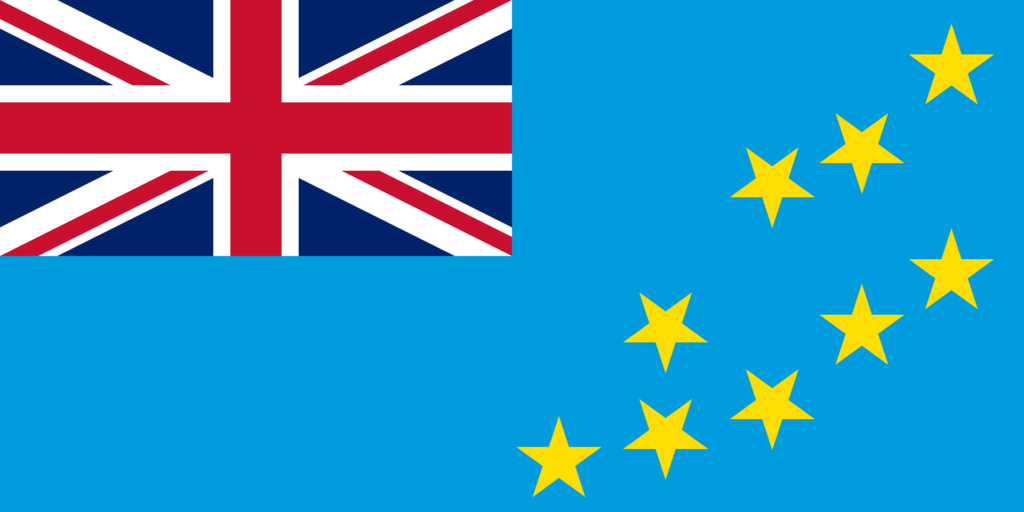

Election of the day: Tuvalu

On September 25, 2008, Kiribati president Anote Tong gave a speech at the United Nations, on the subject of the eventual need to relocate the population of his and other low-lying island nations’ populations due to rising sea levels. While he acknowledged that a suitable territory where nations could be relocated as a whole, thus retaining their territorial sovereignty, would be ideal, the bulk of his speech addressed a more pragmatic set of demands: legal migration and pathways to citizenship and relocation and job-training support for the citizens of his country, to be doled out over the coming decades. This was a bit of a departure from the rhetoric and political position of low-island nations threatened by climate change, shifting from a demand that the global community refrain from collectively drowning our countries, to a demand about how the global community should take responsibility for the consequences of drowning their countries.

This kicked off a minor debate in my own little corner of academia, political theory and philosophy. Shortly after Tong’s speech, the German philosopher and Harvard professor Mathias Risse offered a philosophical justification and defense for Tong’s position, rooted in the the 17th century philosophers John Locke and Hugo Grotius’ conceptions of humanity’s common ownership of the earth. Since the publication of Risse’s paper in 2009, a number of critics, including Avery Kolers, Kim Angell, Cara Nine, and Milla Emilia Vaha, have criticized Risse’s account on a variety of different grounds. A common thread among Risse’s critics is that his account is excessively individualistic–it considered what is owed to Kiribatians as people, but not as a people.

I won’t bore you with the various ins and outs of this philosophical debate; I bring it up because I was struck by the degree to which this philosophical debate is, in fact, playing out in Tuvalu’s parliamentary election. More on that below; first, the basics:

Tuvalu, the smallest UN member-state by population (excluding a corporate headquarters masquerading as a state OK fine, “accuracy” obsessed commenters have pointed out Vatican City is not actually a UN member) at around 11,500 people, will elect a new parliament on Friday, which is actually today, because time zones. Polls close in a few hours. Tuvalu’s parliament has 16 seats, elected by 8 constituencies, with two seats each. (Voters can vote for up to 2 candidates.) Tuvalu is that very rare thing: a functional democratic nation where political parties are not allowed. The Prime Minister is elected by a secret ballot of the 16 representatives. In the most recent election in 2019, then-Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga was returned to Parliament by the voters, but three of his top cabinet ministers were not. The election saw 50% turnover. In what I understand was considered a bit of a surprise, he lost his bid for another term as PM to Kausea Natano by a 10-6 vote. Sopoaga appears to be one of two MPs who have been particularly critical of Natano, the other being Simon Kote, who resigned from Natano’s cabinet in order to campaign for changes in Tuvalu’s constitution. As discerning readers have by now inferred, Tuvalu is situated similarly to Kiribati with respect to sea level rise, if not worse: the highest point in any of the atolls that comprise the island is roughly 15 feet, and sea level rise there is occurring at 1.5-2x the global average rate. Storms are getting worse, as are the now regular floods.

