July Reading List

Here’s my list of books read in July. Last month’s list is here. You can follow previous months from there. This goes out to my book patron, known as PS, who sends me books that make up a good portion of the fiction list. Your generosity is beyond appreciated. This is also your monthly thread on books so talk about what you’ve read, which I hope to god includes some fiction. What is the saddest sentence in the English language? “I don’t read fiction.”

Professional Reading:

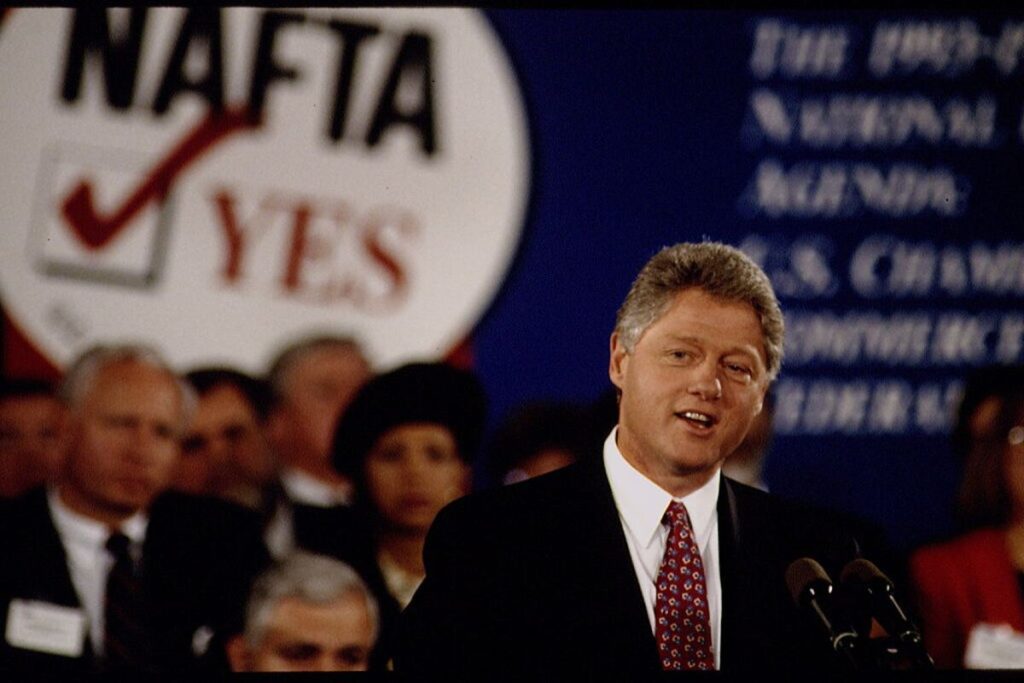

- Gary Gerstle, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era (Oxford University Press, 2022). Gerstle co-edited The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order back in 1989. That was an important book. Three decades later, watching the rise and fall of the neoliberal order, he decided to write a history of that period. It’s hard to do. First, are we through with the neoliberal order? I’ve heard other well respected historians argue this too and I tend to agree, not because deregulation is over but because the nation has now entered a period of just open corruption. Plus at the center of neoliberalism was the idea of open borders, open exchange of culture, and free trade. All of that is pretty much dead with Trump. Feel free to disagree of course but Trump hates everything about neoliberalism. Anyway, Gerstle does a good job on the rise of the neoliberal order, but the fall tends to be a pretty standard history of Obama/Trump/Biden, up to the early moments of the Biden administration. But it’s awfully hard to do anything more than chronicle what is going on as it is going on. It’s still a useful book.

- Holger Droessler, Coconut Colonialism: Workers and the Globalization of Samoa (Harvard University Press, 2022). Not easy to write a labor history of Samoa for a number of reason–lack of archives, lack of Samoan voices, etc. But Droessler writes a very solid history that argues for the centrality of these small islands in the history of colonialism and globalization. He examines all sorts of workers–the copra farmers, imported Chinese laborers, educated Samoans doing translation work or accompanying German or American (the islands were split between the two, with New Zealand taking the German ones after World War I) travelers, the Samoans who ended up on trips for World’s Fair for the whites to see exotic people like they were in a zoo. Overall, it’s about as good a labor history as I think one could write on this place. Good book.

