The Nino Who Said "NI!"

The rule of law? Vaffanculo!

Between Scalia’s recent civility and judicial conduct issues and attending this excellent (if depressing) conference last Friday I was reminded of my favorite assessment of Bush v. Gore, Kim Lane Scheppele’s “When the Law Doesn’t Count: The Rule of Law and Election 2000.” It does a marvelous job of analyzing all of the legal issues, as well as adding interesting comparative perspectives. It’s all worth reading if you’re into this sort of thing, but a couple of points are worth extra emphasis. One of the countless ways in which the decision was utterly lawless that I haven’t mentioned was the obvious Catch-22 the Supreme Court presented the Florida courts with. The Court ruled that the recount ordered by the FSC violated equal protection because the recount didn’t have a uniform standard; and, of course, the recount didn’t have a uniform standard because the Supreme Court told the Florida courts not to use one. As Scheppele points out, to be engaged in this kind of gamesmanship is not be meaningfully engaged in “law” at all:

The U.S. Supreme Court majority in the story of the 2000 election seems to have taken its inspiration from the Knights Who Say NI! in the Monty Python version of the Arthurian legend. Dressed in dark uniforms and towering above the petitioners who came before them, the Justices of the Supreme Court possessed the magic words that, when shouted in chorus, caused those who needed their permission to proceed to cower before them. For it was by pronouncing the magic words that the Supreme Court Justices could cause the most self-confident pretender to the throne to slink away. And, as in the standard fairytale, the Court could set a challenge for the pretender to the throne who, if he met the challenge, must be allowed to get what he sought. The majority’s reading of the fairytale requirements, however, follows Pythonesque conventions rather than the standard ones, and it deviates substantially from what the emerging comparative constitutional standard for rule of law would require.

Between Bush v. Palm Beach County Canvassing Board (the protest phase case) and Bush v. Gore (the contest phase case), the Supreme Court turned itself from the Knights Who Say NI! into the Knights Who Go Neeeow … wum … ping!, no longer “contractually bound” to be satisfied by a litigant who met the challenges that were set originally and who was therefore looking to pass. Transforming itself into the Knights Who Go Neeeow … wum … ping!, the Supreme Court had other ideas. In its new guise, instead of being satisfied by a shrubbery brought before it designed according to their initial request (a solution crafted under a literal reading of the Florida statute), the majority insisted on a new shrubbery with a totally different design (federal constitutional equal protection analysis rather than the literal wording of the Florida statute set the standard). New magic words were necessary to pass through this part of the dark forest of the law, except that the Knights had obviously tired of the game and so simply declared it over.

What is wrong with this, on a rule-of-law account? A great deal, but let me concentrate on two things in particular:

(1)The Whipsawing Problem: There was an apparent shift in the legal frameworks that were found to be important as one case followed another, leading to a sense that the applicable law was not stable and making it very difficult for anyone to orient their conduct in light of the law either before, during, or after the sequence of litigation.

(2)The Impossibility Problem: There was, in the per curiam opinion in Bush v. Gore, an announcement of two crucial legal conclusions – that an equal protection test applied to court-ordered vote-counting procedures and that 3 U.S.C. 5 combined with a “legislative wish” required that recounts not be extended past the December 12 “safe harbor” date. But these two conclusions worked at cross-purposes. Meeting one required violating the other, and vice versa. With this logic, there was simply no place left to stand to claim a remedy that the law seemed to allow and perhaps even to require. The election was declared over as it stood at the moment the Court issued its decision, and no state has ascertained whether the results as they stood on the evening of December 12, 2000 met the equal protection standards the court laid down.

From all of this, we might legitimately wonder whether the United States in fact decided its most recent presidential election according to any coherent law at all.

Between the moving goalposts and the fact that the remedy was completely indefensible given the purported constitutional violation, Bush v. Gore was wholly unprincipled even leaving aside the lack of precedent for the legal argument and the glaring contradictions with the past jurisprudence of at least three members of the majority.

Scheppele also demolishes the claim recently made by Scalia that the Court had no choice but to rule because it was dragged into the case by a politicized Florida court. This implies that the court violated the clear language of the Florida election statute to produce a desired outcome. But Scheppele points out numerous “infelicities” in the Florida election statutes, pointing out the vague language and internal contradictions that make the readings of both the majority and dissenting opinions of the FSC perfectly plausible. Particularly important are infelicity #4 (“In the “contest” phase under Florida election law, a candidate who still believes that there are serious flaws in the election tallies may challenge the certification of the election results. Unlike in the protest phase when the complaint goes to the county canvassing boards for their resolution, the contest phase sends all complaints directly to the Florida courts, which are given very broad latitude to investigate and fashion remedies to fix any complaints they find to be valid. But this great judicial power does not come with many critical constraints – the most crucial one in the presidential electors context being whether there are any deadlines in the process”) and #5 (“If a judge decides that a contest identifies a legitimate problem, then under section 102.168(8) of the Florida Statutes Annotated, the judge can “provide any relief appropriate under such circumstances.” There is no further guidance to the judge.”) The idea, then, that the FSC “usurped” the power of the Florida legislature is absurd: the legislature, in fact, delegated broad powers in resolving election disputes to the courts. And, as I mentioned yesterday, the FSC used a contestable but plausible reading, and it adhered to this reading consistently whether it helped Gore or Bush.

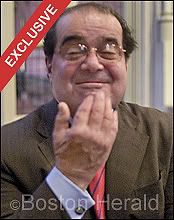

So the claim made by Rehnquist, Scalia and Thomas that the Florida Supreme Court wasn’t engaged in jurisprudence at all couldn’t be more implausible–but it certainly is a reasonable description of their own work. A mild obscene gesture would be a polite way of responding to Scalia’s next pompous lecture about the alleged failures of other judges.