Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,569

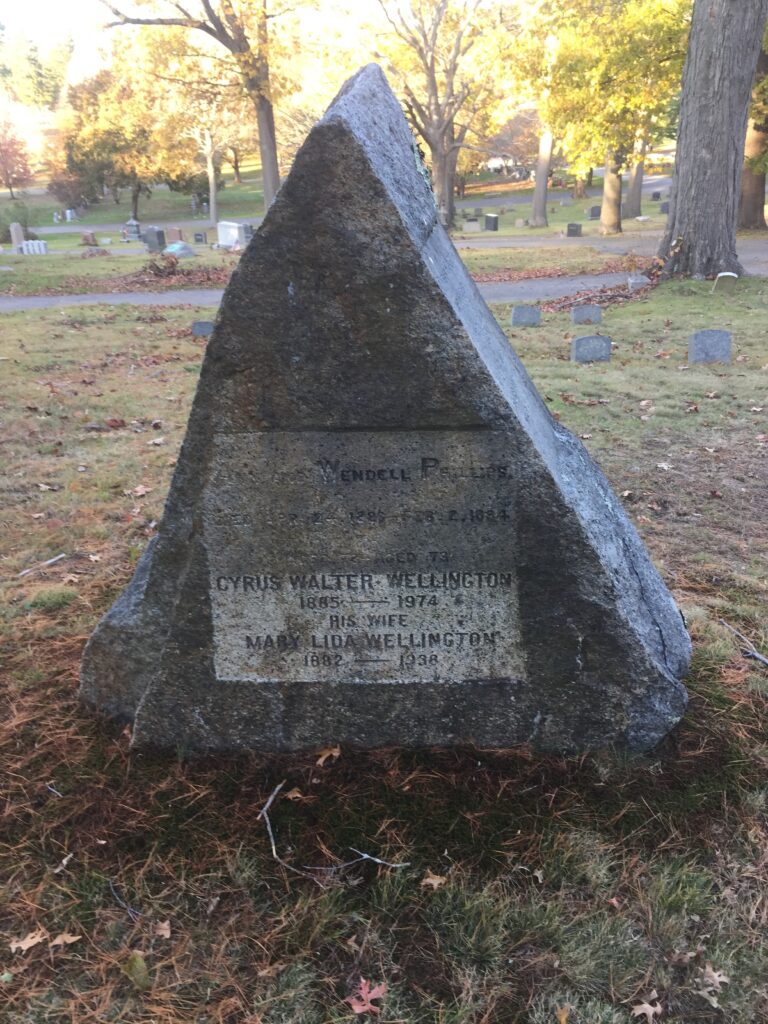

This is the grave of Wendell Phillips.

Born in 1811 in Boston, Phillips grew up as part of the long-standing Boston elite that went back to the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. He went to Boston Latin, then to Harvard, graduating in 1833. He passed the bar the next year and started practicing in Boston.

Phillips was interested in reform movements, but it was only in 1836 when he became a convert to abolitionism. This is an interesting story. He had come to know William Lloyd Garrison, who was fanatically anti-slavery. People think that abolitionism was a popular cause in the North. It was not. People saw Garrison as a freak and a traitor to the white race, whatever that meant at the time, which was definitely not the same for everyone. The Irish quickly adopted anti-Blackness as a way to rise in American society, but for many of the city’s elites, the Irish definitely weren’t white. In any case, that year, the British abolitionist George Thompson was scheduled to speak in Boston. abolitionist forces not only threatened to kill him, but offered a reward of $100 to the person who committed violence against him first. Thompson bailed. Garrison, who was scared of nothing it seems, agreed to step up instead. The anti-abolitionists kept up the prize money. Garrison was nearly lynched upon starting his speech. His head was literally in the noose before a bunch of the city leaders recruited some strong dudes to rescue him and place Garrison in jail, the only place he would be safe from the mob.

