People’s History of the Marvel Universe, Week 20: The (Mutant) Registration Act(s) Analyzed

In his sixteen-year tenure of the X-line, Chris Claremont put his own spin on the mutant metaphor any number of ways, but one of the longest-lasting and most influential has been the idea of a Mutant Registration Act. In the original Days of Future Past storyline, Claremont first mentions the Mutant Control Act passed by a “rabid anti-mutant candidate…elected president,” as a reaction to the assassination of Senator Robert Kelly.

In this issue, Claremont doesn’t mention what the provisions of the Mutant Control Act were, only that they were struck down by the relatively liberal Burger Court, presumably on 14th Amendment Equal Protection grounds. The Supreme Court’s thwarting of populist overreach unfortunately gives rise to the dark future of Earth-811, as the new president authorized Project Wideawake to send the Sentinels to hunt down mutant-kind, only to find that (once again) the Sentinels decide to accomplish this by conquering humanity and installing an apartheid state to root out carriers of the X-gene from the human population.

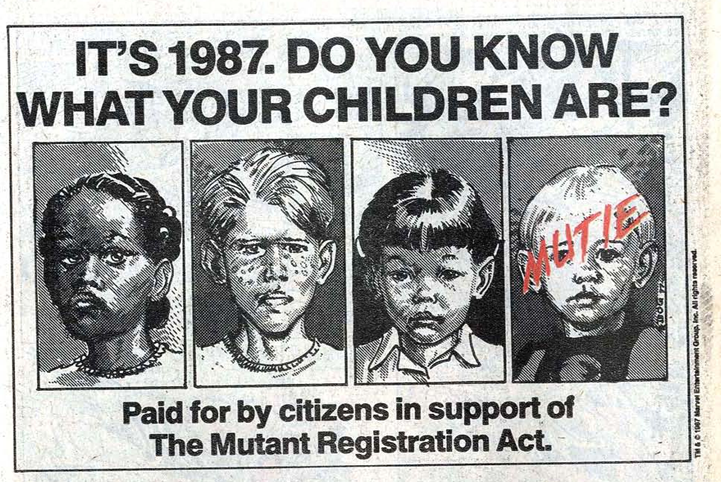

It’s worth taking a moment to parse the iconography of this populist anti-mutant movement, enshrined in the slogan “America! It’s 1984! Do you know what your children are?” Deliberately evoking the public service announcements that were introduced to back up youth curfews in Los Angeles in the 1960s that asked parents “it’s 10pm: do you know where your children are?,” this line turns the child-centric paranoia of the moral panics of the 1980s like the McMartin day care scandal or the Satanic Panic on their head; instead of children being the threatened object of outside threat, here the children are the subject of threat, the threatening outsider within. Moreover, this line clearly captured the imaginations of Claremont and Marvel editorial, because in X-Men #223 they took the unusual step of reproducing that line in an in-universe advertisement in the issue’s back matter:

This ad is worthy of some close analysis: by displaying an African-American child and an Asian boy alongside two fair-haired white children, the ad’s designers emphasize that mutant status exists on a parallel plane to race. While the mutant metaphor often is used to equate mutancy to real-world minority statuses, here it’s being demonstrated that that metaphor only goes so far. Next, by scrawling the racial slur of “mutie” across the face of an innocent child, the power of anti-mutant bigotry to stir up fear and hatred of even the most innocuous of targets is emphasized. Finally, and most importantly for the purposes of this essay, by having the in-universe commercial be “paid for by citizens in support of The Mutant Registration Act,” the ad’s creators tied together the Mutant Control Act from the dark future of Earth-811 and the Mutant Registration Act introduced by Senator Kelly in the present of the main 616 timeline in the wake of Days of Future Past.

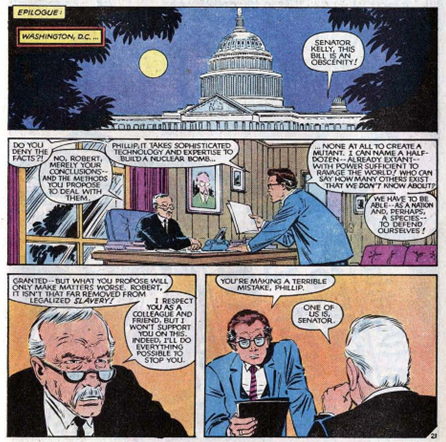

Speaking of which, we see the “Mutant Control Affairs Act” introduced in the final pages of X-Men #181, which features a debate between Senator Kelly and an older, mustachioed Senator. This debate gives us one of the longest discussions of the Mutant Registration Act that Chris Claremont featured in the pages of X-Men.

As we can see from this dialogue, there’s not a lot of detail about concrete provisions of the Mutant Registration Act and, as we’ll see later, this vagueness is a deliberate choice by Claremont to suggest the broad strokes of discrimination while leaving the details up to the individual imagination. We know that Senator Kelly remains as concerned about human supremacy as he was back in Days of Future Past – although the national security angle is new (probably relating to his partnership with the new administration’s Project Wideawake) – and its atomic undertones are oddly reminiscent of Silver Age X-Men. The closest we get to specifics is Senator Phillip’s description of the MRA as not “far removed from legalized slavery.” As I’ll discuss in more detail later in the essay, this seems to be code for provisions relating to a special military draft– reminiscent of how the human supremacist state of Earth-811 used the Hounds to hunt down other mutants – which would have particular resonance only a decade after the end of the Vietnam War.

