Fetishizing language

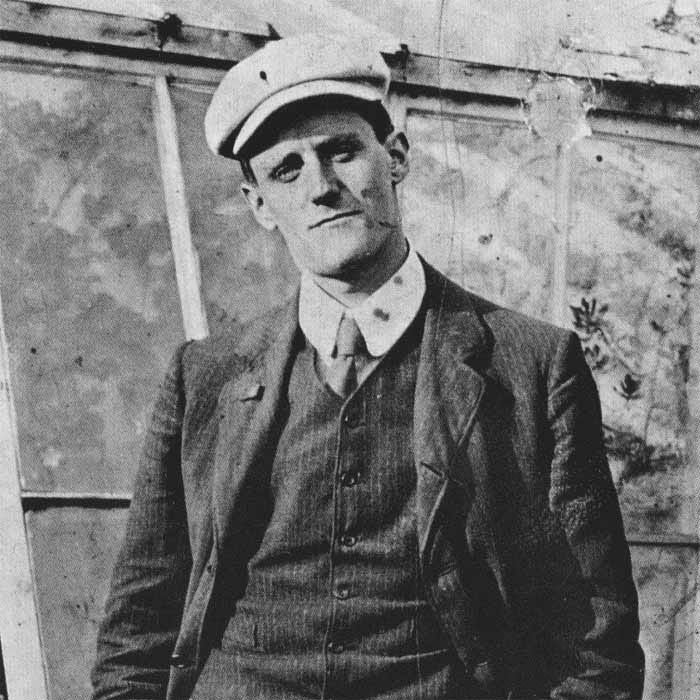

A friend reminds me that this month marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Ulysses is one of the most amazing books in the English language, loosely speaking. To anyone thinking about reading it, my advice would be to at least initially ignore Joyce’s (in)famous mania for allusions, Homeric and otherwise, and just read the thing.

Personally I find the allusive side of Ulysses makes for a sometimes amusing game, but it remains basically superfluous to the qualities that make it such a great book.

Those are the combination of Joyce’s almost unmatched stylistic genius with his deeply empathic capacity for what Keats called “negative capability” — the ability to put oneself imaginatively into the hearts and minds of a remarkable diversity of people, quite unlike himself.

And not just people: one of the many intensely memorable things in the book is a scene in which Joyce enters the mind of the dog Garryowen, and imagines what dog poetry would sound like. Typically, this scene is based on a fictionalization of an actual champion Irish setter named Garryowen owned by an actual person, a law agent named James J. Giltrap, who also makes a brief appearance. The book has endless rabbit holes like this, for anyone inclined to go down them.

Ulysses was subjected to decades of ferocious censorship, and came into print originally only because Sylvia Beach, a young American expatriate running a bookstore in Paris, who at the time knew almost nothing about the publishing business, took considerable legal and financial risks to bring the first edition of the book out on February 2, 1922, Joyce’s 40th birthday.

Today I suppose the phrase “unprintable words” is so anachronistic that it would have to be explained to the vast majority of readers not bordering on if not already actually inhabiting the uncanny valley of the aged, but originally Ulysses had a number of literally unprintable words, although the language is by contemporary standards fairly tame.

Which brings me to this CNN essay:

The podcaster Joe Rogan did not join a mob that forced lawmakers to flee for their lives. He never carried a Confederate flag inside the US Capitol rotunda. No one died trying to stop him from using the n-word.

But what Rogan and those that defend him have done since video clips of him using the n-word surfaced on social media is arguably just as dangerous as what a mob did when they stormed the US Capitol on January 6 last year.

Rogan breached a civic norm that has held America together since World War II. It’s an unspoken agreement that we would never return to the kind of country we used to be.

That agreement revolved around this simple rule:A White person would never be able to publicly use the n-word again and not pay a price.

Rogan has so far paid no steep professional price for using a racial slur that’s been called the “nuclear bomb of racial epithets.” It may even boost his career. That’s what some say happened to another White entertainer who was recently caught using the word.

It is a sign of how desensitized we have become to the rising levels of violence — rhetorical and physical — in our country that Rogan’s slurs were largely treated as the latest racial outrage of the week.

But once we allow a White public figure to repeatedly use the foulest racial epithet in the English language without experiencing any form of punishment, we become a different country.

We accept the mainstreaming of a form of political violence that’s as dangerous as the January 6 attack.

Now I fully agree that every white person should make it a strict rule to never use The Forbidden Word, and I have no quarrel with the idea that Rogan should pay a serious price for flouting this rule on numerous occasions on his $100 million Spotify podcast.

Nevertheless, the kind of fetishizing of language — imbuing TFW with practically magical powers — on display in the quoted CNN piece is in some ways problematic. A ways down that same slope lies the banned Ulysses; but on the other hand there’s something to be said for having certain loose and informal, as opposed to rigid and legal, restrictions on what sort of language is considered acceptable in various contexts.

Take a couple of scenes from the 1967 film Cool Hand Luke, when censorship was loosening up to the point where a big budget Hollywood film could use the word “bitch,” and even the phrase “son of a bitch,” at a time when the latter in particular still had a real shock value for audiences.

BOSS KEAN'S VOICE Awright, let's eat them beans. Luke stumbles gratefully toward the chowline. ON THE CHOWLINE Dogboy dishing it out to Luke. Dogboy is gleeful, gloating. DOGBOY I knew they'd git you. With them chains an a bonus of a coupla years, you runnin' days is over forever. Ah'd like to see you try to run agin. You gettin' so you smell so bad, I could track you myself. LUKE For a natural born son of a bitch like you, that oughta be easy.

I can’t find that scene on YouTube, but this one between Luke and his mother is even better. It starts with Luke’s mother saying that sometimes she wishes people were like dogs:

Here’s the scene immediately after Luke learns his mother has died:

Goddamn that is some acting.

To continue these vaguely related ramblings, I note that in Alice Goffman’s confabulated pseudo-ethnography On the Run TFW is written out of dozens of times, but always with the last two letters converted to an “a,” thus allowing an upper class white woman to walk right up to the ultimate contemporary verbal line but not cross it.

Anyway, the moral of this story is that certain limited varieties of self-censorship do have a certain amount of cultural value, although that “censorship” should be cultural rather than legal, and we should be careful not to imbue language with the atavistic power it has so often been granted.