Well, Phillips saw this all happen from his window. He was absolutely disgusted. He probably was moving toward abolitionism anyway, but this clinched it. Other than Garrison himself, no one became more hardcore on opposing slavery than Phillips. A great public speaker, he could move audiences on issues of race like few others. Maybe Frederick Douglass, once he became more known, but within the white community, Phillips was probably the best orator. And Phillips was absolutely uncompromising. He came to believe that the reason for all the nation’s problems was racism and he demanded that whites separate themselves from all aspects of slavery. So he was a big proponent of the free produce movement, which was basically trying to boycott any product made with any slave labor, meaning all cotton at the very least, but also sugar and other plantation crops such as tobacco. That giving up sugar and tobacco were common things in some of the other reform movements of the era, such moves might have received broader acceptance than you might expect.

Now, Phillips argued as early 1845 that the slave states should secede from the union. This I think was an error. I always have failed to see how it would help the vast numbers of poor people and people of color if Alabama or Arkansas seceded from the union again, but even today some liberals do love to make flippant comments about letting them go or wishing we hadn’t fought the Civil War to get these states back or whatever. There are a lot of good people in these states. And I don’t see how in 1845 it was going to make the United States any purer to promote the slave states just leaving the country. How many slaves was this supposed to help? So I’ve found these statements a bit cheap and empty. But Phillips would continue with them all the way up to the Civil War, including when the South was actually seceding.

In the late 1830s, Phillips and his wife spent a couple of years traveling around Europe. One of the things they wanted to do was to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840. The U.S. had sent a women’s delegation, which included Phillips’ wife Ann. But the Europeans hadn’t expected anything so outrageous as women to show up. I mean, we are a serious movement here, amirte! So the women were rejected. Phillips to his credit, and because his wife demanded it of him, led the charge to have them seated. A compromise was created that allowed the women to attend but not speak. For a lot of these women, this moment was when they realized a separate women’s rights movement needed to form.

Phillips put his body where his mouth was too. He was active in the attempt to free Anthony Burns from slavecatchers and the government in 1854, an event that basically made the Fugitive Slave Act null and void in Boston. When the Civil War finally happened, other than wanting the Confederacy to just go away, he figured that if the U.S. was going to fight over this, the first thing it needed to do was to end slavery. As such, he lambasted Abraham Lincoln for moving too slowly on the issue. In fact, in 1864, well after the Emancipation Proclamation, as limited as that foundational document of American freedom really was, Phillips refused to support Lincoln’s reelection because he was not doing enough for Black rights. Even Garrison voted that year for Lincoln.

Phillips also dedicated himself strongly to women’s rights, unsurprisingly for a man who had infuriated much of the European and American anti-slavery elite by demanding women’s participation in the movement. He wrote extensively in Garrison’s The Liberator about the need for women’s equality, including property rights within marriage, as well as of course the suffrage. He spent much of the 1850s working closely with Lucy Stone on these issues and was a real leader, even among reformist men, many of whom were cool with a lot of reforms, but women’s rights???

After the Civil War, Phillips argued for a vigorous Reconstruction. He was a big proponent of explicit voting rights for the freed slaves, saying they could never secure their freedom without them. He loathed Andrew Johnson, unsurprisingly. Phillips also believed strongly in the redistribution of southern plantations to the ex-slaves. But that was not going to get much traction in a society where for many Republicans, not respecting the principle of private property (at least when it wasn’t humans) was a more fundamental crime than slavery. There would be no land redistribution programs in Reconstruction and what did exist, through Sherman’s Special Order No. 15, would repealed. And lo and behold, the freed slaves did not gain economic emancipation, as Phillips would have predicted.

Phillips was also a leader on Native rights. This was unusual. Plenty of abolitionists were completely pro-genocide when it came to the tribes. That was not Phillips. He openly accused Phil Sheridan of committing genocide in the West (he didn’t have that word in his vocabulary, but that is effectively what he described). He wanted the military out of the reservation system entirely. He even helped Grant pick more appropriate Indian agents, though to say those appointees were a mixed bag is a huge understatement. He also set up talks for Native leaders to explain the plight of their people to white audiences in the East.

By the 1880s, Phillips heart was giving out. He died in 1884, at the age of 72.

Wendell Phillips is buried in Milton Cemetery, Milton, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other abolitionists, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Bronson Alcott is in Concord, Massachusetts (surprised I haven’t been to this grave) and Arthur Tappan is in New Haven, Connecticut. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.