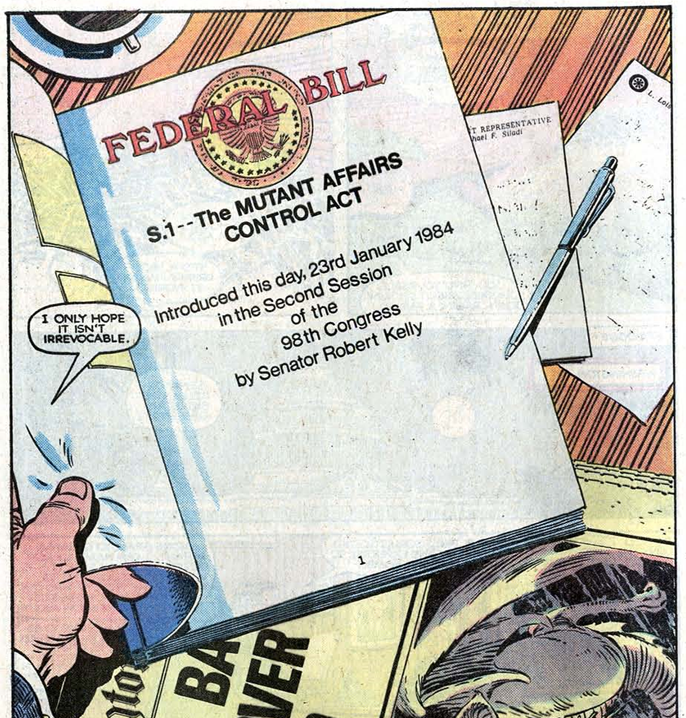

One piece of specific evidence about the bill that we do get is a half-page panel where John Romita Jr. gives us the title page of the actual legislation:

It’s a particularly ominous sign that the “Mutant Affairs Control Act” is titled as S.1; in both the House and Senate, early numbers in each legislative session are reserved for marquee bills that majority leadership want to highlight as a major priority for that session as a standard bit of legislative public relations. This is an early signal that the Mutant Registration Act will become law despite the best efforts of Senator Phillips and others like him. Another nice little touch is the effort to maintain verisimilitude: the second session of the 98th Congress really did begin on the 23rd of January, 1984, giving the impression that this is all happening in the present – X-Men #181 hit newsstands in early February 1984 – something that Claremont did quite a bit in the days in which Marvel Comics was a bit more “the world outside your window” than sliding timescales.

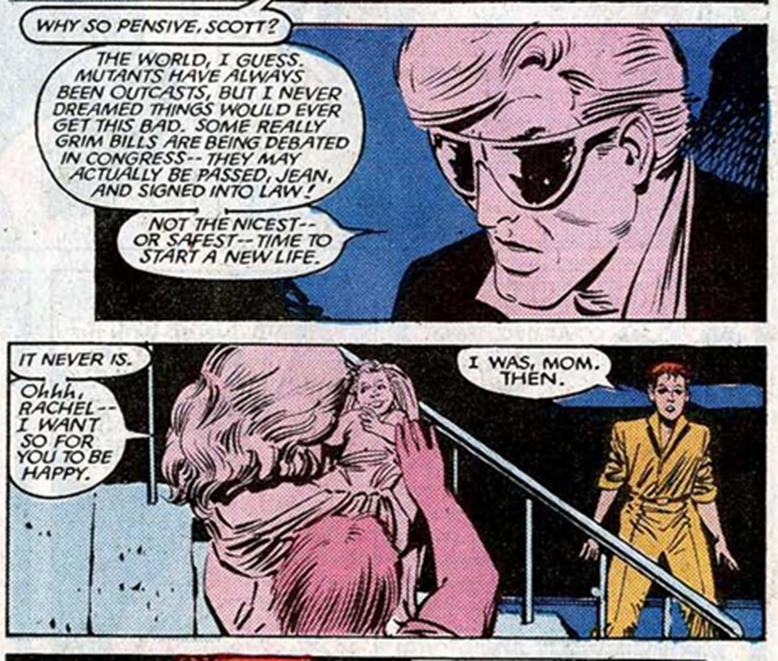

However, that’s really all we get on the specifics of the Mutant Registration Act. Rather than spend page space laying out the details of fictional legislation, Claremont instead used the Act as a recurring background element that could highlight aspects of characterization and plot development as needed. For example, Claremont used the MRA to emphasize Rachel Summers’ role as a time-traveler from a different future:

As we can see, Claremont is primarily interested in using the Mutant Registration Act as a synecdoche for the dystopian future of Earth-811: in the first panel, Claremont has the news broadcast end the moment as it’s about to describe the “draconian provisions” of the bill, partly because he wants to leave those details up to the reader’s imagination, but mostly because the important thing about this story beat is that the newly-arrived-in-616 Rachel recognizes the proper name of the legislation from her own past, raising the specter that the X-Men’s sacrifice in Days of Future Past failed to avert the Terminator scenario which is inevitably going to come to pass. In the second panel, the psychic impression of Scott Summers merely refers obliquely to “grim bills” without describing what those bills are, because what’s important in this scene is how Rachel associates those bills with a moment of fragile (and ultimately, futile) hope for her childhood, emphasizing the way she feels torn between the hope that the Sentinel takeover has been prevented and the somber realization that this may mean that her birth, and thus her identity as a “real” person, may have been forestalled by the rewriting of the timeline.

