This Day in Labor History: December 10, 1906

On December 10, 1906, workers at the General Electric plant in Schenectady, New York, conducted a sit-down strike. This is the first known sit-down strike in American history. We don’t know very much about it in fact. There’s little scholarly information on it and while online Marxists have tried to play it up as something pretty big, it was really more of a one-off attempt by rank and file workers to save the jobs of a few coworkers at a particular time. That said, even when you don’t know too much about a moment in our labor history, it’s still worth shining a light on to see what we can find out and figure out if there are any lessons for us in the present.

The Industrial Workers of the World were founded in 1905, though it wasn’t much of an organization at that time. It had goals vaguely around syndicalism ,but in its early years attracted leftists of various stripes. It’s hard to say it had a coherent ideology, but it did believe generally in two things. First was organizing the unorganized. Second was direct action on the shop floor. Both of these principles put it in direct conflict with the American Federation of Labor, which hated leftists of all stripes, did not believe in industrial organizing and also did not believe that others should engage in industrial organizing. Thus, any time that the IWW would enter a workplace, even though the AFL had no intention of organizing those workers either, it would work directly with employers to stop the IWW. It was not a good situation in American labor organizing.

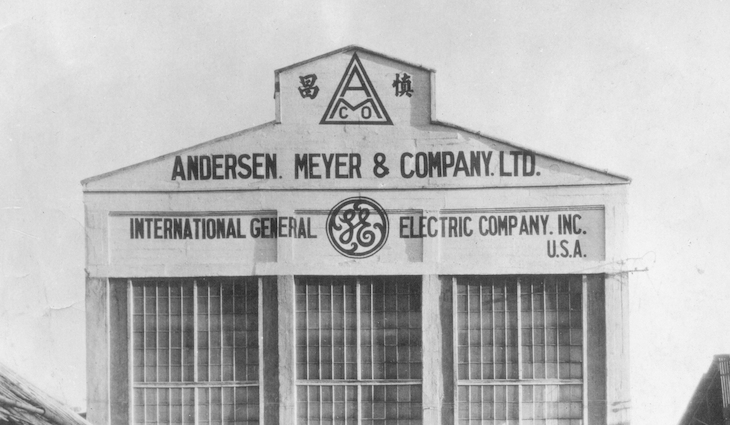

One of the first places where workers showed interest in the new IWW principles was the General Electric plant in Schenectady, New York, its big central hub. I’m not sure that management even really knew what was going on when, in December 1906, it fired three workers from the switchboard draughting department. Now, this was not an IWW-organized facility. The IWW wasn’t really capable of that and also the IWW didn’t really engage in this kind of organizing. It was more that there were some workers on the shopfloor who had become familiar with the IWW, liked what they had read, declared their allegiance to the organization’s ideas, and talked to their fellow workers about them. That’s basically what those articulating those IWW ideas wanted anyway.

There were probably between 2,000 and 3,000 workers at this GE plant. There’s not really any evidence that when strikers sat down on the job, it was some deeply thought through strategy. The idea of the sit-down as a thing wasn’t really articulated until later and which became famous only with the Flint strike in 1937. They just didn’t want their jobs taken by scabs and they decided at the moment that this was the best strategy to prevent it. But that’s what they did. It was shortly after this that the IWW moved its limited resources toward promoting the strike, though don’t overstate this–a few people showed up to help organize and that was about it. The IWW just had no capability to do more at this point and honestly it rarely would. It never had any real money. It was people power and publicity that it could offer.

The strike itself was a flash affair, with a demand of getting three fired workers rehired. GE simply refused to consider their demands. Some workers stayed in, others went out. The AFL had zero interest in showing solidarity. In fact, it didn’t even understand what solidarity was, which was the creation of mutual aid networks to help workers help each other. It simply saw this as some socialistic threat come to American shores and, worse, the American workplace. There were a few AFL workers in there and it’s likely that their unions ordered those workers to do nothing to help anyone associated with the IWW, however those workers might have felt about it, and of course we have no idea the answer to that question. The IWW claimed they were winning the strike and that shutting it all down would lead to a win. The company claimed it was bringing in all sorts of scabs and had the situation under control.

Historical information on this strike’s details remain sketchy. They are historians who have studied labor at GE, but mostly focusing on the 30s and after. So we really don’t know that much here. But, again, it’s worth a discussion of what we do know. After all, most labor actions are effectively forgotten about anyway. There’s a few details though. The Wellsville Daily Reporter, a local newspaper, reported on December 15:

“Assurances of support from the Western Federation of Miners were received from Denver and served to encourage the 2,000 or more striking members of the Industrial Workers of the World who left their places in the plant of the General Electric Company on Tuesday last. The strike leaders say that the miners have an organization of about 40,000 men who can be depended upon to give them financial aid. Messages of a similar character have been received by the strikers from branches of the Workers in New York, Chicago, and Paterson, N.J.”

The strike fell apart a few days later though. A deal was struck on December 19 that basically said that the three fired men were not going to be rehired but the other strikers would be. Incidentally. it seems that the legendary Irish organizer James Connolly was involved here. We don’t know much, like we don’t know much about any of this. But at the time, Connolly was working in Troy, which is a few miles away. He was involved in several regional strikes, giving speeches for the Socialist Labor Party. So he was probably involved here too. We probably won’t ever know for sure.

This is the 584th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.