This Day in Labor History: August 19, 1969

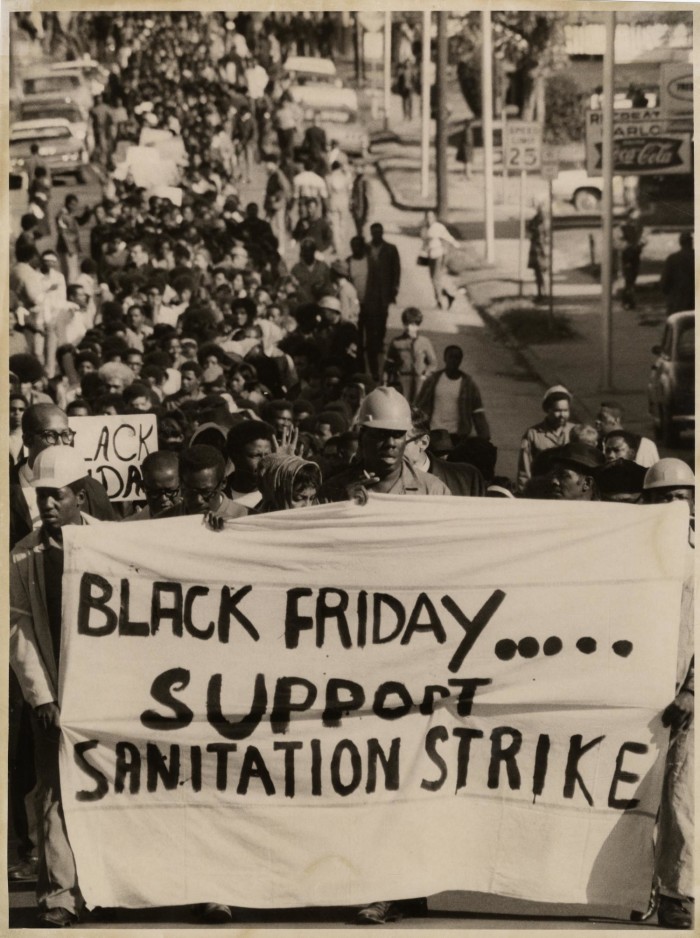

On August 19, 1969, sanitation workers in Oklahoma City went on strike. This civil rights oriented strike built on the successful Memphis strike the previous year that had become famous for the assassination of Martin Luther King while he was in town supporting it. It also demonstrated how activist workers didn’t even need a union in order to engage in a successful labor action.

Sanitation work was a job for Black men in the mid 20th century South, but it wasn’t much of one. Like nearly every other job in the South, it was a highly segregated world. Unions in the North had made some progress on fighting against racial job classifications, often against the demands of their own white members. But in the union-lite South, with stronger traditions of segregation, this had not much succeed by the late 1960s. Today, we have nearly completely forgotten about the economic justice demands of the civil rights movement, including that the actual name for that famous 1963 rally was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom that had demands for massive increases in the minimum wage and was largely paid for by the United Auto Workers. Talking about economic justice makes many people, including the Black elite classes, a lot more nervous than talking about segregation or voting rights, since it continues to make demands on those elites today.

For sanitation workers, there was little difference between union rights and civil rights. They needed one just as much as the other. Sanitation work is not inherently degrading or dangerous, but it sure was in the South at that time. Workers did not have proper equipment and so dealt with the grossest part of the trash in avoidable ways. The machines were often not well-maintained. This was a job that could kill you, which is in fact what started the Memphis strike the year before workers in Oklahoma City followed their example. Moreover, there was no way to get promoted. Effectively, all whites were above all blacks. Poverty wages predominated, with many workers making less than $500 a month, simply not enough to live a dignified life, which of course was the point.

By early 1969, sanitation workers and black community leaders, based out of the northeastern neighborhoods of Oklahoma City, began organizing to demand change. Critical to this was the local chapter of the NAACP. Often, at the national level, the NAACP was pretty disconnected from local struggles and in fact often eschewed involvement since it was the wrong kind of person involved in them–often militant, believing in direct action, and poor, which for people such as Roy Wilkins was the worst part of all of it. The great organizer Ella Baker had chafed against Wilkins for years before leaving the organization to work for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (where she chafed against many of the same problems with King), but she had spent years avoiding national offices and working at the grassroots to build up local leadership that would actually do something around community organizing. In Oklahoma City, this revolved around a woman named Clara Luper.

One of many forgotten local organizers of the civil rights era, Luper had been an NAACP leader since 1957. Moreover, she had led a sit-in movement in 1958, two years before the famous four students did so at Greensboro. Luper had a militant chapter of the NAACP ready for action and so the workers turned to this local organizing legend and she helped them find their own power. There had been plenty of practice too. We don’t often think of Oklahoma City as a major civil rights center, but that city had seen plenty of action in its movements, including for school desegregation and discrimination in hiring. The 1960s had seen the relative moderate white elements in the city try to forestall bigger movements by taking care of some of these issues upfront, which of course just led to the Black community seeing their power and ability to secure additional victories.

On August 19, over 200 workers walked off the job. The workers demanded both pay raises and the end of segregation at work. Strikers demanded the ability for promotion to drivers and supervisors. They also wanted increased pay. No union was involved. This was strictly a community-led labor action. As Heywood Boone, a strike leader, stated, “We are going all the way Mrs. Luper. She is our speaker. The City Manager said she couldn’t speak with us, but she is our speaker.” Over 25 Black churches led fundraising efforts for the strike. National NAACP sent some staffers to help. Of course, they were arrested almost immediately, but in 1969, the white power structure couldn’t be quite as blatant in repressing Black organizing as a decade earlier, so they were released after posting bond. On October 31, a huge rally in front of City Hall led thousands to demand justice for the strikers. Black customers also organized a boycott of white-owned stores downtown. Of course at the rally, the cops showed up in full riot gear with dogs and everything else, but they couldn’t unleash them.

The strike finally ended in November. This was after the Chamber of Commerce began really upping the pressure on the city to settle, as the strike had really started to impact the bottom line of businesses that had nothing to do with it. They might not like Black people, but they didn’t really care if those workers got paid more money to spend in their stores. The governor got involved too to help mediate it. It was not a total victory for the workers. Instead of the $100 raise demanded for workers making less than $500 a month, it was around $50. But they did get the 5-day, 40-hour week (remember that the Fair Labor Standards Act only covers the private sector) and they did get improved working conditions. Interestingly, one of the sticking points to the final settlement, at least according to The Crisis, which was the NAACP magazine, is that the city flat out refused to hire back the 11 leaders of the strike. But the strike wouldn’t end without them. So they found private sector jobs for those guys with assurances that they would not later be fired. I have no idea what actually happened after the strike ended. But that was the final issue before settlement.

This is the 532nd post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.