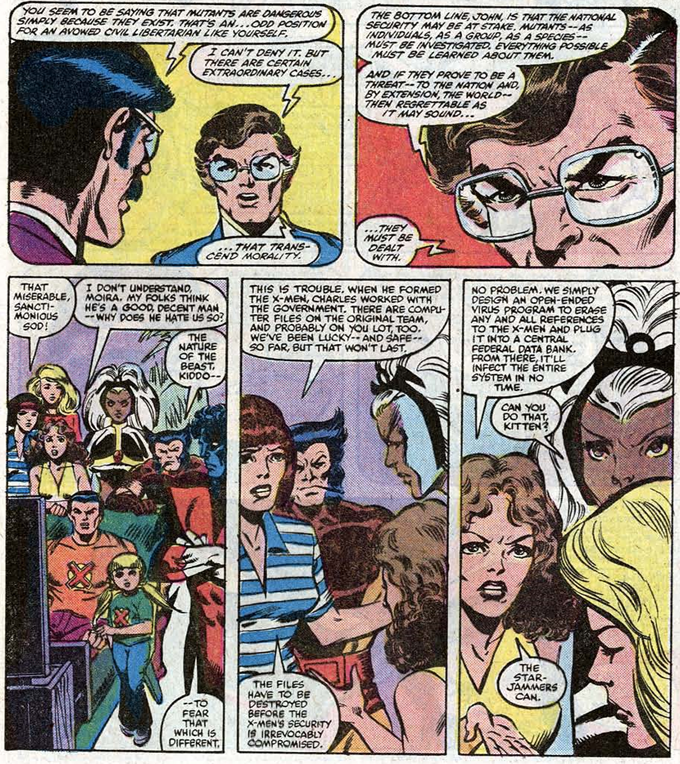

More commonly, Claremont used the Mutant Registration Act as a motivating force for plot, animating events across multiple issues, as part of his trademark style of gradually developing stories across years of continuity. In X-Men #158, the pending MRA prompts the X-Men to repent of their days providing information on mutants to the FBI by raiding the Pentagon to purge that data from government computers, thematically drawing a bright line between the more assimilationist politics of the Silver Age X-Men and the more radical direction that Claremont would be taking the book in the 1980s.

While the X-Men are successful in purging their data from Pentagon servers, impeding the efforts of the Federal government to surveil mutant citizens, the resulting melee between the team, Rogue and Mystique, and the U.S military begins the process that sees the X-Men labelled as outlaws by the U.S government – an important transition that Claremont will use to guide the book through the next several years. For example, in #182, Rogue attempts to rescue Colonel Mike Rossi from Hellfire Club double agents on a SHIELD Helicarrier, which gets misinterpreted as an unprovoked assault that prompts an APB[1] from Nick Fury for Rogue’s detention or execution. This then leads to issue #185, where Valerie Cooper and Henry Peter Gyrich – the chief Federal enforcers of the Mutant Registration Act – use the opportunity afforded by the APB to go after Rogue with an experimental weapon designed by Forge that removes mutant powers (inadvertently depowering Storm in the process). In #193, the Hellions provoke an incident at Cheyenne Mountain that leads to a “nation-wide manhunt for the mutants known as the Uncanny X-Men.” In this fashion, the X-Men gradually slide from a standard superhero team (albeit one devoted to protecting a world that hates and fears them) to becoming a group of outlaws, on the run from Federal authorities that is both driven by and acts as further justification for official anti-mutant prejudice.

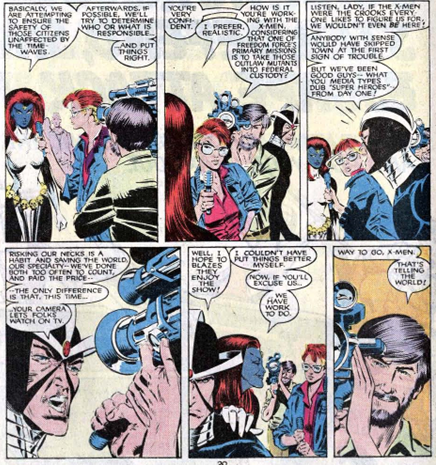

To the extent that Chris Claremont devoted an entire arc to the Mutant Registration Act, it would come in the 1988 crossover event “Fall of the Mutants.” While the climax of the event is focused on the supernatural – the scheming and intrigue of demons and goddesses, interdimensional portals opening in the skies above Dallas, death and resurrection – one of the major throughlines is the Mutant Registration Act and the Federal government’s efforts to enforce it against the X-Men. It begins with X-Men #206, where the X-Men find themselves the unlikely heroes of San Francisco after having defended the city from Omega Sentinels and the Beyonder. While recuperating from those fights, the X-Men find themselves coming under attack from Freedom Force, a super-powered Federal task force created by Special Assistant to the National Security Advisor Val Cooper[2] to enforce the Mutant Registration Act.

In another sign of how mutant politics were shifting under Claremont’s pen as he moved towards the end of his first decade on the book, Freedom Force was formed out of Mystique’s Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, so that we have a group of former mutant radicals who once staged terrorist attacks on the U.S Capitol turning quisling to protect themselves from human authorities while the X-Men make the transition from former collaborators with the national security state to fugitives living underground. In the ensuing brawl, the X-Men find themselves firmly on the back foot, thanks in no small part to Freedom Force’s cavalier willingness to inflict collateral damage on residential neighborhoods of San Francisco. Ultimately, our heroes are rescued by the unlikely intervention of the San Francisco Police Department, who act to stop the fighting and the property destruction:

Especially in the contemporary context of the late Eighties, this confrontation between agents of the Federal government – visually if not textually identified as the Reagan Administration in X-Men #201 – and officers of the city of San Francisco had real-world political resonance. At this time, the public perception of pre-tech boom San Francisco was that of a center of left-wing politics and especially a center of the gay rights movement and very much diametrically opposed to Reagan’s conservative politics and his administration’s vocal hostility to the LGBT movement during the AIDS epidemic. Notably, here we see Lieutenant Morrel of the SFPD acting as the voice of civil libertarianism, emphasizing the need for warrants, documentation of presidential pardons, and other accoutrements of due process against Freedom Force’s paramilitary flaunting of constitutional rights.

