of the people who joins by telephone. “Epstein’s professional affiliation in the meeting agenda was listed as ‘financier.'” They describe some of the meetings minutes, which include bog-standard suggestions for Mongolian reforms. Epstein recommends a general audits.

What happens next? Grim and Hussain quote an email in which Barak asks Epstein for advice on getting paid for “his participation on the advisory board.” They note that “On May 2, 2014, Epstein pinged Barak to remind him to deliver a Mongolia proposal to Rød-Larsen.” The proposal was for Mongolia to expand its internal surveillance capabilities.

All of this may strike readers as underwhelming, but things do get more interesting.

For the next year, progress stalled: IPI tried unsuccessfully to schedule a one-on-one follow-up meeting between Barak and President Elbegdorj in late 2014. Then, in March 2015, Epstein loaned Barak $1,000,000 to fund an early-stage Israeli startup called Reporty Homeland Security. The company was co-founded by Pinhas Buchris, a former commander of both Israel’s Unit 8200 military intelligence unit and Unit 81, a high-tech intelligence unit. Reporty (now rebranded as “Carbyne”) enables emergency dispatchers and security services to retrieve precise location data and live video/audio feed from phones. The company was being piloted in local municipalities in Israel, and they planned for an international launch in November 2015.

On September 26, 2015, Epstein invited Barak, Rød-Larsen, President Elbegdorj and Foreign Minister Lundeg Purevsuren to his home in New York for dinner. Purevsuren emailed Barak and his wife later to say he enjoyed the meeting, and made plans to visit Israel. Five days after the dinner, on October 1, Rød-Larsen authorized payment of $100,000 to Epstein from IPI funds earmarked for the Mongolia Advisory Board, according to the Norwegian newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN). IPI has denied that Epstein ever received any payment from the Institute and DN found no explicit confirmation Epstein received the funds.

According to Drop Site, Epstein and Barak spend time in 2016 pitching “Reporty’s emergency response platform platform to potential investors,” although it looks more like Epstein helped Barak get a meeting with two of Peter Thiel’s partners, who declined to back the venture.

Then Grim and Hussain report that:

In late 2017, Mongolian and Israeli security officials met in Ulaanbaatar. They agreed to cooperate on emergency services, and discussed “introducing Israeli advanced technology into [the] Mongolian emergency service.” In 2019, medical officers from the Israel Defense Forces participated in joint military exercises with the Mongolian Armed Forces for the first time.

While he played a vital part in helping lay the groundwork for the 2017 agreement between the two countries, based on his private correspondence with Barak it is unclear if Epstein helped execute this final step. Epstein’s emails to Barak’s personal inbox abruptly stopped shortly after April 22, 2016, the week of Ghislaine Maxwell’s deposition about her email contact with Epstein in Giuffre v. Maxwell in the Southern District of New York. Barak’s use of his personal email also tapered off around this time.

Wait. What?

[Epstein] played a vital part in helping lay the groundwork for the 2017 agreement between the two countries

There is absolutely no evidence in the post that Epstein did anything to “lay the groundwork” for this agreement. Nothing. Nada. Zilch.

