Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,988

This is the grave of George Meany.

Born in Harlem in 1894, Meany grew up in the union world of New York. His father was a plumber and a union official. He instilled all those values in his son. He dropped out of high school when he was 16 to become a plumber and joined the United Association of Journeymen and Apprentices of the Plumbing and Pipe Fitting Industry of the United States and Canada. His father died in 1916 and so George supported his younger siblings and mom there for awhile. By 1920, he was on the executive board of Local 463 and became a business agent for the union in 1922. He was proud that he never had to strike while he was a business agent. This would say a lot about his attitude toward the labor movement generally. When industry struck against his union through a lockout in 1927, he sued and won an injunction to end the lockout. It usually went the other way.

Ambitious, he became the head of the New York Federation of Labor in 1934 and worked to elect labor Democrats and socialists to office through the 30s, serving the needs of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and other Democratic leaders, as well as labor Republicans such as Fiorello LaGuardia. By 1937, he was secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Labor. Now, this was just as the Congress of Industrial Organizations had left the AFL, bringing in the principles of mass organization around industrial unionism and big strikes to make it happen. For men like Meany, this was anathema. He was interested in politically conservative craft unionism and nothing else. He would ride to the top of the labor movement on this principle.

Almost immediately, while being part of the New Deal state apparatus to get labor to not strike in the war, Meany made alliances with labor anti-communists such as Jay Lovestone and this would be critical to the rest of his life. Meany outright supported the Taft-Hartley Act, the most notorious anti-union law in American history, because he cared a lot more about hurting leftists and undermining the CIO than he did about organizing workers.

By 1951, AFL leader William Green was starting to get sick and would die shortly after. Meany took over the daily operations of the AFL and become its head in 1952. Meanwhile, Taft-Hartley and other mistakes by the CIO, plus the fact that the AFL now had to organize industrially in order to compete with the CIO, had undermined the reason for the labor movement to be split. So in 1955, they merged. This was not a happy merger for a lot of CIO leaders, especially Walter Reuther. Meany basically despised Reuther and while the UAW would be the leader of the AFL-CIO’s Industrial Union Department, Meany clearly ran the show.

By the 1950s, Meany was much more interested in killing communists overseas than he was in organizing American workers. He happily assisted the CIA in undemining leftists. From the CIA-led coup against Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954 to the CIA-assisted coup against Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973, Meany would be all-in in attacking democratic unions and democratic governments if they did not do what the CIA wanted. If Meany did do anything really positive in these years, it was taking on corrupt unions, including kicking the Teamsters out of the AFL-CIO during the Jimmy Hoffa years. He was highly concerned with the corrupt unions giving the entire movement a bad name. After all, if there was one thing that really mattered to men like Meany, it was that unions be seen as respectable parts of American life that should be embraced and welcomed. There were multiple sides to that–yes, that included disciplining and eliminating leftists in the movement, but it also included making sure that the unions were clean and did not give the movement a bad name.

Meanwhile, the nation was changing and Meany didn’t care that much for it. He had a very complex relationship with civil rights. He wasn’t really an outright racist, but he didn’t care much about it. He certainly had little interest in supporting the movement. It was Reuther who paid for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. But the AFL-CIO did officially support the Kennedy civil rights bill. It is said that Meany however was so moved by Randolph’s speech at the March that he created the A. Philip Randolph Institute to promote African-Americans in the labor movement. Meany also continued loathing Reuther and seeking to undermine the UAW, industrial unionism, and Reuther personally at every opportunity. In 1967, they had it out at the AFL-CIO annual convention. Reuther demanded Meany democratize the council. Meany refused and pretty much laughed in Reuther’s face. Reuther responded by pulling the UAW out of the AFL-CIO entirely. That cost the federation a lot of dues, but Meany didn’t care much. He was happy to be rid of the man who wanted American unions to actually do something.

Meany’s most infamous moment came in 1972, when he refused to allow the AFL-CIO to endorse George McGovern for the presidency because McGovern opposed the war in Vietnam. This is such a depressing moment. First, McGovern represented the Democratic Party in revolt, the hippies who protested inside the disastrous ’68 Chicago DNC. In the aftermath, with rules changes to the Democratic Party structure to make it more democratic, the power of the AFL-CIO leadership within the Party was challenged, even as there was room for more rank and file participation. But worse for Meany, McGovern didn’t support the Vietnam War. There was another issue at play–the endless rivalry between Meany and the old CIO unions. Walter Reuther was dead by this time, but Meany and Reuther hated each other and what each stood for. Meany was highly concerned that the new social liberalism of the Democratic Party grassroots would empower the Reutherites both in the labor movement and in society as a whole. So undermining the social democratic unions in a new grassroots oriented Democratic Party was also on his mind.