The thread is picked up again in X-Men #223, where once again the X-Men find themselves in San Francisco, where “people here don’t seem to mind the X-Men’s presence – they consider us heroes.” In this issue, we see Freedom Force expanding by drafting the heroes-turned-murderous-vigilantes Super Sabre, Crimson Commando, and Stonewall. During the ceremony where these three receive their presidential pardon, Destiny receives a vision that Rogue and the “X-Men are going to die!” This prompts Mystique to choose further confrontation with the X-Men on the grounds that if Rogue is arrested under the Mutant Registration Act, she won’t go to her prophesied death in Dallas.

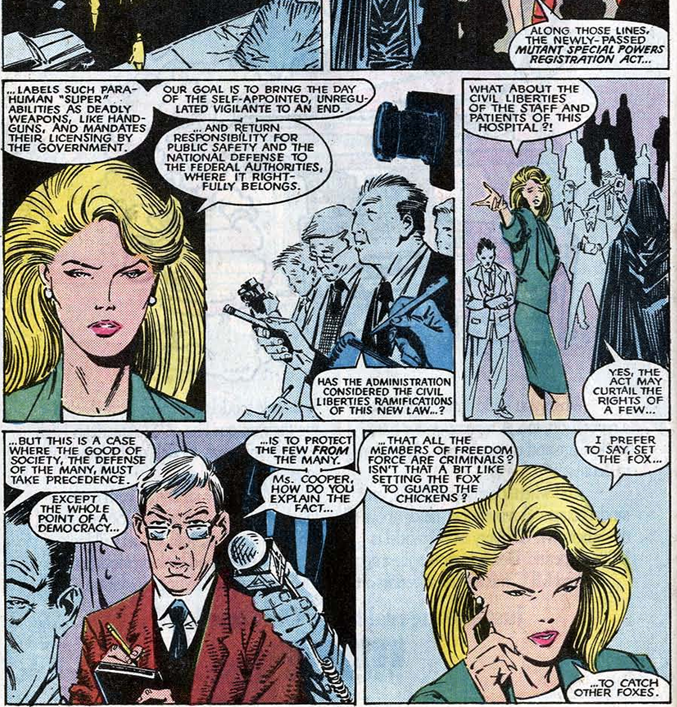

In the next issue, we see Val Cooper and Freedom Force return to San Francisco “hunting for X-Men’s scalps,” posing both a physical and political threat to the countercultural heroes of the City by the Golden Gate. We see this most clearly as Valerie Cooper mounts a press conference in front of a damaged San Francisco hospital to announce the formation of Freedom Force and the passage into law of the “Mutant Special Powers Registration Act.”

This sequence is particularly significant because it introduces the parallel between superpowers and handgun licensing – a real-world political analogy that will be alluring for Marvel creators for decades, as we’ll discuss later. Here, though, the handgun issue is treated as a relatively minor element compared to the broader question of civil liberties, and the extended discussion of whether the “good of society, the defense of the many” takes precedence over the rights of the minority. This is a good example of how the mutability of the mutant metaphor continued during the Claremont years; rather than making a more concrete analogy to a real-world minority as he does in other places (such as in “God Loves, Man Kills”), here the “few” whose rights are being curtailed by the Mutant Registration Act could be any minority facing official discrimination from the “many.”

