The New Fugitive Slave Act

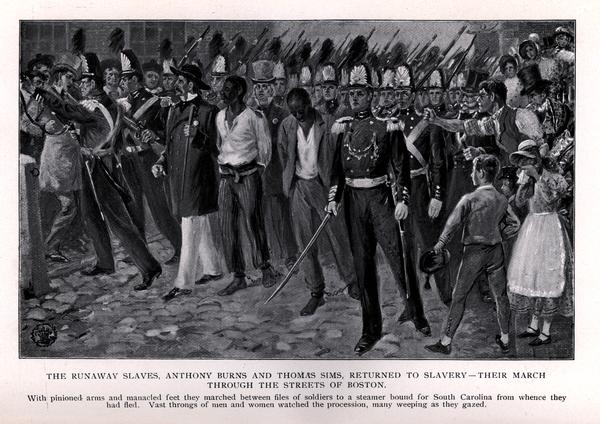

See, before the Fugitive Slave Act, most Americans, even what would pass for “liberals” of the time (if we are trying to shoehorn people into modern categories, which isn’t very useful) didn’t really care all that much about slavery. It was far away and they mostly didn’t like Black people anyway, very much including the whites of Boston. But the South couldn’t help itself from overreaching. The very small number of slaves escaping to the North did not have that great of an economic impact on the South, though of course it might on the individual owner. But the idea was so outrageous to the South that it militarized the nation to get slaves back. Actually seeing people rounded up and thrown into prison and returned to slavery, now that angered the North. People didn’t care if they didn’t have to see it, but if they did? That’s a whole different story. So after the kidnapping of Anthony Burns and the near violent revolt that accompanied it, the Fugitive Slave Act was effectively unenforceable in Boston.

See any connections between that and the current response among northern liberals to our long racist, violent, and murderous immigration enforcement system?

Cobb:

Attempted enforcement of the law met with immediate resistance. In 1851, an armed mob surrounded a group of agents led by a slaveholder, Edward Gorsuch, in Christiana, Pennsylvania, who were attempting to return four fugitives to his farm, in Maryland; Gorsuch was shot and killed. The four, along with others who participated in the standoff, escaped, and some reached Canada with the assistance of Frederick Douglass. In Syracuse, New York, Oberlin, Ohio, and other cities, crowds swarmed jails where captured fugitives were held in other successful efforts to free them, at the risk of their own prosecution. (In 1854, fifty thousand people filled the streets of Boston, a center of abolitionist resistance, to protest against returning Anthony Burns, a Black man who had escaped from slavery in Virginia, to that state. (When that effort failed, a group privately purchased Burns’s freedom and facilitated his return to Massachusetts.)

The significance of this history is twofold. The Fugitive Slave Act was rhetorically useful for a certain element of the political class, but for most people it took an issue that they may have felt ambivalent about—or hadn’t much thought about at all—and gave them a direct, visceral reason to feel very strongly about it. Slavery might have been an abstract national concern, but the fate of a neighbor, whom people may have depended upon as a part of their community, was very much a personal one. Something akin to that reaction is occurring in communities across the U.S. now, as social-media feeds fill with images of children being harassed by ICE agents as they leave school and of a five-year-old boy being detained, and of adults being shoved to the ground and pepper-sprayed or pulled from their cars after agents smash the windows. The Fugitive Slave Act is remembered by historians for its ironic effect: designed as a means of cooling the simmering regional tensions over slavery, the law effectively made it the most contentious issue facing the nation. It pushed Americans toward the realization that the nation was bound in what William Seward later termed an “irrepressible conflict.”

In Minnesota, the distance between the past and the present is small. Americans hold complex views on immigration and deportation, but as early as last summer more than sixty per cent of Americans opposed undocumented immigrants being sent to the CECOT facility in El Salvador, where they were likely to suffer abuse. (It’s significant that the Administration’s campaign in Minneapolis began amid renewed discussions of the reported torture that detainees experienced after being deported there.) In this regard, many Americans are asking themselves the same question that an earlier generation asked a hundred and seventy-six years ago. Judging by the bundled, frostbitten crowds that return to the streets day after day despite the violence directed at them, they have come to the same answer.

As I say, there’s a lot of overlap here. When I teach my Civil War course, one of the things I really emphasize to my students is that the South consistently overreached and overreacted and if they hadn’t, slavery would have lasted for a long time, since in 1861, it was incredibly profitable and the number of white Americans who really wanted abolition was small. That number was much, much smaller before the Polk administration stole half of Mexico to expand slavery, before the Fugitive Slave Act, before the Kansas-Nebraska Act, before the bloodshed in Kansas and the bullshit Lecompton Constitution to sneak that territory in as a slave state against the will of the whites who actually lived there, before the execution of John Brown, before secession. The South couldn’t stop overreacting and taking people who were effectively indifferent to slavery and turning them into people determined to fight the Slave Power at all costs.

Given that the Trump administration’s heroes include the lead figures of the Slave Power, it’s unsurprising that they would follow the same path of massive overreaction that politicizes huge swaths of once indifferent people who don’t want to see fascists kidnap people on the street and kill those who don’t like that.