Illiberal “Soft Power”

It wasn’t that long ago – maybe five or six years – that I last heard someone claim that Russia would never posses real soft power.

After all, who could look at Russia’s everyday corruption, its kleptocratic government, its extremely unequal distribution of wealth, and its “resource curse” economy and conclude “I want some of that!” China, with its rapid economic growth and conspicuous material abundance? Sure. But not Russia. Definitely not Russia.

It turns out (spoiler) that there are plenty of westerners who don’t care very much about democracy and the rule of law. They see Russia, and especially Putin, as a standard-bearer for “traditional values” – a bulwark against degenerate liberal values.

Russia’s soft power strategy was first deployed in earnest during Putin’s 2012 reelection campaign, but was most clearly articulated in his 2013 presidential address. During the speech, Putin announced Russia would defend “traditional values,” defined in broadly ethnic-nationalist and heteronormative terms. The speech decried “eroding ethnic traditions” and Putin vowed to protect “the values of traditional families” against “so-called tolerance.” […]

Going beyond speeches, Putin has enacted policies befitting these values, such as the 2013 Russian law banning “gay propaganda”—a move that widely appealed to religious conservatives. It is unlikely this wedge strategy is the product of feelings genuinely or deeply held by Putin, given that he has opportunistically cultivated and supported figures on the left as well.

Russia’s statements and actions attract people who share similar values, as evidenced by their reception in the West. In response to Putin’s 2013 presidential address, the conservative former politician Pat Buchanan wrote, “In the culture war for mankind’s future, is (Putin) one of us?” Likewise, after meeting with Putin in 2015, religious leader Franklin Graham said, “I very much appreciate that President Putin is protecting Russian young people against homosexual propaganda.” This cultivation also explains why alt-right marchers chanted “Russia is our friend” at their notorious 2017 rally in Charlottesville.

Of course, cultural conservatives “in the know” prefer Hungary, where EU membership helps make for a higher per capita income and, for those not at the top of the food chain, a better overall quality of life. But why choose between them when you can have both?

The synergy between U.S. reactionary populists (i.e., the dominant faction of the Republican party) and the Kremlin shows up in some very strange contexts. In the 2000s, a Republican White House supported “Color Revolutions.” In 2020, influential conservatives were describing “Color Revolutions” in ways that you’d expect to find on Russian state media.

In a recent essay, “The Coming Coup?,” the former Trump-administration official Michael Anton warns his readers that Democrats are laying the groundwork for the “unlawful and illegitimate removal of President Trump from office.” Their tactic, he says, is to condition the public into thinking that Trump will try to steal the election so that if he wins, they can cry foul. They will then, Anton predicts, organize “a ‘color revolution,’ the exact same playbook the American deep state runs in other countries whose leadership they don’t like and is currently running in Belarus.

The Kremlin certainly has good reason to believe that the “traditional values” strategy is working pretty well. It’s no surprise to see that Putin is again positioning himself on the reactionary side of the U.S. culture wars.

Some Westerners believe “the aggressive deletion of whole pages of their own history, reverse discrimination against the majority in the interests of minorities … constitute movement toward public renewal,” Putin said. “It’s their right, but we are asking them to steer clear of our home. We have a different viewpoint.”

Putin, who told the Financial Times of London newspaper in 2019 that liberalism had become “obsolete,” has loudly advocated for what he considers to be traditional family values. In his Thursday remarks, he said the notion that children are “taught that a boy can become a girl and vice versa” is monstrous and “on the verge of a crime against humanity.”

He also suggested that transgender rights supporters were demanding an end to “basic things such as mother, father, family or gender differences.”

