This Day in Labor History: July 2, 1888

On July 2, 1888, the London matchgirl strike began.

In the pantheon of dangerous work, we probably don’t often think of making matches. To some extent, this is because the match market has collapsed in recent decades, at least in the U.S., with the decline of smoking cigarettes and the rise of lighters. But also, it’s just a match, right? Well, no. See, the match requires a special substance to light. And in the late 19th century, that was white phosphorous, mixed with other materials. Now, one did not want to spend a lot of time around white phosphorous. It is very bad for you. The result of working with too much of this stuff was phossy jaw. Basically, the phosphorous dissolved your jawbones. While not always fatal, it also frequently caused brain damage and seizures. But this was the late nineteenth century. Society saw workers as expendable. In the U.S. and in Britain, it was considered far more important to follow supposedly natural and iron laws of profit than care about whether workers got poisoned. It’s not as if the companies were unaware that working with phosphorus destroyed workers’ jobs. They knew it quite well. So when a worker had a toothache, they had a choice: get it pulled immediately or be fired. Supposedly, taking out the tooth was going to protect the worker.

And workers did get poisoned, on both sides of the pond. Working conditions in the match factories were terrible. By the late nineteenth century, there were 25 match factories in Britain. White phosphorous was not strictly necessary for them. Two of the factories used different substances. But the other 23 did use the poison. The workforce was divided between adults and children, with women more often than men working with the phosphorus. A lot of the workers were Irish, working the least desirable jobs. There were all sorts of fines that took money away from the already meager pay–having dirty feet for instance meant you lost money, even though the job didn’t pay well enough for most workers to buy shoes. A dirty workbench, decided strictly by the foreman of course, was another reason for fines. Being late, dropping a box of matches, really anything could be fined. Naturally, it was in the company’s interest to take back as much of the wages as possible. Based in London’s East End, the workers labored fourteen hours days that started at 6:30 in the morning. They had to stand all day. They got two breaks during the day. Any additional break, say to use the toilet? Another fine! There were several strikes in the early 1880s over the low wages and the fines. They won none of them. But each built up experience, class consciousness, and a strategic reserve.

The 1888 strike began at the large Bryant & May factory, which employed about 5,000 workers and made tens of millions of boxes of matches a year. Despite its Quaker beginnings, these employers were brutal and very invested in stealing wages through fines. Meanwhile, the company paid its investors dividends of 20 percent per year. The best way to make profit was kill workers. There were always more Irish girls to hire after all. The terrible working conditions had led British reformers, specifically Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows, to publish news articles exposing them to the public. Bryant & May tried to get the workers to publish a letter denying the conditions. They refused and went on strike after one worker was fired for refusing.

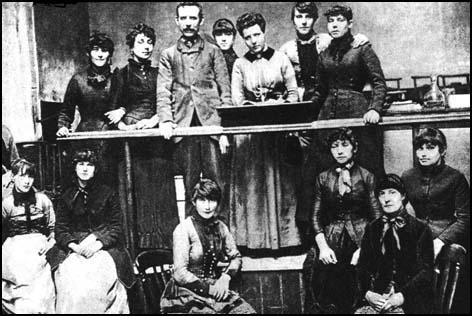

By the end of the day, about 1,400 workers, mostly women, were on strike. The matchgirls strike soon became one of the defining labor actions of late 19th century Britain. Management offered to hire the fired worker back if they would end the strike. But they refused. This is where years of anger and previous labor actions kicked in. Their lives were terrible and they wanted them to be better. They went back to their long lists of grievances and demanded a bunch of other things, especially the end of the fines. Safety itself was probably lower down their actual priority list, as these things tended to bother reformers more than the workers at this time who often accepted dangerous labor as their lot in life and struggled to see an alternative to it.

By July 6, the entire factory was on strike. A committee of 100 workers went to Besant to ask for her help in winning the strike, which she was happy to give them. At this point, she actually didn’t even know they were on strike. Soon, this got the attention of Parliament, with Charles Bradlaugh, the well-known atheist and reformer, leading support for the workers in the government. This started to crack the Quaker ownership, who identified with the Liberals. Being criticized nationally was a step too far for the owners. The London Trades Council began to get involved in support actions.

On July 16, Besant worked out a deal between the factory and the workers. The fines were gone. That was a huge win for the workers. An early system of grievance management was set up where workers could take their complaints to management instead of having to go through their hostile foreman. They also won one big safety concession–a separate room where they could eat so their food would not be contaminated with white phosphorous. What made this so significant is that big industrial concerns simply had not lost strikes in Britain before. They were used to complete victory and total control over the workers in the factories. For the first time, there was real public support for factory workers. This concerned the British elite greatly, though they remained largely union free in the factories for some time to come. This victory also laid the groundwork for industrial unionism in Britain. Prior to this, most unionism was in the skilled trades, as it was in the United States. But now, with this victory under the belt of the working class, there began a greater emphasis on large-scale organizing in trade unions that would organize the unskilled masses. Even if they were Irish.

In the next several years, conditions did get safer because the match industry started moving to red phosphorous, which was less toxic. But that was more expensive and several factories continued to use white phosphorus. It was only in 1908 that the government passed a law phasing out the substance, which went into effect in 1910.

This is the 400th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.