The lavatories of democracy

Jane Mayer has a great piece about democratic decline in US statehouses:

Click acknowledged that the story of the ten-year-old rape victim is discomfiting, adding that “we all have a visceral reaction” to such a scenario, “regardless of one’s political leaning.” But the news had not made him question his position; rather, he questioned the girl’s story, calling it “suspicious,” and noting that the incident “fit too neatly” with the pro-choice agenda. (According to law-enforcement authorities, a twenty-seven-year-old Ohio man confessed to twice raping the girl when she was nine. He has since pleaded not guilty.) Click also echoed an argument made by Ohio’s Republican attorney general, Dave Yost, who claimed that the ten-year-old—“if she exists”—would have qualified for the new statute’s medical-emergency exception. This assertion, however, has been disputed by various doctors, including State Representative Liston. “I don’t know the child’s health condition,” she acknowledged to me. “But it’s hard to say that simply because she is young she would meet the requirement of risk as defined by the new law.” Mortality rates are generally higher for pregnant girls who are younger than fifteen, but, Liston said, “there’s nothing in the law that states that age is a sufficient exception.”

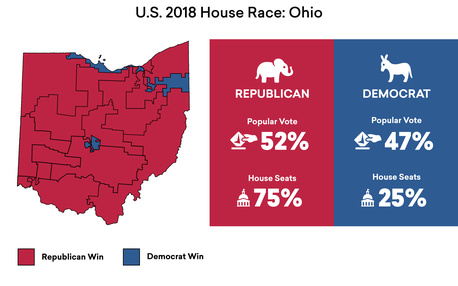

Click, who is a close ally of the Republican congressman Jim Jordan, is one of Ohio’s most extreme legislators, but he’s hardly out of place among the General Assembly’s increasingly radical Republican majority. Niven, the University of Cincinnati professor, told me that, according to one study, the laws being passed by Ohio’s statehouse place it to the right of the deeply conservative legislature in South Carolina. How did this happen, given that most Ohio voters are not ultra-conservatives? “It’s all about gerrymandering,” Niven told me. The legislative-district maps in Ohio have been deliberately drawn so that many Republicans effectively cannot lose, all but insuring that the Party has a veto-proof super-majority. As a result, the only contests most Republican incumbents need worry about are the primaries—and, because hard-core partisans dominate the vote in those contests, the sole threat most Republican incumbents face is the possibility of being outflanked by a rival even farther to the right. The national press has devoted considerable attention to the gerrymandering of congressional districts, but state legislative districts have received much less scrutiny, even though they are every bit as skewed, and in some states far more so. “Ohio is about the second most gerrymandered statehouse in the country,” Niven told me. “It doesn’t have a voter base to support a total abortion ban, yet that’s a likely outcome.” He concluded, “Ohio has become the Hindenburg of democracy.”

It’s not just that gerrymandering can allow the party with the minority of the votes to get a majority of the legislature — in Ohio in 2022, Republicans would win fair elections more often than not. It’s that it allows Republican governments to enact virtually whatever they want, irrespective of its popular support, because they’re almost entirely insulated fro electoral backlash. (A Democratic governor can stop new stuff from the ALEC assembly line being passed, if her veto can’t be overridden, but can’t get the old laws off the books.)

As I’ve said before, Rucho v. Common Cause is one of the very worst decisions in the ignominious history of the United States Supreme Court, and in terms of its concrete material consequences is worse than even Shelby County.

People interested in the subject should also check out my colleague Jake Grumbach’s new book, which I’m hoping to discuss with him here at some point.