Good News?

From comments in the last few Ukraine posts it seems that folks want some good news, and there is some good news. The ISW assessment has a good rundown of the what’s going well and what’s going not-so-well.

At the Front

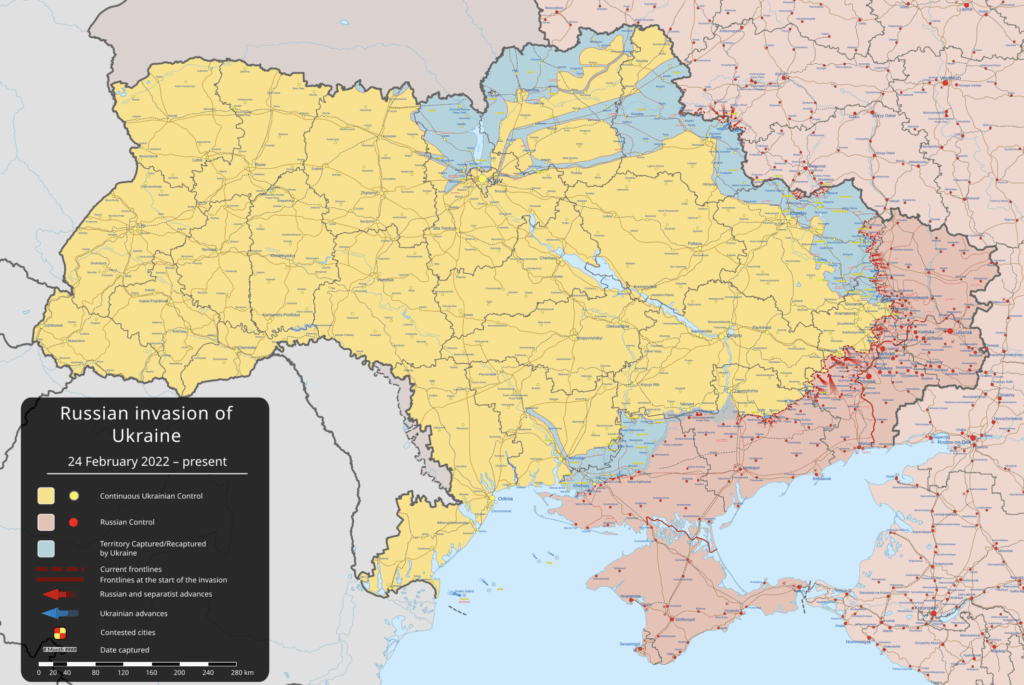

There’s some reason to believe that the Pokrovsk infiltration is being dealt with. This is a pretty interesting case from a military history perspective. Broadly speaking, the “lines” that we see on a battle map are not exactly lines; they are distributions of infantry and other personal at regular and irregular intervals in a pattern that can be best described as “line like,” Since World War I (although you can see this in development even at battles like Gettysburg and Vicksburg) that line has become ever more porous, with density of infantry at the front the “line” steadily decreasing. The range and lethality of weapons on both the offense and defense enables this trend; a defensive position can be held with fewer soldiers because those soldiers have long-range lethal direct fire weapons and can call in artillery bombardments, and it’s best to try to hold it with only a few soldiers because enemy artillery can wreak havoc even on strong points. But this is why “infiltration” tactics are so critical on the modern battlefield. Infantry can stealthily infiltrate through a defensive “line,” and essentially reduce strong points by outflanking them. Conducted effectively, infiltration operations can open a breach in a “line” that mechanized or dismounted forces can then exploit. The question then becomes whether the defender can mass reinforcements fast enough to seal the breach before it does real damage. The Allies in the spring and summer of 1918 managed to seal the German breach before it could inflict decisive damage; the Allies in the spring of 1940 failed to do so.

The important thing to remember, however, is that as density drops it becomes easier for infantry to simply walk through an enemy “line.” Density along the Ukrainian front is very, very low because the Ukrainians are infantry poor and drone rich. Drones are doing the job of monitoring Russian infiltrations and blunting them, hopefully reducing the need for infantry. Pokrovsk is what happens when the infiltrations are insufficiently monitored and insufficiently blunted, and there had been questions about how effectively the Ukrainians would be able to mass reinforcements in order to seal the breach. It looks (and I caution that anything can change quickly) that the sealing of the breach is happening, which is good news although we need to be cognizant of events elsewhere on the front.

