This Day in Labor History: November 4, 1942

On November 4, 1942, copper miners in Butte, Montana went on strike to protest the use of Black miners on the job. One of far too many hate strikes during the war, this strike is particularly important because the miners were organized in Mine, Mill, a leftist union explicitly dedicated to interracial unionism. But that didn’t mean that the rank and file felt that way, a frequent problem in the labor movement.

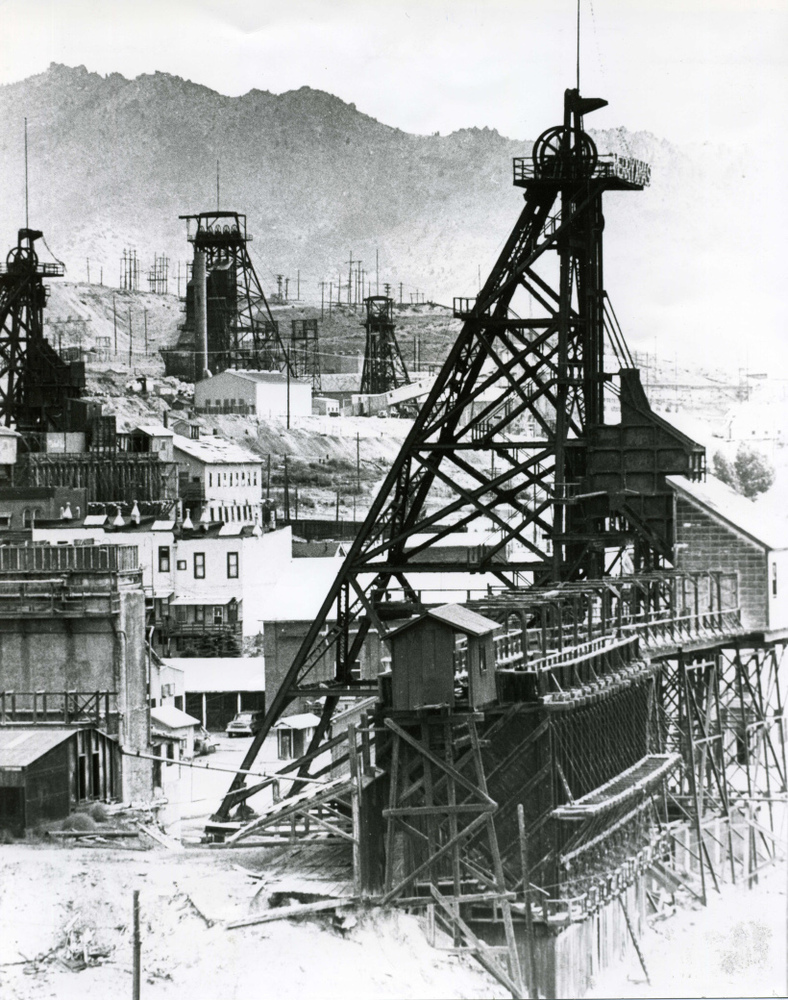

Butte had a long labor tradition, going back to the late 19th century. Once known as the Gibraltar of Unionism, by World War I, Anaconda had ground the union movement down the ground. Frank Little went there to try and organize workers into the IWW, but not only were the workers not very interested, but the mine companies lynched him. But the Butte Miners Union reformed and eventually affiliated with the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, better known as Mine-Mill. That union was the descendant of the Western Federation of Miners, founded after the Coeur d’Alene strike of 1892. It had a decade of success, mostly in Colorado, before being crushed in 1903, which led its radical leadership to help form the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905. The next generation of WFM leadership moved it away from the IWW and back toward the mountains, where it continued to survive, if not thrive. It changed its name to the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers in 1916.

By the 1930s, Mine, Mill continued to have radical leadership, dedicated to interracial unionism. But the fact of the matter was that while the mines and smelters were ethnically diverse, with all sorts of eastern and southern Europeans having joined the Irish, they generally were not racially diverse in the sense of having Black workers.