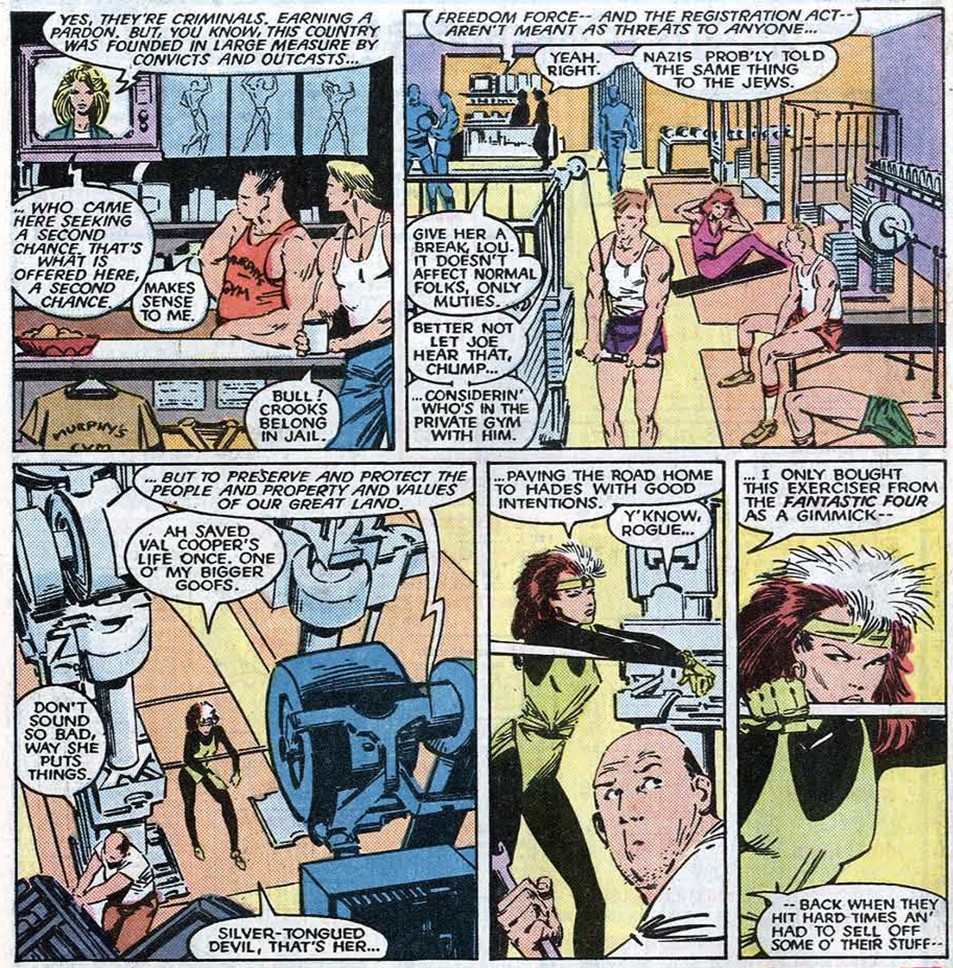

On the following page, we see the impact of Cooper’s speech on the body politic, as a number of patrons of a San Francisco gym where Rogue is exercising debate the issue:

One of the lesser talked about aspects of Chris Claremont’s writing is the skill with which he can quickly sketch background characters to give a picture of the internal life of the “man on the street.” Here, we see a public divided on their attitudes toward the Mutant Registration Act: one man raises the historical parallel of the Holocaust (a frequent thematic angle in Claremont’s writing) to frame the MRA as a potential genocidal threat. His interlocutor denies the threat, distinguishing between racist threats to “normal folks” and the legitimate oppression of “muties,” again showing how Claremont can turn on a dime between leaning on the parallels to real-world bigotry that the mutant metaphor was based on and pointing out the ways in which in-universe minority politics might fail to intersect.[3]

On the next page, we see a disguised Mystique arrive to clandestinely warn Rogue – a sign that Mystique’s participation in Freedom Force is very much an act of personal survival rather than a sign of an ideological shift, as Mystique is very much using the government to further her own interest – that the X-Men are going to die in Dallas, telling her to leave them so that “you won’t share their fate.” As in any proper tragedy, this warning falls on deaf ears as Rogue refuses to abandon her comrades in arms, choosing instead to go with them to Dallas to confront the threat posed by the Adversary. Before they can make it into Forge’s Eagle Plaza tower and their eventual confrontation with the embodiment of cosmic chaos, the X-Men once again find themselves by Freedom Force and the threat of imprisonment under the Mutant Registration Act:

In addition to providing an excuse for super-heroic fisticuffs, the confrontation gives a rare instance where Claremont provides some insight into what the Mutant Registration Act specifically does – clarifying that the MRA criminalizes using mutant powers rather than “simply being born a mutant.” At the same time, Claremont has Havok immediately question the “credibility” of this statement. After all, the Registration Act already criminalizes mutant citizens by forcing even children[4] to register with the government when their human peers don’t have to. Moreover, many mutants have “always on” powers that they don’t have a choice whether to consciously activate or keep hidden, making Mystique’s distinction between the two as one without a difference.

Through their trademark collaborative use of mutant powers, the X-Men manage to fight their way past Freedom Force and into Eagle Plaza, activating the Adversary’s trap which opens an inter-dimensional portal in the skies above Dallas that begins summoning threats from the prehistoric time of dinosaurs all the way to the Wild West of Texas’ past. Witnessed by real-life NPR reporters Neal Conan and Manoli Weatherell, the X-Men answer the call to defend the world from the supernatural threat pouring through this rip in the night sky above Dallas:

This scene shows the continuation of the X-Men franchise’s fascination with the role played by mass media in the propagation of – or challenge to – popular prejudice and mob panics. Here, Conan and Weatherell act as ideal journalists, challenging the statements of Federal authorities and raising uncomfortable questions about Freedom Force’s role in enforcing the Mutant Registration Act against superheroes presently engaged in self-sacrificing defense of civilian communities. More importantly for the purposes of this essay, they amplify the voices of “outlaw mutants” who are otherwise excluded from the mainstream, allowing them to spread an anti-MRI message directly to a mass audience.

And that’s really where the Mutant Registration Act plot line ends in Claremont’s run, with the X-Men dying to save a world that hates and fears them, only to be reborn by the grace of a goddess figure who grants them invisibility from the technological eyes of the surveillance state and transports them to the Australian Outback where they can continue their lives as outlaw heroes free from the efforts of the U.S government to arrest them. It’s a momentous change of status quo for the X-Men themselves, but as regards the MRA itself, there’s not the kind of climax where the reader sees this vile legislation struck down by the Supreme Court (as happened in the Days of Future Past storyline) or repealed by Congress in light of the X-Men’s actions in Dallas (or X-Factor saving New York City from Apocalypse over in their book).

It’s possible that this is intended to be some kind of statement about the possibilities (or lack thereof) of achieving progress for visible minorities in American society. If that’s the case it’s very much a statement that exists in the absence of the text rather than in its presence, because Claremont will move on to new plots that will explore other angles of the mutant metaphor – as we’ll discuss in future installments of the People’s History of the Marvel Universe.

