Politics as vacation

Ezra Klein wrote a really terrible piece in the immediate wake of Charlie Kirk’s murder, in which he claimed that Kirk — a hugely successful internet troll who created a right wing propaganda machine that played a non-trivial role in the ascension and subsequent return to power of Donald Trump — was someone who was doing politics “the right way.”

This inspired the NY Pitcbbot to achieve new heights:

Klein has had a few days to think things over, and I’m sorry to report that time to reflect isn’t helping.

Many appreciated the piece, particularly on the right. It saw their friend and ally more as he saw himself. There were many, closer to my own politics, who were infuriated by it.

Privately and publicly, they offered the worst things Kirk had said and done: starting a watchlist of leftist professors, busing people to the protest that led to the Jan. 6 insurrection, telling his political foes that they should be deported, saying the Democratic Party hates this country, saying the Civil Rights Act was a mistake. Friends said to me: Look, we can oppose political violence without whitewashing this guy.

Klein calls such things “the worst” of what Kirk said and did. A more cogent analysis would recognize that these were all completely characteristic acts on Kirk’s part, because Kirk dedicated his life to advancing the forces of ethno-nationalist (later conveniently explicitly Christian nationalist) authoritarian white supremacy, as embodied by Donald Trump, and the broader Trumpist political movement that is trying with considerable success to destroy liberal democracy in this country.

But worse than this sort of willful blindness is Klein’s remarkably obtuse complaints about how terrible “political violence” is:

My reaction to this, honestly, is that it is too little to just say we oppose political violence. In ways that surprise me, given what I thought of Kirk’s project, I was and am grieving for Kirk himself. Not because I knew him — I didn’t. Not because he was a saint — he wasn’t. Not because I agreed with him — no, most of what he poured himself into trying to achieve, I pour myself into trying to prevent.

But I find myself grieving for him because I recognize some commonality with him. He was murdered for participating in our politics. Somewhere beyond how much divided us, there was something that bonded us, too. Some effort to change this country in ways that we think are good.

This is both absurd and irresponsible. The irresponsible part is claiming that Kirk was murdered “for participating in our politics.” We don’t know why Kirk was murdered, but if I were to take a semi-educated guess it was not because he was “participating in politics,” but because he was Internet Famous, and murdered by a disturbed young man who also wanted to be Internet Famous. Saying Kirk was “murdered for his politics” will probably end up being about as accurate as saying that John Kennedy was murdered for his politics, or that Ronald Reagan or Donald Trump came close to being murdered for their politics. All these men were shot or shot at not because they were politicians — their specific politics seem to have been practically irrelevant to the would-be assassins — but rather because of their fame.

John Hinckley wanted to impress Jodie Foster, and it may well turn out that Tyler Robinson was just trying to impress Nick Fuentes, or his Discord internet friends. In any event, that seems far more likely to me than the idea that Kirk’s murder was some sort of ideologically motivated act in any sort of even minimally coherent way.

But worse yet is Klein’s frankly childish view of political violence in general:

I’ve seen many on the right struggling with the idea that Kirk’s assassination somehow reveals the impossibility, the futility, of normal politics: He tried to do it by dialogue, and look what happened to him.

What marks those who choose political violence is not their politics — it’s their decision to choose violence. That they make that decision, for whatever reason, does not justify your making that decision, for any reason.

We cannot give the lost or the mad a veto over the agreements and conduct that safeguard our society. That gives lone gunmen all the power — and it leaves us with nothing.

I don’t know what happened inside the mind of Kirk’s shooter. I have tried to imagine being his parents, being so excited for his path just a few years ago. I don’t think the question is: What politically radicalized the man who shot Kirk? I know many political radicals. They are some of the best people I know. I think the question is: What broke in him? This was not the act of someone thinking clearly.

But we still have to think clearly. When Nancy Pelosi’s husband was assaulted, when Minnesota had to grieve the assassination of some of its leaders, that did not render normal politics obsolete. It made normal politics all the more essential and beautiful. It was a reminder of the horror that lies on the other shore.

Oddly, Klein is recognizing on some level that he doesn’t even know if Kirk’s murder was a political act in any meaningful sense, and yet at the very same time also denying this, and framing that act as a conscious decision to choose violence over politics.

And that way of framing the matter is absurd. What sort of man can look at, to pick an example not at random, the Donald Trump administration, and all its acts, and all its words, and conclude that what we need is to make sure that “politics” is not contaminated by “violence? No man — only an enormous child, who has been given vast tracts of journalistic space on the nation’s most prominent editorial page.

Max Weber famously, but apparently not famously enough, defined the state as that entity which in a modern society has been granted a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. That state violence is still violence, and not some sort of widely televised political philosophy seminar, ought to be a banal observation, but Klein’s discussion of the matter reveals how heterodox this truism remains, in the minds of many reactionary centrists, which I’m sorry to conclude Klein has more or less definitively revealed himself to be

Politics is not an alternative to violence: it is the channeling of violence, to the extent possible, into the world of public rather than private decision making.

Klein’s visceral horror at a particularly spectacular — because he happened to actually see it — failure of a breakdown of that system is understandable:

His murder has shaken me pretty deeply: In the days after his assassination, when I’d close my eyes, I kept imagining a bullet going through a neck.