Russian losses really are significant, and they tend to pick up as Russia collects more territory. Note that I prefer not to regard the deaths of young Russian men as “good news,” but rather “good news for Ukraine,” which is a distinction that may not matter for others but matters for me.

The Economic War

Even Quincy now acknowledges that the Russian economy is in a severe situation.

Russia’s sanctions-defying economy, propelled higher by the Ukraine war, is suddenly coming back down to earth.

Fueled by massive military spending and steady oil exports, Russia recorded some of the highest growth rates among major economies over the past two years. But in recent weeks economic indicators have been flashing red: Manufacturing activity is declining, consumers are tightening their belts, inflation remains high and the budget is strained.

Russian officials are now openly warning of the risks of a recession, and companies from tractor producers to furniture makers are reducing output. The central bank said Thursday that it would debate cutting its benchmark interest rate later this month after lowering it in June.

It’s worse that that for Russia in the long term, because there’s not much reason to think that oil prices are going to increase anytime soon, and because the manufacturing mobilization around military equipment is basically a dead end. Military spending generates growth because it activates widespread economic activity, but it does not increase productivity per worker or unit of capital and does not facilitate long-term technological growth. Russia is getting very good at building weapons that the Indians, Chinese, and even Ukrainians can build more cheaply for the international market, and can sell without the headaches associated with buying from Russia.

The War for Popular Opinion

Alaskans are doing a good job of protesting Putin, an indication of general pro-Ukrainian movement in US popular opinion:

Overall, 54 percent of respondents said the U.S. should stay the course for as long as it takes, compared to 48 percent in July and August 2024, 45 percent in September and October 2023, 43 percent in June 2023, and 38 percent in March and April 2023. (Note that we also asked this question in March 2025, but only of those who said “oppose” or “I don’t know” to the question: “Do you support or oppose the decision?” This subset represented roughly 44 percent of all respondents). This question had an unsurprising partisan divide, with much of the rise in support coming from Democrats, with 74 percent of respondents from that party saying they want to stay the course “as long as it takes,” compared to 63 percent a year ago. Only 36 percent of Republicans said the same, compared to 37 percent a year ago.

Very few Americans are sympathetic with Russia, and US support for Ukraine has not “exhausted” the American people in any meaningful way. The Republican Party is controlled by a faction (not even generally popular within the GOP) that views Russia in ideologically favorable terms, and that faction is now setting policy. The conversation over US support for Ukraine would be much healthier if we could acknowledge these points.

Ukrainian Democracy

I haven’t followed all of the ins and outs associated with the Ukrainian anti-corruption debate, but two points are worth making. The first is that the moves made by the Zelensky administration to reduce anti-corruption efforts and judicial independence were, in fact, actually bad. As Paul Hockenos indicates, this is why it actually matters to have a US administration saying “democracy is important,” and holding the Ukrainian government to account; it’s rough to perform democracy in the middle of a war and the temptations are many. Second, the fact that there was massive pushback against a popular war president is in fact very good news for the future of Ukrainian democracy.

After a public outcry and pressure from the European Union, a new law is now in force in Ukraine restoring the independence of state agencies investigating corruption.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy introduced this bill after facing his first major domestic political crisis since Russia’s full-scale invasion three and a half years ago. He and Ukraine’s parliament reversed course after approving a previous bill to place anti-corruption agencies under a Zelenskyy-backed prosecutor.

Thousands of Ukrainians took the streets in protest, calling it an authoritarian move.

“It is very important that the state listens to public opinion and hears its citizens,” Zelenskyy said in a video address on Thursday. “Ukraine is a democracy for sure. There is no doubt.”

Shit like that doesn’t happen in Russia. Hell, it barely even happens in the US.

Wrap

So that’s your good news. There is also bad news, captured best I think by the term “hopeless but not serious.” Regardless of how Pokrovsk works out, the Russians are gaining territory. Russian casualties are severe but Russia has demonstrated a capacity to regenerate those losses more effectively than Ukraine. Ukraine can blunt the Russian strategic bombing offensive but cannot defeat it. There is little indication that Ukraine is going to be able to recapture significant territory from Russia under any foreseeable circumstances. Russia’s army might collapse; Russia’s economy might collapse; public support for Putin might collapse. Ukraine cannot win a military victory unless one or more of those three things happens, and none of them seem to be very likely under the conditions that we’re witnessing today. In short, there’s a very good chance that Russia can stay irrational for longer than Ukraine can stay solvent. This is why what’s happening in Alaska (summit, negotiation, fly fishing jaunt, call it what you will) matters a great deal for the future of Ukraine.