- Nora E. Jaffary, Reproduction and Its Discontents in Mexico: Childbirth and Contraception from 1750 to 1905 (University of North Carolina Press, 2016). An excellent history of reproduction and attempts to stop it in colonial and 19th century Mexico. There’s actually quite a bit of pre-1750 material in here too, often drawn from secondary sources, to explore how issues including abortion, childbirth, midwifery, contraception, and miscarriage were seen over the centuries. One thing that’s important for everyone to remember is that the idea of history as a march of progress is just not true at all. Again and again here, we see what so many histories show us–that things got much more repressive during and after the Enlightenment than they were in the early modern period. Turns out the rise of modern “science” was a superb tool for repression, in this case of women, but as many other historians have shown, of people of color around the world. In Mexico for instance, basically no one seems to have cared about abortion in the colonial period, but the Porfiriato of the late 19th century with their modern theories sure did and prosecutions of women rapidly rose. That’s just one example. In fact, Jaffary openly rejects the idea that women today are somehow more liberated or highly valued by society than three hundred years ago.

- Tristan G. Brown, Laws of the Land: Fengshui and the State in Qing Dynasty China (Princeton University Press, 2023). Going way outside my comfort zone on this one. This is a truly fascinating legal history of the Qing Dynasty through examining the role of fengshui in understanding space. With China rapidly changing, especially in the latter decades of that dynasty, fengshui played an outsized role in legal cases, such as developing mines or telegraph lines. I guess it’s as legitimate a legal construct as any other.

- Max Krochmal, Blue Texas: The Making of a Multiracial Democratic Coalition in the Civil Rights Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2016). There’s been a big upsurge over the last 15 years or so in books about cross-racial coalitions in various places. They are of varying quality, often wishcasting and reading more into them than what really existed, a constant problem for leftist historians who wish America wasn’t what it was. There are some exceptions. My former colleague Shana Bernstein has a very good book on Los Angeles. Krochmal’s book on Texas between the late 30s and the mid 60s is another. This is a really deep dive on how Black, Mexican, and white liberal communities tried to work together to transform Texas politics over that quarter-century. It didn’t always go well. And obviously Texas never became some kind of liberal place. But these campaigns still did things such as fight the poll tax and bring workers’ voices into Texas politics. The thing that makes this so good is what I would rarely praise–it’s long. Usually, when I read a 400+ page book, I see the places where editing could take place. Here? The book is exactly as long as it needs to be to allow readers to really understand the depth. Very good book.

- Mary Bosworth, Supply Chain Justice: The Logistics of British Border Control (Princeton University Press, 2024). Criminology is a very frustrating field to both myself and many other historians I know. It’s grown by leaps and bounds, largely because students watch a lot of CSI and think that majoring in Criminology is a great future of them. And lest you think I am being my usual snarky self, this is the explanation told to me by a criminologist colleague of mine for the major’s popularity. But that’s not really my issue–I don’t care what students choose as their major. My problem is that most of the field is inherently compromised by the reality that to do this research, you have to maintain good relations with the cops or prison officials or other officials of the carceral state, meaning you can’t really criticize them that much. Again, I’ve heard criminologists express this themselves as a problem, though they are less concerned about it in my experience than I would be. But hard to condemn the carceral state when you rely on the carceral state for your professional research. Pretty serious conflicts of interest. That’s what I thought of her, on this book where the criminologist Bosworth explores the working conditions and thoughts of employees working in British’s neoliberal immigration system, talking to the workers laboring for the contracted companies in charge of deportations. That’s not unimportant–though honestly the findings aren’t all that interesting, turns out that working in an outsourcing situtation isn’t super. We do need to know what these people are thinking. But as a field of its own with these sorts of compromises inherent to it, I dunno…….