In 1942, Mine, Mill, like every other union outside of the United Mine Workers of America, had taken a no-strike pledge to win the war. This was the rare thing to unite American labor. Mainstream unions wanted to show their patriotism and leftist unions wanted to help the Soviets win. At the same time, there were labor shortages in key sectors for the obvious reason that so many men had gone to fight the war. That led to all sorts of things, from the rapid rise of women in industrial jobs to the Bracero Program to bring contracted and easily exploited Mexican workers into American agriculture. It also led to the creation of the U.S. War Manpower Commission. Part of what the WMC did was to ensure that companies follow FDR’s Executive Order 8802 desegregating industries with defense contracts after A. Philip Randolph threatened a March on Washington in 1941 to protest continued racism within the U.S. as the nation geared up to fight racial fascism overseas.

So the WMC started sending Black workers to Butte. At first, Anaconda rejected them. Those men then complained to the WMC, but the agency’s representative in Butte dragged his feet, as much of the federal government did in actually desegregating these industries. But Black workers kept coming to Butte. In November 1942, 39 furloughed Black soldiers arrived in Butte to work at the Tramway Mine. This was part of a larger group of 5,000 soldiers with mining experience that was deemed more important than going to North Africa or the Pacific. Anaconda now accepted them. But the workers freaked out. 8,000 members of Butte Miners Union, as Mine, Mill was known locally, refused to work with them. A hate strike was on.

It’s important to learn the details of these strikes and a bunch of them too. I once had a lefty on Twitter challenge me, saying I was defaming the labor movement by focusing on this, saying that the famed Detroit hate strike was the only one. Well, it was the only one he knew. But it was not the only one I knew. Because these happened all the time. One reason it makes sense to have this knowledge at hand is to push back against romantic narratives of American labor and against those who really do want to argue that class matters more than race. Talk about erasing the actual lived experience of American workers!

Now, the BMU leadership and Mine, Mill leadership outright supported Black miners. And they were very angry at the miners for engaging in a hate strike. On November 8, Mine, Mill president Reid Robinson and Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson flew to Butte and held a meeting that really told off the workers, pleading with them to win the war. The workers responded by heckling and booing and ignoring their leaders and the government. Meanwhile, shortly before this Mine, Mill had its international election. Robinson won again, but he came in third in Butte, behind a redbaiter named John Driscoll and a man named James Byrne, who won the city. He was a democratic unionist and in Butte, democratic unionism meant explicitly white unionism. Byrne also called Robinson a commie who was a lackey of the Roosevelt administration who wouldn’t take his men out on strike and of course would allow Black men in the mines.

The government refused to move the Black miners, even though it meant lost copper production. It knew that if it gave into the Butte miners, it would give into white workers across the country, which would mean a lot fewer workers and a lot more lost production than from one hate strike. The government leaned on the Catholic Church to intervene here, hoping the miners would listen to their priests. It didn’t make much difference. By this time, FDR was personally involved, calling major labor leaders to the Oval Office to figure out how to deal with these racial problems. But Butte miners were like, if the government wants to send soldiers into the mines, why can’t they be our own brothers and fathers and sons?

So basically the Roosevelt administration caved to the miners and racism won. It engaged in a sleight-of-hand that said that one mine was as good as another and transferred most of the Black miners to a mine in Nevada. Some did get jobs in the smelter in Anaconda, which had less vile racial politics. A couple of the Black miners remained in Butte and were ready to fight for their jobs, but they just ended up unemployed. The International took care of these guys and continued the fight for interracial unionism more broadly. But against overwhelming local opposition, there wasn’t much they could do. By 1943, there was one Black miner in the 8,000 man workforce, a man named Hi Brown. Brave dude. Basically, the white miners accepted him as a token.

Mine, Mill would go on to continue fighting for interracial unionism, particularly in the Salt of the Earth strike. But even that was basically an all-Mexican workforce. White miners would have little to do with those workers.

This is the 541st post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.