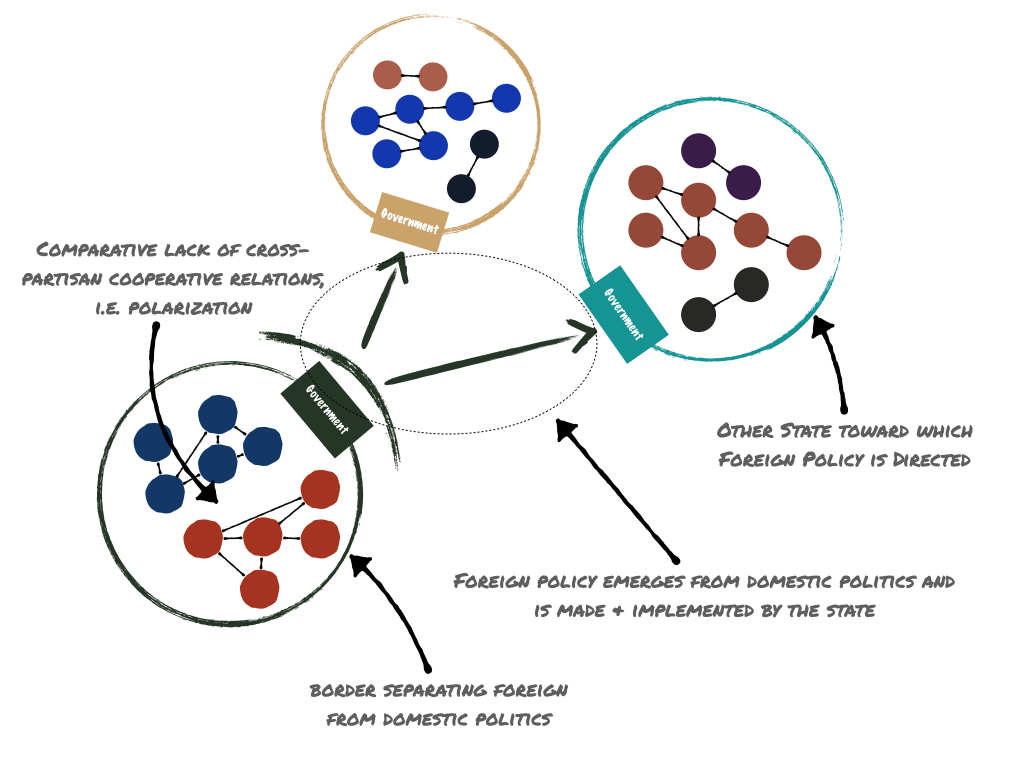

The model of international politics that dominates discussions of U.S. foreign policy and grand strategy (more on this, perhaps, later) looks something like this:

Even in a highly polarized political environment, domestic politics in great powers goes on “within the state.” How domestic political disputes play out obviously shapes foreign policy; different political factions understand the “national interest” in different ways. But the approach generally conceives of foreign policy as relatively autonomous.

Why? International constraints typically limit the range of possible foreign policies. U.S. foreign policy will always be shaped by any number of factors, such as the cost and time involved in relocating armies from U.S. territory to Europe or Asia, its natural resource endowment, and its relative economic and military power.

This, in turn, helps explain why the model treats foreign affairs as a separate sphere than domestic politics. It’s why many Foreign Affairs articles about grand strategy barely acknowledge that U.S. domestic politics are an unmitigated sh*tshow – and when they do it’s usually to lament the loss of a “bipartisan consensus” on foreign policy.

The standard model is badly broken. The one below is much closer to reality – or at least how things were shaping up by 2019.

As I’ve suggested before, it’s just plain weird to discuss many aspects of U.S. foreign policy without any attention to:

- The fact that U.S. domestic cleavages increasingly map onto political fights in other democracies; and

- How other governments – especially authoritarian ones – are responding that development.

It’s hard to take seriously recommendations for big reforms in international order that pretend the Senate is capable of ratifying new treaties – or that the US isn’t one election away from discarding a bundle of new international agreements.

I am befuddled by proposals which assume a broad consensus in favor of policies that stabilize or promote democracy. I can’t make sense of arguments in which the biggest threat to the United Sates is an unfavorable shift in the balance of power in East Asia.

It’s not like the situation the US faces is completely novel. We’ve seen variations on these dynamics before. Past instances of transnational polarization have pivoted on, variously, religion, the rights of monarchs, left-wing radicalism, and the three-way conflict among communism, fascism, and liberal democracy.

They seldom end well.