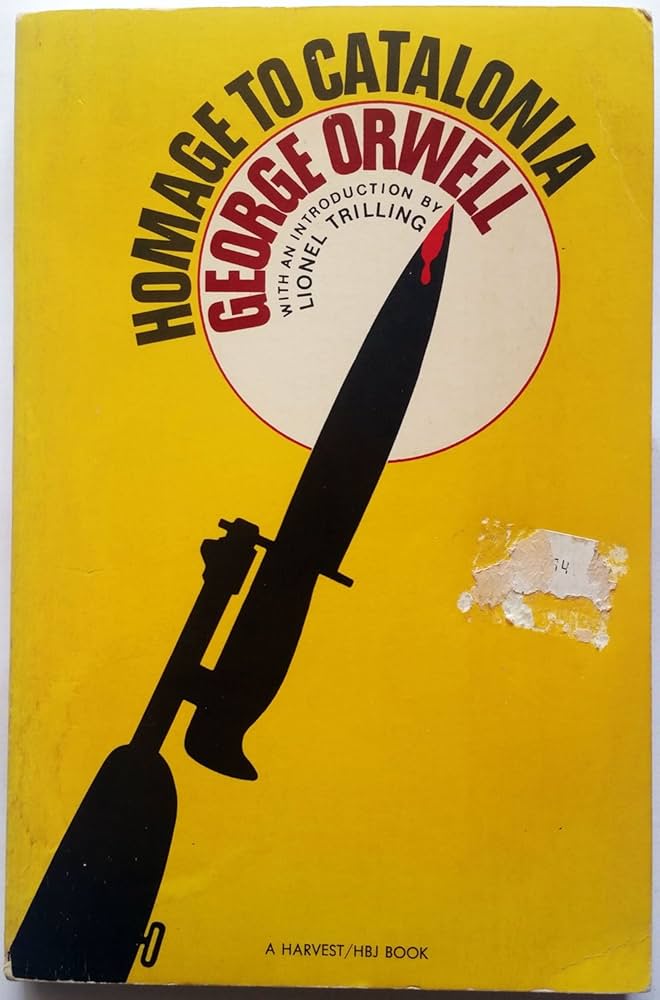

I don’t think there’s much mystery surrounding exactly whose neck Klein is imagining some hypothetical future bullet piercing. And Klein’s horror at spectacle of Kirk’s murder is a healthy and human reaction. Orwell:

But there is one other thing that undoubtedly contributed to the cult of Russia among the English intelligentsia during these years, and that is the softness and security of life in England itself. With all its injustices, England is still the land of habeas corpus, and the over-whelming majority of English people have no experience of violence or illegality. If you have grown up in that sort of atmosphere it is not at all easy to imagine what a despotic régime is like. Nearly all the dominant writers of the thirties belonged to the soft-boiled emancipated middle class and were too young to have effective memories of the Great War. To people of that kind such things as purges, secret police, summary executions, imprisonment without trial etc., etc., are too remote to be terrifying. They can swallow totalitarianism because they have no experience of anything except liberalism. Look, for instance, at this extract from Mr Auden’s poem ‘Spain’ (incidentally this poem is one of the few decent things that have been written about the Spanish war):

To-morrow for the young, the poets exploding like bombs,

The walks by the lake, the weeks of perfect communion;

To-morrow the bicycle races

Through the suburbs on summer evenings. But to-day the struggle.

To-day the deliberate increase in the chances of death,

The conscious acceptance of guilt in the necessary murder;

To-day the expending of powers

On the flat ephemeral pamphlet and the boring meeting.

The second stanza is intended as a sort of thumb-nail sketch of a day in the life of a ‘good party man’. In the-morning a couple of political murders, a ten-minutes’ interlude to stifle ‘bourgeois’ remorse, and then a hurried luncheon and a busy afternoon and evening chalking walls and distributing leaflets. All very edifying. But notice the phrase ‘necessary murder’. It could only be written by a person to whom murder is at most a word. Personally I would not speak so lightly of murder. It so happens that I have seen the bodies of numbers of murdered men — I don’t mean killed in battle, I mean murdered. Therefore I have some conception of what murder means — the terror, the hatred, the howling relatives, the post-mortems, the blood, the smells. To me, murder is something to be avoided. So it is to any ordinary person. The Hitlers and Stalins find murder necessary, but they don’t advertise their callousness, and they don’t speak of it as murder; it is ‘liquidation’, ‘elimination’, or some other soothing phrase. Mr Auden’s brand of amoralism is only possible, if you are the kind of person who is always somewhere else when the trigger is pulled. So much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don’t even know that fire is hot.

This sounds, in isolation, like it could be an unusually cogent conservative critique of leftist sangfroid about the “necessity” of political violence, but it was written by a leftist who wrote it while reflecting on his experiences in Spain, where he went to kill fascists, and got shot through the neck for his troubles.

Orwell was capable of being horrified by political violence in both its formally legitimate (ordinary war; law) and formally illegitimate (civil war; revolution; murder) guises, and of recognizing that political violence is completely inescapable, and therefore in some sense necessary, even in societies less riven by it than Spain in 1937 or America in 2025.

We can’t all be Orwell, but we should at least strive not to be Ezra Klein.