But just because Chris Claremont had tired of the Mutant Registration Act as a theme doesn’t mean that the Marvel Universe was done with the idea. A year after Claremont concluded the “Fall of the Mutants,” his close friend, colleague, and sometimes collaborator Walt Simonson would take up the concept in Fantastic Four #335-6, a two-issue arc devoted to exploring the political implications of Registration Acts in the Marvel Universe:

In these issues, the Fantastic Four travel to Washington D.C to testify in front of a House committee that is holding hearings on a proposal to enact a Superhuman Registration Act. The bulk of the first issue sees the First Family largely sitting in the audience as a series of witnesses testify in front of the committee for and against the legislation. The first to testify before the committee is a “General Neddington,” who’s there to provide the views of the Pentagon:

Here, Walter Simonson makes explicit what we’ve previously seen only alluded to in Claremont’s and Louise Simonson’s[5] writing – the purpose of the Superhuman Registration Act is to draft superpowered people into the U.S military, not only to defend the country “in times of crisis” but also to ensure U.S dominance in “the balance of military power in the world.” In another example of how Simonson brings political subtext into text, Simonson also has an unnamed black Congressman bring up the real-world racial disparities in military service in the Vietnam War. This history was very much in living memory in 1989 – after all, the military draft had been ended in 1973 and then re-instated quite recently in 1980, when Jimmy Carter had re-instated the requirement to register with the Selective Service Act as a response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. As we’ll see later, the politics of the draft were very much on Simonson’s mind here.

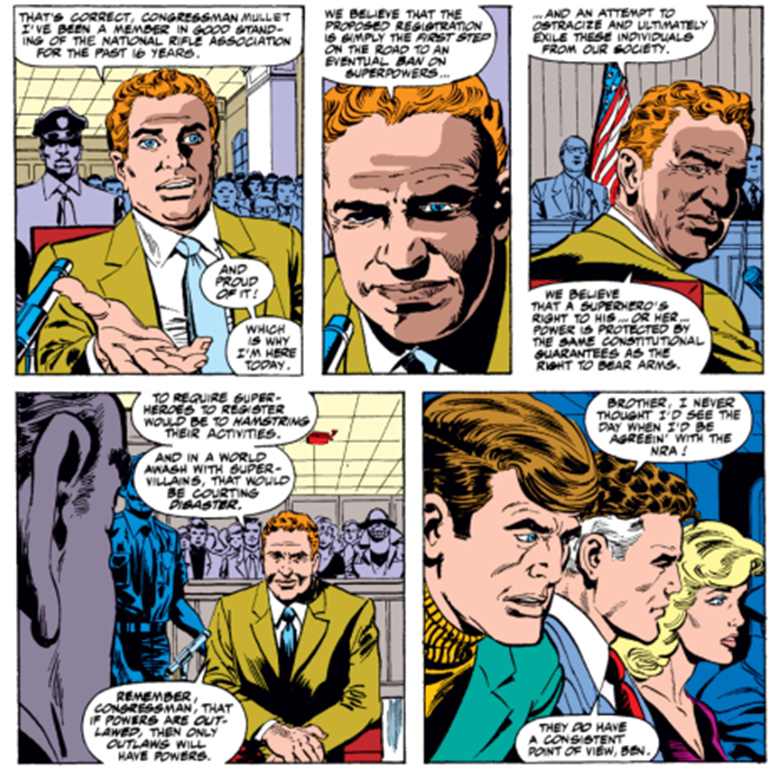

From Cold War politics and the legacy of the Vietnam War, Simonson takes up another of Claremont’s themes – namely, the parallel between Registration and the licensing of firearms:

Building off what was a passing reference in Claremont’s work, Simonson puts the analogy of gun control front-and-center by having an NRA spokesman testify before the committee. (Simonson shows his research by paraphrasing the National Rifle Association’s catchphrase that “if guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.”) Here, the NRA are an interested party because they believe that the 2nd Amendment’s right to bear arms applies to superpowers as well as firearms. By extension, the NRA sees a Federal attempt to register superpowered Americans as the “first step on the road to an eventual ban on superpowers” – and logically fears that the same thing might happen to gun owners – just as the real-world NRA catastrophizes modest efforts at gun control as mass confiscation.

Having a notably partisan conservative organization like the NRA testify on behalf of the Fantastic Four must have produced a certain amount of tension for both Simonson himself and Marvel as a whole, given the historic tendency of its creative workforce towards somewhere between the center-left and the left (depending on which generation of creators one is talking about). A good deal of – as the People’s History of the Marvel Universe has demonstrated, inaccurate – ink has been spilled about the supposedly inherently fascistic politics of superhero comics, but the more accurate label is that vigilantism has been part of superhero comics’ DNA from the beginning. If a superhero is anything else, they are ultimately a costumed adventurer who steps outside of their everyday life that’s sanctioned by society in order to exercise powers that are normally monopolized by governments. To an extent, there remains something of an uncomfortable parallelism between the NRA’s “good guy with a gun” mythologizing around crime and the tradition of costumed crimefighters. Simonson vocalizes the tension he’s feeling through Ben Grimm, the Lower East Side-born Jewish superhero who more than any other character symbolizes the cultural and political wellspring from which Jack Kirby’s decidedly left-wing approach to superheroism always drew inspiration. For the ever-lovin’ blue-eyed Thing, having to be on the same side as the NRA is a “revoltin’ development” – which gives a certain amount of consolation to liberal readers.