- Vera Keller, The Interlopers: Early Stuart Projects and the Undisciplining of Knowledge (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023). This is an interesting book about a topic where I don’t bring a ton of background knowledge. Keller explores the “project” guys of this era, rich people sucking up to James I by proposing lunatic projects that would supposedly change the world and bring massive wealthy into the British crown. But she takes them seriously, noting that the roots of the scientific revolution were based on massive violence and exploitation that resonates to today through the colonial outposts where so much of this took place. Given the fantastical idiots trying to destroy the basic tenets of humanity through AI, this book takes on unexpected resonance today.

- Lucie Genay, Under the Cap of Invisibility: The Pantex Nuclear Weapons Plant and the Texas Panhandle (University of New Mexico Press, 2022). Genay is a French historian of the nuclear United States and this book is both a history and a sociology of the Pantex plant in Amarillo and the people who live around it and defend it based on God, Country, and Profit. There’s a bit of pushback when Pantex was potentially the choice to be the nation’s nuclear dump site, but that’s about it. There’s a few people around who protest all the horrible things going on there, but not many and they are seen as weirdos, outsiders, and communists. It’s a depressing part of the country.

- Toni Gilpin, The Long Deep Grudge: A Story of Big Capital, Radical Labor, and Class War in the American Heartland (Haymarket Books, 2020). Gilpin explores the Farm Equipment Workers, the communist union her father was involved with and its fight against International Harvester and then, when the anti-communist backlash hit after World War II, the United Auto Workers. It’s a good book, but Gilpin most definitely does the labor historian thing of romanticizing small, lefty unions that had no chance of ever leading the labor movement. Like for a lot of these books, Reuther is the anti-communist bad guy. Given that the rest of the nation–and much of the labor movement–saw Reuther as way too far to the left, it does add to the skewing of the field of labor history way far out to the left of the actual labor movement. Honestly, as a field, labor historians do not provide a very full vision of the American labor movement. Of course, one can forgive this in a study that is also a family study. Also, International Harvester was one evil company.

- Kellie Carter Jackson, We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance (Seal Press[Hachette], 2024). Jackson, one of the most prominent historians of Black activism working today, completely rejects the white liberal nonviolence fetish–which is not the same as rejecting nonviolence–and highlights the forceful way Black Americans have resisted oppression in five categories–revolution, protection, force, flight, and joy. An absolutely must read, especially for the white liberal world whose vision of King’s nonviolence isn’t much more accurate an understanding of his thought than white conservatives who cynically claim him. And please, don’t start whining about this–just buy and read the book and then we can talk. Like so much history these days, it’s a very accessible read for the average educated person. And a very good one. Easily the one history book I’d most suggest to you that I read this month.

Fiction/Literary Non-Fiction

- Don DeLillo, End Zone. How I had not read a DeLillo book on football before? I do not know. It’s certainly a solid part of DeLillo’s catalog and I enjoyed it, but honestly, it also feels like a smarter version of M*A*S*H, both the book and the film, if not the TV show. Obviously the football scene at the center of the latter two invites the comparison, but there’s definitely the same somewhat cliched, if not inaccurate, views of football culture combined with reveling in characters playing it who are also countercultural figures in one way or another. The DeLillo book is much better of course.

- Leonard Gardner, Fat City. I’ve read this once before and I am glad I read it again. Gardner chronicles marginal boxers in a marginal town–Stockton. These guys are dumb palookas who treat women poorly, are on the margins of society, drink too much, end up working as day laborers picking crops to make ends sort of meet, and come and go from the gym, where they mostly get their ass kicked. He paints their portrait wonderfully. I need to see the movie from the early 70s with Stacey Keach and Jeff Bridges.

- José Saramago, Death with Interruptions. One of my favorite Saramago novels and certainly my favorite of his later work, enough that this is probably the 3rd time I’ve read it. Death, or this version of it, is repsonsible for one country. But she–and it is indeed a she–gets bored, so she stops working for awhile. This causes immediate joy when no one dies and then a massive problem that threatens to overwhelm society. So the first half of the novel is about society dealing with this, which invites organized crime who will transport your sick loved ones over the border to die in a different country for a cost. Death decides, fine, I will get back to work but I will send everyone a letter first to give them a week to prepare. Of course no one wants those letters. Then one letter keeps getting returned. She goes and finds out who it is, which is an orchestra musician. So she transforms into a person to enter the human world. And what if Death then falls in love with this guy?

