Pittsburgh: America’s South Africa

I like Pittsburgh an awful lot. It’s one of my favorite cities in the east. But there’s no question it is has massive racial problems. Jerry Dickinson is a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh. He throws down the gauntlet by comparing his experiences in Pittsburgh to South Africa.

Over a decade ago, I was walking along a muddy and crowded alleyway between hundreds of shanty houses in Alexandra. Alex, as it is known, is one of post-apartheid Johannesburg’s most segregated slums and bastion of inequality. I was a young human rights activist and Fulbright Scholar living in South Africa and had just finished advising a group of residents over a water rights dispute. I exited the alleyway onto a busy street. As I weaved through a traffic jam of minivan taxis, known as kombis, a group of giggling young Black children pulled me aside and playfully threw a tennis ball at me. They knew I was not a local and were curious to interact. I smiled and crouched down. I caught a few passes, gave some hugs and continued on my way.

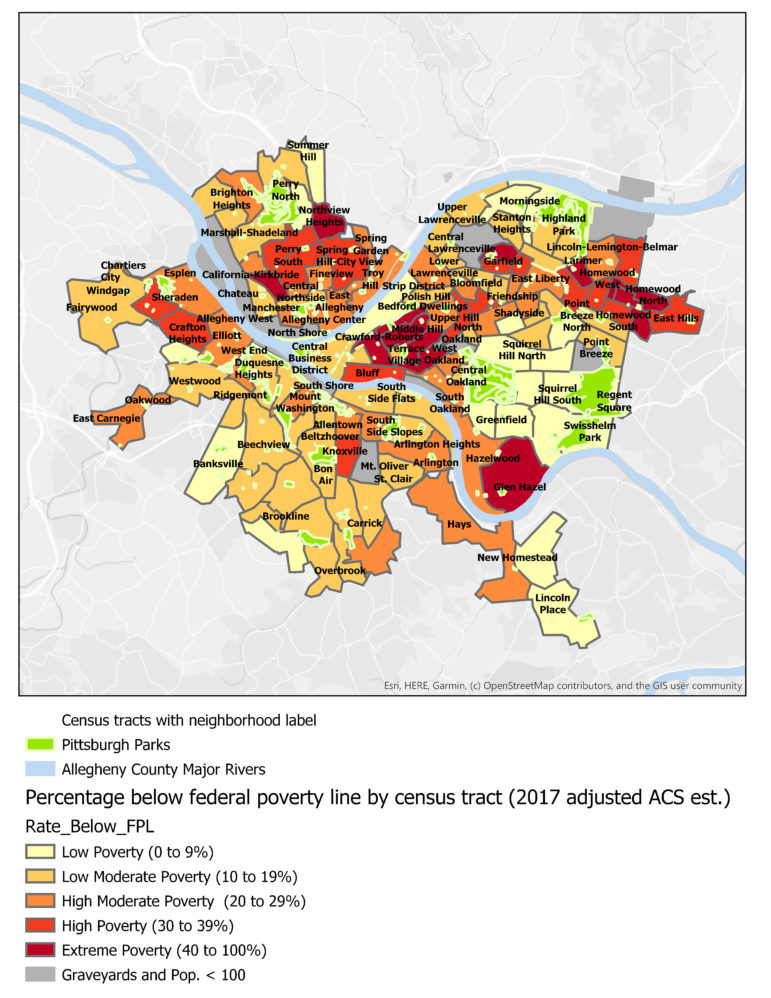

A decade later, I was criss-crossing the Pittsburgh region to knock doors and meet residents as a candidate for U.S. Congress, before the pandemic abruptly sidelined my travels. I met a Black single mother of three young children on her porch in a dilapidated home in the city’s segregated Hill District. We spoke of housing issues. I could hear her kids playing and giggling inside. They peeked out the window to see whom their mother was speaking with. I smiled at the kids. But, I turned solemn as I departed that pleasant exchange. Like the children in Alex, Black children in my hometown were growing up in one of the nation’s least livable and unequal cities for Black Americans, according to the landmark race and gender equity study published in 2019. At that moment, I had arrived at an uncomfortable truth. Pittsburgh was America’s apartheid city, not the nation’s most livable city.

It is a jarring comparison at first blush. The legacy of South Africa’s apartheid had forcibly, by law, separated people by racial classifications and into geographically isolated districts. The result was severe levels of occupational segregation. Schools were separated along race lines and the gap in education achievement was wide. Health outcomes for women and children were markedly different between whites and Blacks. The economic chasm across race was growing. It was indisputable that the apartheid legacy contributed to Johannesburg’s vast levels of racial inequality. How could Pittsburgh possibly compare? At best the contrast seemed historically inaccurate and at worst culturally and racially insensitive. But, as sociologists Nancy Denton and Douglas Massey once explained in their seminal work, American Apartheid, “Americans have been quick to criticize the apartheid system of South Africa, [but] they have been reluctant to acknowledge the consequences of their own institutionalized system of racial separation.”

Yeah, that’s the truth. Lots of people are comfortable talking about racism as something that other people do. But ask them to confront their own privilege and, well……

Dickinson goes on to provide a lot of detail about Pittsburgh’s problems. He then lays it out in a way that applies to everywhere in the U.S.

The city has one of the highest rates of occupational segregation between whites and Blacks in America. White women make 78 cents to every dollar, while Black women make just 54 cents. Black men have some of the lowest average incomes in the country. The sharp division in employment and occupational inequality between whites and Blacks also leads to significant differences in educational attainment across race. White men and women are three times more likely to have a college degree than Black men and women. Black men are two and a half times more likely to drop out of high school than white students. This is modern American apartheid.

A moral reckoning is upon us. We must reorient the lens for which we gaze at Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh is not the nation’s most livable city. It is America’s apartheid city. The future success of any metropolis depends on a moral vision that its residents feel they can identify with and attach themselves to. It is obvious, then, that our collective moral imperative is to end Pittsburgh’s apartheid and to become a world-class city of racial equality. That is our vision for Pittsburgh. That is our moral imperative. As a father of two Black daughters, whether we choose to pursue this vision and embrace this imperative will be the defining characteristic of our generation.

Until these disparities are equalized, America’s legacy of racism will not only not be erased, it won’t even be diminished. But god forbid we talk about the racist consequences of science and technology or ask our children to go to schools that those people attend. And don’t even get me started about my property values.