The war on contraception is on

As Mary Zeigler explains, it will be a pincer movement. On the one hand, claiming that Griswold doesn’t apply to minors, and on the other hand making Griswold moot by defining forms of birth control women have control over as “abortifacients”:

But the concerns about birth control’s fate don’t seem so far-fetched anymore. Last week, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals handed a major victory to Jonathan Mitchell, the former Texas solicitor general who has masterminded many of the key post-Dobbs anti-abortion strategies, in a case on birth control that offers a chilling sign of things to come. As I write with Naomi Cahn and Maxine Eichner in an article forthcoming in the Michigan Law Review, conservatives have used arguments about parental rights to attack actions pertaining to school programs on race, sexuality, and gender identity—and to limit travel for abortion. Now, Mitchell is hoping to use a similar strategy to start undermining access to contraception.

The case involves Alexander Deanda, a conservative Christian father angry that the Title X family planning program theoretically allowed his three daughters to confidentially access contraceptive services before turning 18. Since it passed in 1970, Title X has ensured all patients, including minors, access to confidential care, recognizing that this guarantee can affect minors’ choices. Deanda, who did not like this prospect, complained about how the Biden administration was administering Title X, saying it violated his right under both Texas law and the U.S. Constitution to stop his underage daughters from getting birth control without his consent.

[…]

Deanda is just the start of new efforts to roll back contraceptive access, and these efforts are borrowing from a familiar playbook. Activists and attorneys like Mitchell have already experimented with laws that purport to protect minors from “abortion trafficking” when others assist minors in traveling out of state—or “grooming” when school sex education programs teach anything about sexual orientation or gender identity—while suggesting that minors need protection for a reason: abortion is actually dangerous, for example, or being gay or transgender is undesirable. With birth control, conservatives have drawn on the same playbook to argue that contraceptives are dangerous to minors, increasing their risk of cancer or depression, and that parents have a reason to be concerned about their children beyond a belief that premarital sex is wrong.

Republicans are probably right that states won’t pass direct bans on birth control in the near future, or that anyone will pursue an immediate challenge to the right to contraception recognized in cases like Griswold v. Connecticut. But there may be no need for such a move when some conservatives already insist that drugs commonly marketed as contraceptives, such as the morning-after pill, IUDs, and even the birth control pill, are in fact abortifacients.

But Deanda shows that there is a playbook already in place to limit access to contraception for minors and to stigmatize it as unsafe as well as immoral. Deanda’s argument tells us a lot about what is driving part of this campaign: hostility to sex outside of marriage, for adults as much as for minors. It is only when children’s rights are involved, however, that we are currently hearing the quiet part said out loud.

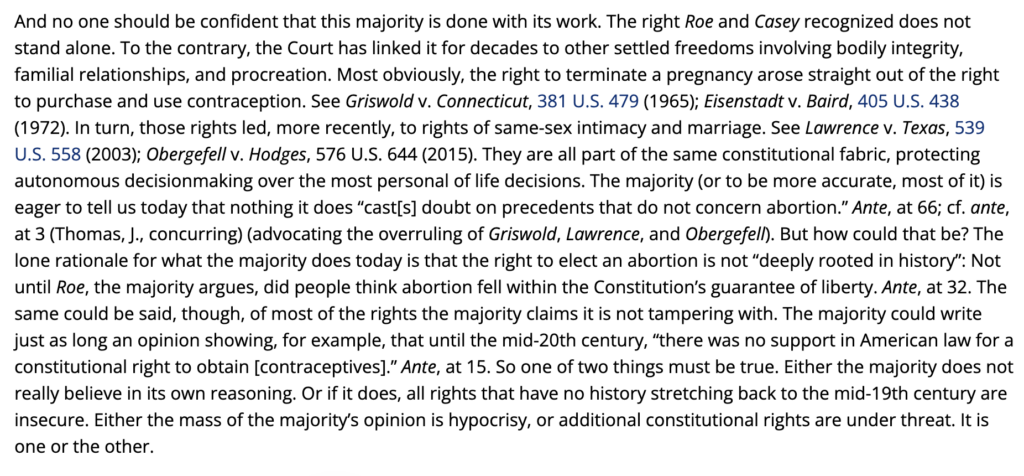

The answer is that additional constitutional rights are under threat, and it doesn’t necessarily have to involve an opinion formally overruling any other precedent. Dobbs unlocks a skeleton key that can immediately be used to undermine other rights.