- Mary McCarthy, The Company She Keeps. I don’t know much people read McCarthy anymore (given how much time people spend commenting on the internet, I can suggest people read her instead) but they should. When they do read her, it tends to be The Group and there’s a good reason for that. It’s a great novel. But I am an even bigger fan of her earlier work, when she was eviscerating her own social scene of young privileged lefties in the 30s and 40s debating war and the New Deal while sleeping with each other. She knows it’s all bullshit and these people are poseurs, even as she is one herself. This is her first novel, a bunch of stories around Meg, i.e., herself, a divorced young woman who if fashionable and intense and who sleeps with a lot of different men and gets engaged to too many of them that she then bails on. She appears in very different ways in these stories, sometimes at the center, sometimes on the periphery. She was often criticized for being gossipy, and I suppose that’s fair enough, but it was a rich milieu for someone with very little tolerance for bullshit and a very sharp eye and ear. Then in the last story, she turns her acid on herself, in a story about her and her shrink where she examines the disaster of her life at that time. It’s just great.

- Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest. I love Red Harvest. It’s the ideal noir. Everyone is the most dreadful, awful, horrible person possible, starting with our private investigator protagonist, who gets really pissed off when the aging William Clark-based copper capitalist plays him for a sucker and he decides to clean up the whole town by getting all the crime figures to kill each other. The death toll in this little book is immense, like watching The Wild Bunch.

- Michael Tolkin, The Player. I saw the movie a million years ago, but I hadn’t read the book and then I saw it in a used bookstore. Like the movie, the book isn’t quite as good as advertised. The version I got said that this is how Hammett would write about Hollywood. Reading this right after finishing some Hammett–no. He would not. But the tale of a complete scumbag Hollywood producer who is threatened by one of the many writers he blows off and ends up killing another writer and then falling in love with his girlfriend is indeed a worthy one-off. Of course Hollywood loves nothing more than talking about itself so everyone wanted into the film version, which Tolkin also wrote. That this was really the only great idea in Tolkin’s life kind of sums up the limitations of the book, but hey, if you are only going to have one great idea, you could do a lot worse.

- Don Carpenter, Hard Rain Falling. This is a grim book and a brilliant one. Carpenter, in his debut 1966 novel, tells the story of a man who was put into an orphanage as a baby. His life is horrible. He’s a tough hood, filled with a rage he can’t even understand. He fucks up over and over again, eventually ending up in San Quentin. There, he ends up reuniting with a guy he used to know as a kid in Portland, a Black pool shark who had his own journey to screw up his life enough to get into San Quentin. They become cellmates and begin to have sex and fall in love, but the protagonist can’t admit it to himself. Then his friend/lover gets himself killed to save him from the prison rapist crew. He finally gets out, meets a woman, sort of falls in love, and there’s a sorta kinda bit of redemption, but only to a limited point. It’s a story of personal growth from grimness undiminished by taking the redemption too far into some cheesy place. It’s a deeply realistic novel. It deals with both race and homosexuality in incredibly honest ways for a white writer in 1966. And it moved me very deeply. A truly great novel. When New York Review Books republished it, they got George Pelecanos to write the introduction and it’s a great choice. It’s not exactly the kind of crime novel Pelecanos is known for, who was the second most important person in developing The Wire, among many other things. But like The Wire and much of his fiction, it’s a realistic story of people dealing with a horrible hand who have very limited choices in their life and are going to fuck up what chances they do have because they just aren’t’ equipped to survive in the world. Also, one thing that helps redeem the protagonist here is starting to read the classic authors. Imagine that, people reading instead of being on their phones or the goddamn internet. Hard to even imagine that twist in a story today.

Talk some books!