So, what is this election about? It has been dominated by controversies surrounding the Falepili Union, a treaty the Natano administration negotiated with Australia in early November. The final two weeks of the previous parliament were dominated by fierce debate about this treaty prior to the end of parliament. The treaty covers a great deal of territory: it cedes much of Tuvalu’s foreign policy independence to Australia, while Australia provides support for natural disaster relief and other funds, and options for legal migration, job training, and a pathway to citizenship for up to 280 Tuvaluans a year, which could lead to the evacuation of the country over several decades.

Critics see this as an abandonment of Tuvaluan sovereignty in two ways: first, in the immediate sense regarding foreign policy (some see it as an effort to block any future consideration of ties with China–whether Tuvalu continues to have diplomatic ties with Taiwan, or switches to Beijing is a live debate in the country, with Nagano rejecting Beijing’s overtures and remaining committed to their relationship with Taipei). The Albanese administration was troubled by Beijing’s security treaty with the Solomon Islands recently, and has sought to retain their position of regional influence over small Pacific Island nations in the face of increasingly strong diplomatic efforts on that front from China. Secondly, it is seen to threaten Tuvalu’s sovereignty by accepting a version of Risse’s deal that may threaten the continuation in perpetuity of a Tuvaluan institutional existence and national identity. A Constitutional change just prior to this agreement asserts perpetual maritime rights over the current patch of ocean they claim them, even if the land disappears, as an attempt to preserve some vestige of a Tuvaluan institutional identity even if their citizenry is absorbed by Australia, but critics understandably worry that isn’t enough.

Australia’s “veto power” has upset some Tuvaluans, who believe their vulnerable nation has been bullied into ceding sovereignty in exchange for a safe harbor.

Adding to their anger: The treaty does not require Australia, one of the world’s biggest fossil fuel exporters, to take more action on global warming — the root cause of Tuvalu’s woes. (Australia was, however, among the nearly 200 countries that agreed at COP28 earlier this month to transition away from fossil fuels to avert the worst effects of the climate crisis.)

“If Australia believes in providing a humanitarian pathway for Tuvaluans, the best way they can do that is to reduce their emissions, stop opening up coal mines, stop exporting coal,” said Enele Sopoaga, Tuvalu’s opposition leader, who has pledged to tear up the deal if he wins office. “It’s shameful for Australia to suddenly jump up and say, ‘Tuvalu, I can offer you a saving hand.’”

Local activists have similar concerns.

“There are many young Tuvaluans who are very excited about this treaty, about moving to Australia,” said Richard Gokrun of the Tuvalu Climate Action Network. “But this is not a solution. It won’t stop the existential threat we are facing. It won’t stop the sea level from rising.”

Sopoaga accuses Australia of “meddling” in the election. The visas, he said in an interview, were “carrots” for voters, but the treaty was really “all about China.”

Simon Kofe, who gave up an Australian passport to run for Parliament and who served as a minister in Natano’s government until recently, also criticized the agreement. While the two countries share many values, Tuvalu shouldn’t be dragged into a geopolitical tussle, he said, noting that Tuvaluan islands that hosted U.S. airfields in World War II were bombed.

“We need to be wise in the decisions we make today because if a conflict was ever to break out again, then Tuvalu could be a target,” he said. “Our interests may come into conflict with Australia’s interests, and our interests might be sacrificed.”

Yet Kofe — who addressed COP two years ago while knee-deep in water, and who has been the architect of key initiatives including the constitutional reforms and digital clone — wants the next government to revise, rather than scrap, the treaty.

The treaty adopted his idea of Tuvalu’s enduring statehood, which was a victory. But it didn’t cut Australian emissions or provide Tuvaluans with visa-free travel.

“If you’re calling us family, then you should treat us like it,” he said.

Whether the new parliament returns Nagano or elects Sopoaga or Kote as the new Prime Minister will play a major role in how this treaty is revised, or if it’s scrapped altogether. Nagano appears to be the “moderate revisions” option, Kote the “major revisions” candidate, and Sopoaga for scrapping it. From where I sit, the odds of Tuvalu finding a way to retain something that resembles sovereignty as commonly understood seem quite long, but I can’t really fault them for trying. The Friday voting period is ending right about now (pesky time zones again), but of course we may not know who the new PM will be for a while, although we should know if any of the three contenders failed to retain their seats soon enough.