What Meany did here was give the labor movement a bad reputation with the left for decades. Meanwhile, by this time he was an old man who was out of his element. He spent more time painting than he did organizing workers. There were increased calls for him to resign and he finally did so in 1979, after his wife died. The problem was that Meany’s policies were basically supported by the most of the labor movement, so they named Lane Kirkland AFL-CIO chief in his place. If you thought Meany had too much charisma and militancy, Kirkland was your man. Ugh. Unsurprisingly, the labor movement had no answers on how to recover from its rapid decline that began under Meany’s watch.

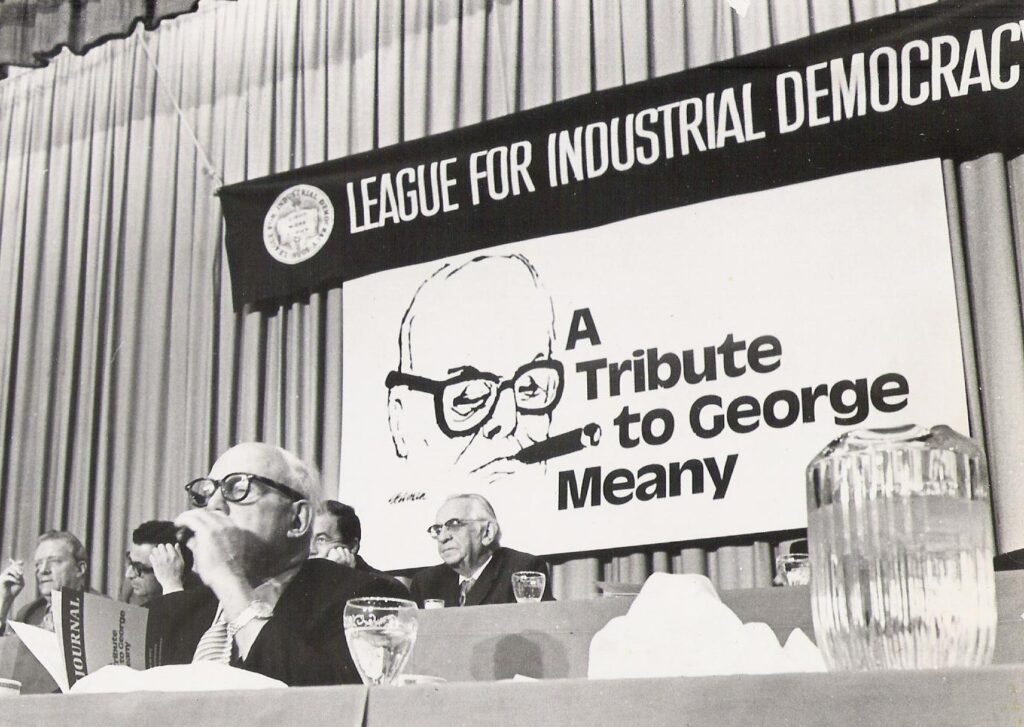

For me, the Meany era is summed up entirely in this picture–the cigar, the self-satisfaction men like this had about stuff being named for them and being honored, the completely out of touch with the actual American working class way men like this held themselves.

On the other hand, the Meany era gave material for Klassic Krusty.

This is truly ever labor historian’s favorite bit in TV history.

Meany did not live long after his retirement. He had a heart attack in 1980 and died. He was 85 years old. Yes, he stayed as president of the AFL-CIO until he was 84. The modern Democratic Party has nothing on the labor movement in terms of its commitment to gerontocracy.

Incidentally, one of Meany’s legacies in the labor movement was establishing the George Meany Center for Labor Studies (why not name if after yourself???) in 1969, which housed the archives of the AFL-CIO. He wanted the paperwork there for future historians. In 2013, unable to really care for this material, it donated it to the University of Maryland, but with a lot of stipulations. The core issue–those papers really demonstrated just how far the AFL-CIO had gone in undermining leftist worker movements for the CIA in the Global South and there has been battles ever since over what historians can actually look at because some of those people are still alive and even though that’s less so every year, the union movement still doesn’t really want the story of the Meany era told.

George Meany is buried in Gate of Heaven Cemetery, Silver Spring, Maryland.

If you would like this series to visit other labor leaders, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Can’t visit Hoffa! But William Green is in Coshocton, Ohio and Richard Trumka is in Morgan Township, Pennsylvania. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.