The shock of the old

Here are a couple of interesting essays, by Ted Gioia and Colin Marshall, on the striking extent to which old music, in pretty much every popular genre, is increasingly overwhelming the cultural and economic space once filled by new music.

The statistics Gioia assembles in this regard are pretty compelling:

According to MRC Data, old songs now represent 70% of the US music market.

Those who make a living from new music—especially that endangered species known as the working musician—have to look on these figures with fear and trembling. . .

Consider these other trends:

- The hottest area of investment in the music business is old songs—with investment firms getting into bidding wars to buy publishing catalogs from aging rock and pop stars.

- The song catalogs in most demand are by musicians in their 70s or 80s (Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen, etc.)—if not already dead (David Bowie, James Brown, etc.).

- Even major record labels are participating in the shift, with Universal Music, Sony Music, Warner Music, and others buying up publishing catalogs—investing huge sums in old tunes that, in an earlier day, would have been used to launch new artists.

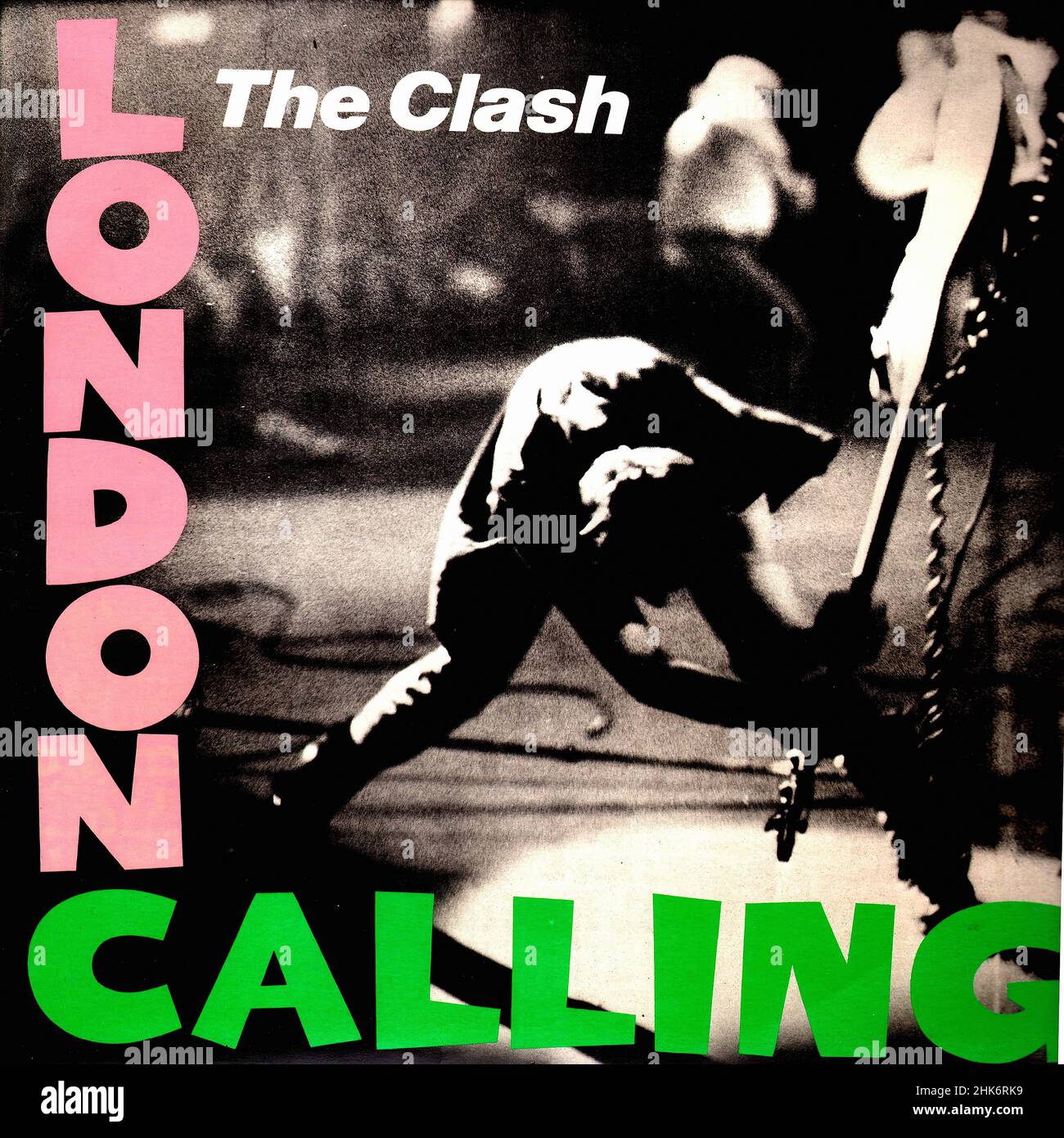

- The hottest technology in music is a format that is more than 70 years old, the vinyl LP. There’s no sign that the record labels are investing in a newer, better alternative—because, here too, old is viewed as superior to new.

- In fact, record labels—once a source of innovation in consumer products—don’t spend any money on research & development to revitalize their businesses, although every other industry looks to innovation for growth and consumer excitement.

- Record stores are caught up in the same time warp. In an earlier day, they aggressively marketed new music, but now they make more money from vinyl reissues and used LPs.

- Radio stations are contributing to the stagnation, putting fewer new songs into their rotation, or—judging by the offerings on my satellite radio lineup—completely ignoring new music in favor of old hits.

- When a new song overcomes these obstacles and actually becomes a hit, the risk of copyright lawsuits is greater than ever before. The risks have increased enormously since the “Blurred Lines” jury decision of 2015—with the result that additional cash gets transferred from today’s musicians to old (or deceased) artists.

- Adding to the nightmare, dead musicians are now coming back to life in virtual form—via holograms and deepfake music—making it all the harder for a young, living artist to compete in the marketplace

The whole essay is worth reading. The flip side of all this is that the amount of accessible new music is at levels that would have been incomprehensible even a generation ago. One of my brothers is a professional musician who runs a recording studio, and tells me that 60,000 songs are uploaded to Spotify every day. How is it possible to even begin to explore the new, when there’s just so much of it? (Erik’s heroic efforts in this regard only emphasize for me the impossibility of the situation).

On yet another hand, there’s so much of everything, old and new, that nobody listens anymore to albums in the form that they were intended to be heard. One obsessive compulsive solution to this problem is readily available however:

My own musical life in this decade offers an extreme example, dominated by the likes of the Beatles, the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. This resoundingly un-idiosyncratic list is the result not of an ossified musical incuriosity but of a deliberately undertaken project: whereas Gioia listens to two or three hours of new music every day, I’ve made a daily habit of listening to “old” music—music by artists who began their careers in the nineteen-sixties and have made the largest, most obvious marks on popular culture. Working my way through their entire studio discographies, I take one album per week and play it once every day, straight through. This method (which I used most recently to navigate the nearly half-century-long catalogue of David Bowie) requires both an obsessive streak and a certain degree of patience: the studio albums of Dylan alone, which number thirty-nine as of this writing, took up most of a year.

I love me some Bob Dylan, but you would have to pay me a lot of money to listen to all 39 of his studio albums straight through, let alone each one of them once a day for a week for nearly a year (People are strange. Ha got you!).

I have a lot more to say about this but am out of time this morning so go your own way (got you again!) on the topic.