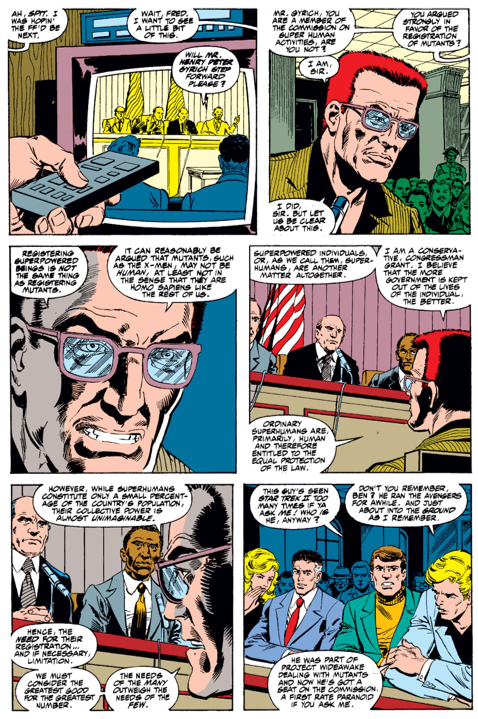

After these two witnesses have set out the real-world political implications of the Superhuman Registration Act, Simonson dives into the in-universe politics, and in the process establishes a vital link between his SRA and Claremont’s Mutant Registration Act by using a character who just so happens to straddle the divide between the X-line and the broader Marvel Universe:

Contrary to what many writers in both fandom and academic circles have argued, Gyrich’s testimony demonstrates how the mutant metaphor works best in the broader context of the Marvel Universe. Henry Peter Gyrich opposing the registration of super-humans while supporting the registration of mutants (presumably a sign that he’s adopted the party line after the events of X-Men #176) is not only a perfect example of the hypocrisy and irrational double-standards inherent to bigotry, but also a straightforward statement of that prejudice. To Gyrich, it is unacceptable for the Federal government to register super-powered humans because they are “entitled to the equal protection of the law,” but acceptable for the Federal government to do the exact same thing to super-powered mutants, because they’re not human in his eyes and therefore aren’t entitled to constitutional rights under the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment.

In discussing the concept of a law “restricting a limited section of the nation’s population,” Simonson shows an impressive level of research for a superhero comic. When Gyrich responds to questioning the constitutionality of the Superhuman Registration Act by bringing up the example of women not having to register with the Selective Service System, he’s actually referring to what was then very recent developments in constitutional law. While the draft was ended in 1973 due to its deep unpopularity in the midst of the Vietnam War – which we’ve already seen very much on Simonson’s mind – this state of affairs would only continue for a few years. In a response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, President Carter re-established the draft in 1980. During the Congressional debates over the re-authorization of the draft, the issue of whether women would be subject to registration was raised, in light of the ongoing national debate over the Equal Rights Amendment and the broader acceptance of the principle that gender discrimination was unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. A year later, in Rostker v. Goldberg, the Supreme Court was asked to rule on this point when a group of draft resisters challenged the draft on the grounds of gender discrimination, ruling 6-3 that the Selective Service System’s male-only registration could stand because of the armed service’s bans on women serving in combat roles.[6]

Finally, Henry Peter Gyrich’s testimony makes it very clear that both the Mutant and Superhuman Registration Acts’ purpose is to put superpowered beings under government control, so that they can be used as agents of oppression. While he speaks of “super-human individuals or groups of an altruistic nature” being merely “persuaded to aid the government in tracking down and registering any individuals or groups who refused to comply,” Simonson throws doubt on the voluntary nature of this assistance, implying that superheroes would be forced into service under the Superhuman Registration Act’s conscription clause. More troubling, Gyrich demonstrates a consistent inconsistency as a supposed conservative who’s concerned about the rights of the individual opposed to the interests of the state when he opposes the extension of “the same constitutional guarantees that the police must follow” to these new federal agents. In a display that again echoes the real-world stance of “law and order” conservatives on police brutality, Gyrich sees any limitations on both superpowered federal agents or human police officers as “tying the hands of law enforcement” and “aid[ing] the criminal element.” By implication then, the Superhuman Registration Act would lead to a lawless paramilitary force completely unanswerable to any authority other than a “human czar” of “a bureau of superhuman affairs” – much in the same way that Freedom Force demonstrated a complete disregard for civil liberties while enforcing the Mutant Registration Act.

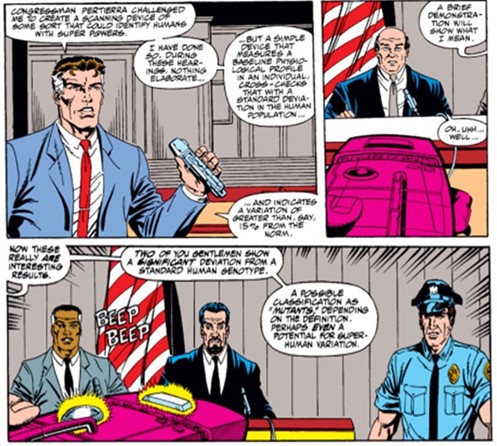

In between fist-fighting supervillains who’ve showed up in trench coats and fedoras to infiltrate the Congressional hearing, the Fantastic Four get their chance to testify against the Superhuman Registration Act. Their arguments come from a number of different political angles – Sue Storm talks about wanting to ensure that her son grows up in a free country, Johnny Storm points to the practical impossibilities of registering “Dr. Doom or Annihilus,” and good liberal Ben Grimm decries the contrast between the ease with which “crooks can go out and buy assault rifles” and the proposed restrictions on the superheroes who try to stop them. As we might expect from the FF, though, the majority of page space is given to Reed Richards, who delivers a filibuster-worthy speech that spans issue #335 and #336. Mister Fantastic presents many arguments against the Superhuman Registration Act – one of the more troubling one being that non-superheroes lack the ability to second guess split-second decision making by experienced superheroes, which echoes uncomfortably with defenses of police shootings – but the one that ultimately convinces the Congressional committee to shelve the SRA is a perfect blend of politics and superhero science-fantasy:

Ultimately, what gets the Congressional committee to shelve the Superhuman Registration Act is an argument centered on the impossibility of defining who is a super-human and who isn’t – because people’s abilities and genetic heritage vary so much from individual to individual, an arbitrary cutoff like a “variation of greater than, say, 15% from the norm” would sweep up many false positives, such that the discriminatory impact of the SRA would be felt by Congressmen themselves. Taken together, Claremont and Simonson’s work is a classic case of a slippery slope argument applied to civil liberties – the denial of the rights of any minority becoming a precedent that creates a precedent for further authoritarian encroachment onto the rights of increasingly larger segments of the population, eventually ending in a general tyranny.

