This Day in Labor History: June 22, 1916

On June 22, 1916, cops shot a Croatian miner named John Alar who was part of the Industrial Workers of the World-led strike in the Mesabi Range of Minnesota. This event did not succeed, because the odds were so stacked against the miners and the IWW. But it was another moment of working class revolt against the system that exploited them in the early twentieth century. It also led to concrete improvement in the mines as employers tried to siphon off some worker anger.

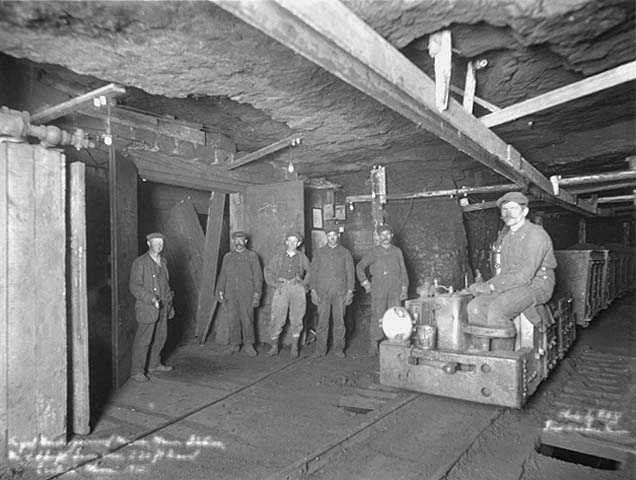

Conditions in the Mesabi Range mines were bad. Not only was work super dangerous, as it was in mines everywhere, but the system the employers had set up in this isolated place was pure exploitation. It was a contract labor system. What this meant was that workers were paid by how much they mined. That thus meant that workers with easily accessible ore got paid more than those working in more inaccessible areas and thus corruption resulted, with favored workers getting the good leads. Kickbacks were required for the good stuff. You can see how workers would be furious about this. Of course this also meant that most of the workers labored in deep poverty.

On June 2, 1916, a Czech miner named Joe Greeni (I don’t imagine this was his given name) gave a speech about the terrible wages and the sporadic payment. He inspired a bunch of his other workers to walk out of the St, James Mine in Aurora. Word almost immediately got out to the other mines and workers started walking off the job. Within a week, there were probably 8,000 or so miners on strike.

Like lots of the actions associated with the IWW, local workers started it and the IWW came in to offer support. This was fine of course and really fit with the IWW model pretty well. Workers taking control at the point of production could lead to the kind of general strike the IWW believed could spawn revolution. The Wobblies did have professional organizers, but they weren’t really like what one thinks of as a professional organizer today. They traveled around, worked with regular workers, did a lot of propaganda stuff, but mostly they were there to try to spur workers to actions and if workers actually did take action, then it could become of regional and national importance, allowing workers to come to these remote places and the central offices in Chicago and other regional offices to publicize the action.

And remote places these mostly were. After the failure of the Paterson strike in 1913, when it became clear the IWW did not have the resources or wherewithal to successfully organize eastern industrial workers, most of the union’s attention turned to the isolated mining and timber and agricultural camps. These were mostly in the West, but not exclusively. A place such as the Iron Range was technically not the West, but shared the isolation, corporate domination, and lack of options for workers that defined the copper mines of Arizona or the timber camps of western Montana.

Workers quickly created a list of demands. They didn’t just want an 8-hour day, they wanted that 8 hours to include the descent to and ascent from the mine. They wanted pay raises to $3.50 a day if the area of the mine where workers labored was wet, $3 if it was dry, and $2.75 for work on the surface. They wanted to be paid promptly and twice a month. Finally, they wanted the end of the contract labor system. That was super important for the obvious reasons that it was just about the worst labor system imaginable for the workers.

The mining companies completely refused to negotiate. Instead, they hired 1,000 armed thugs to guard their mines and intimidate the miners. It wasn’t too surprising then when one of the thugs killed John Alar outside the Oliver Iron Mining Company on June 22. This did open an opportunity for the IWW. Big public funeral marches was the kind of the thing the IWW did very well. For Alar, the IWW hosted a huge funeral with 3,000 marchers holding signs that read “Murdered By Oliver Gunmen.”

The mass funeral did put some extra heft into the strike, but that did not change the minds of the mine owners. They responded by getting the cops to arrest the leading IWW organizers, Carlos Tresca and Sam Scarlett and toss them into prison on bullshit charges of criminal libel. This only led to more violence. On July 3, there was a shootout in Biwabik between workers and the forces of order. In this case, workers killed a deputy sheriff names James Myron. A Finnish soft drink distributor named Tomi Ladvalla was also killed in the crossfire. This led to another roundup of IWW organizers. this time on murder chargers. The governor of Minnesota, J.A.A. Burnquist, completely siding with the companies, banned the use of pickets that kept scabs out of the mines.

This more or less killed the strike. The IWW did not have the kind of centralized resources for a sustained strike. This always plagued the organization. It had a few things it could rely upon–excellent organizers, great propaganda efforts, the commitment of members to show up in solidarity and flood prisons or work the picket lines. But it did not have the finances or personnel to hold up over the long run. To be fair, that wasn’t so different that more conservative unions at this time either. The difference was that the IWW valued the strike as the ultimate weapon of worker power, so it was tested more often in this way than most other unions were.

The IWW did everything it could. It sent more strike organizers, including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. But all its efforts could not overcome the massive power of corporate America working with the political system. Workers slowly started trickling back to work. On September 17, the strike officially ended. It was a total failure for the IWW. For the workers, it was slightly less of a failure, since the mine owners did slightly improve conditions in response, including some changes to the contract labor system, pay raises, and the 8-hour day. With the union defeated, all the IWW prisoners were released in December.

This is the 524th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.