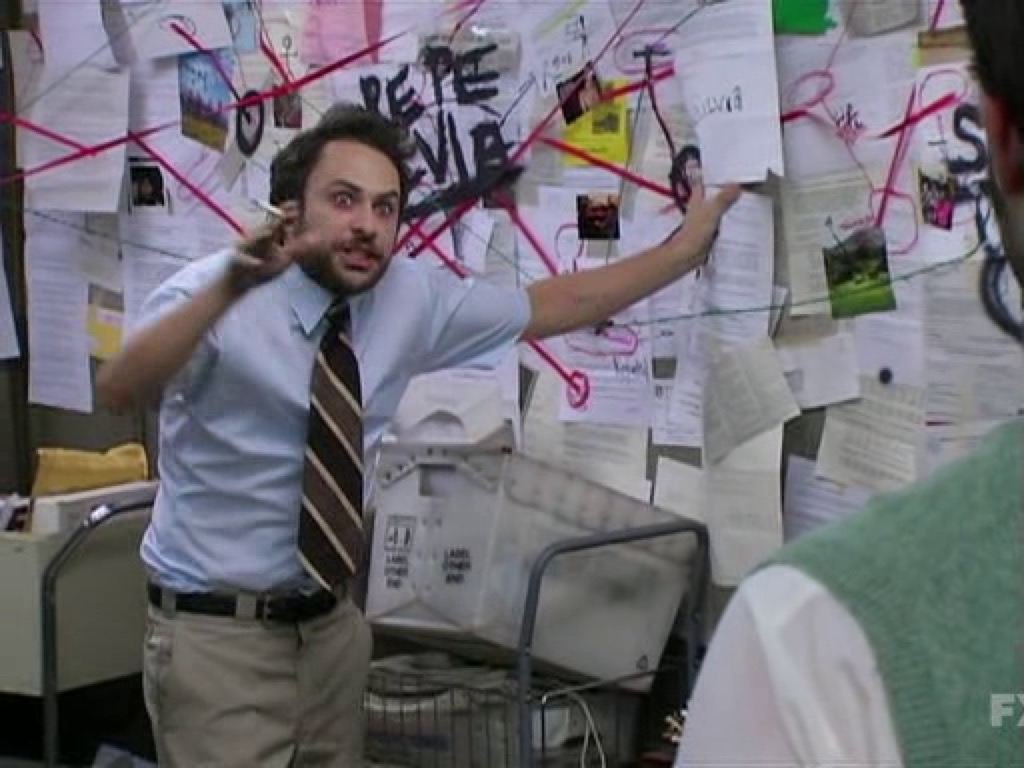

In fact, I was so taken aback when I reached this paragraph that I went back through the report. Had I missed something?

Well, there’s the aforementioned memo. According to Grim and Hussain, “The proposal’s letterhead bears the official Emblem of Israel, which requires approval from the Israeli Minister of the Interior, over Barak’s name.”

If you’re an expert on Israeli law concerning the use of official emblems, now’s your time to shine. Because I’ve read the page they link to a bunch of times. It looks like a talk page from a wiki. If it actually says that using the emblem without permission is illegal, I keep missing it. But let’s say it is. Do we mean illegal as in “you’re going to jail” or illegal as in “technically there’s a fine but nobody gives a shit?” And if the Minister of Interior actually said “sure, Ehud, you can use that symbol” why would that be smoking gun evidence that Barak was not only on official business, but that he was teeing up an agreement that Mongolia and Israel signed three years later?

Okay. Let us pretend that there’s some kind of there there. What, then, was Epstein’s “vital part,” exactly? Hosting a dinner between two people who were already in contact? Reminding Barak not to forget the memo? Providing starter money for a project that, at least as far as the article details, went nowhere?

I would be remiss by not discussing how the post ratchets up its description of Epstein’s role as it progresses.

Recall that, at the outset, Grim and Hussain and write that Epstein “help[ed] broker the agreement.” Later on, they claim that Epstein “played a vital part in helping lay the groundwork for the 2017 agreement between the two countries.”

In the final section, they up the ante even further:

But his role in the Mongolia Advisory Board plan and his intimate contacts with Barak, private sector tech firms tied to Israel’s security establishment, influential non-governmental organizations, and senior foreign government officials, show for the first time that he engaged in activities that altered the relationship between states—in this case, building formal security ties between the government of Israel and Mongolia.

Uh, no.

What they actually show, as best I can tell, was that Epstein successfully maintained and leveraged his contacts — in no small measure, I suspect, because of his willingness to throw his money around.

Barak comes across as simultaneously pathetic, grasping, and devoid of basic morality. As do a number of other ‘global elites.’

What the article says about Grim and Hussain, I will leave to readers to sort out.

What about Israel? if you’re not already outraged over Gaza and the West Bank, then I doubt throwing Epstein into the mix is going to change your opinion of Israel or its conduct.

ETA; edit for spelling and clarity. I will probably do a final edit later.