This all must sound eerily familiar to people who were reading Marvel comics circa 2006, when Mike Millar was handed the reins to a line-wide crossover in Marvel’s Civil War, which likewise centered on the Federal government passing a Superhuman Registration Act. Despite the several decades between the work of Claremont and Simonson and that of Millar, there’s more than a little bit of thematic and rhetorical overlap between them: we see similar analogies to gun control and the draft, similar debates about individual agency and vigilantism versus collective security and democratic legitimacy, and even similar mentions of the Mutant Registration Act as a model for official discrimination that’s still floating around out there in the Marvel Universe, still on the statute books ready to be picked up by forces in power.

When it comes to the political stance taken by the creators, however, we see a clear difference. Both Claremont and Simonson make it quite clear that registration is an unjust act of oppression that exists for the protagonists to struggle against. By contrast, putative leftist Mark Millar was so convinced of the correctness of the Pro-Registration side of the debate that, in the development process, he swapped the position of Captain America and Iron Man as leaders of the opposing camps. Millar’s logic was that Marvel couldn’t maintain the “choose a side” fan engagement that would be key to the crossover’s success, because it would be self-evidently obvious to everyone that the Pro-Registration side was right if it was led by a pillar of moral authority like Steve Rogers. (Full disclosure: I’m basing my claim for this on my memory of having read that the swap happened during development, but I can’t find the article that I originally read. Feel free to disregard this point.)

Here is where I think we can see the broader cultural impact of 9/11 on the politics of the Marvel Universe: on paper, a story in which a horrific tragedy is turned into a rhetorical bludgeon in order to justify the radical transformation of the status quo, and in which the Superhuman Registration Act, like the Patriot Act, becomes a mechanism for the destruction of civil liberties all the way up to indefinite detention without trial in black site prisons, would seem to be a powerful critique of the War on Terror. But while the creators who were brought in to write the tie-in issues did advance that kind of criticism, Millar’s main event book continued to present the actions of Tony Stark and Reed Richards as the wise decisions of enlightened futurists that was making the United States a safer, happier place – culminating in the thuddingly obvious visual symbolism of Captain America getting tackled by a group of NYC first responders at the height of his duel with Iron Man.

So after all of that, what is a Registration Act? Beyond the specific details of fictional legislation that obsess a public policy nerd like me, I think we can think of it as a kind of narrative mirror that comic book writers can hold up to see the world around them and the place that their genre has in it. At the same time, it’s not a device that should be used cavalierly as an excuse to bang action figures together; the way that it conjures allusions to real-world politics make it far too charged for that.

[2] Valerie Cooper is introduced in X-Men #176, where she leads a White House briefing on the national security threat posed by mutants like Magneto. While Cooper touches on the biological metaphor of the Cro-Magnon and the Neanderthal, she pivots from there to discuss the mutant threat from the perspective of international relations. As Valerie sees it, the existence of mutants means that “the virtual monopoly of super-beings…once enjoyed by the United States no longer exists.” Because of the willingness of the Soviet Union to recruit mutants into the Soviet Super-Soldiers, she argues that “mutants pose a clear and present danger to our country.”

Surprisingly, Henry Peter Gyrich (last seen heading up Project Wideawake, the Federal initiative to recreate the Sentinel program) challenges Cooper’s proposal to “fight fire with fire, counter[ing] foreign mutants with some of their own” on the grounds that Federal recruitment of mutants into the armed services would convince Magneto that his fears that “out of greed, humanity will use mutants – enslave them – and then, out of fear, destroy them” are coming to pass, risking an escalating confrontation with the Master of Magnetism.

While this scene predates the Mutant Registration Act, it’s nonetheless an important bit of context for understanding the goals and mechanisms of the MRA. While the main X-Men book itself doesn’t make mention of the Mutant Registration Act involving the forced conscription of mutants outside of Senator Phillip’s vague analogy to slavery, we do get an important clue in X-Factor #33. In that issue, the group of mutant supervillains known as the Alliance of Evil go on a rampage in front of Trish Tilby’s television cameras in order to protest their arrest and imprisonment under the Mutant Registration Act. Specifically, the Alliance of Evil mentions that they refuse to join “Uncle Sam’s mutant army” – implying that one of the major aspects of the MRA is to use forced registration, surveillance, and the threat of imprisonment to draft mutants into becoming unwilling soldiers in the national security state.

[3] Similarly, in X-Men #223, Claremont breaks away from the main action of the book to show an interlude in a Queens bar where a white working-class character defends himself against charges of anti-mutant racism by pointing to his close friendship with a black working-class character, arguing that “we ain’t the same color, but we’re still people.” By contrast (he explains), mutants are inhuman freaks who should be euthanized at birth by their own parents to prevent an “abomination” from walking the streets. In this instance, Claremont is arguing that anti-mutant prejudice exists at right angles to anti-black racial prejudice – something of a departure from his stance in “God Loves, Man Kills.”

[4] See X-Factor #33.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Interestingly, this constitutional position has continued to this day, despite the U.S military having eliminated gender restrictions on combat duty in 2015. In 2019, a District Court judge ruled against the Selective Service System under the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment, only to be overruled by the Fifth Circuit, which held that only the Supreme Court could overturn its own ruling in Rostker. Only last year, the Supreme Court declined to review the ruling, although three justices wrote that the draft likely was now unconstitutional.