Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,123

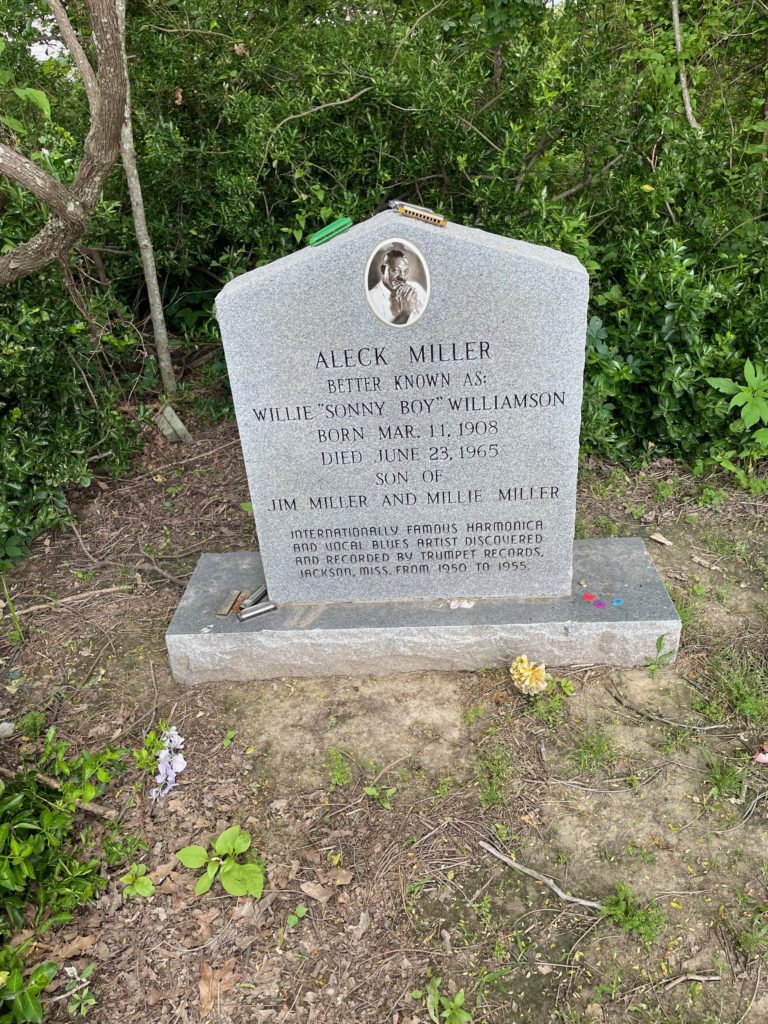

This is the grave of Sonny Boy Williamson.

Born at some point in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century and probably either in Greenwood or Glendora, Mississippi, Aleck Miller, later known as Sonny Boy Williamson, was a strange dude. He refused to say how old he was. This 1908 date on the gravestone is merely a guess. Somewhat educated guesses have ranged from as early as 1897 to as late as 1912, which given that range is nearly an entire generation, demonstrates just how little is really known here.

I guess the specific date of birth or age doesn’t really matter. What is known is that like nearly every other Black person in Mississippi, Miller grew up very poor. His parents were sharecroppers. His given name was actually Ford, but then his mother married a man named Jim Miller and the boy took his stepfather’s name. However old he actually was, he stayed around his parents until the early 1930s. At that point, he began to travel around the Delta playing music. He was a masterful harmonica player. He knew Robert Johnson and Big Joe Williams and Elmore James and the other great blues musicians of that fertile period in the Delta. During these years, he became known for his harmonica tricks and generally well-developed stage persona. He took on different stage names during these years, such as Rice Miller and Little Boy Blue.

In 1941, Miller was hired to play on the King Biscuit Time Show out of KFFA in Helena, Arkansas, just across the Mississippi River from Mississippi. This was a show dedicated to Black audiences. It was here that took on the name Sonny Boy Williamson. Now like everything else about the man, this was a bit odd. That’s because there was already a well-known Sonny Boy Williamson who also played the harmonica, who had come out of Tennessee and was making a very good career for himself in Chicago. Miller simply stole his name to confuse people and gain himself more publicity. Some have argued that his claims to have been born in the 19th century were attempts to predate Sonny Boy Williamson I and back up his other claims that he originated the name. But these were lies.

Well, in any case, Williamson II might have been a sharper and strange guy, but he was good at his instrument. By 1948, he had moved to West Memphis, Arkansas and had his own radio show in Memphis itself. At this point, he was living with his good friend Howlin’ Wolf and he was a pretty big deal in the blues world. Remember that by this point, a lot of these blues guys were already being forgotten about. The Great Depression had killed the recording industry and a lot of these people hadn’t really recorded after the mid-30s or so. But Williamson brought his Delta and Helena crew up to Memphis to be on what became an important radio show on KWEM. He funded the show by pitching Hadacol, which is basically booze but legal in the dry counties of the South because it was “medicine,” on the show. People such as Elmore James, Arthur Crudup, and Robert Nighthawk frequently appeared on the show.

All of this got Williamson more attention and in 1951, Trumpet Records signed him to a recording deal. Trumpet is an interesting story in itself. Run by a white woman named Lillian McMurray out of Jackson, Mississippi, Trumpet realized that the region had all these great musicians who had no access to recording contracts. Her husband ran a furniture show and decided they could sell records out of it as well. So she went about signing artists, not only blues musicians but other pre-rock Black musicians playing boogie-woogie and other dance forms. He did a bunch of recordings for Trumpet, but that label went bankrupt and had to sell its catalog. That said, it did not let these artists die but rather sought to connect them with real labels. That led Williamson to Chess, based out of Chicago. The Chess Brothers loved Williamson and so brought him up to the big city. He developed a solid fan base there going back to 1953, when he played the harp in Elmore James’ band in the city. Chess had a subsidiary named Checkers Records (eyeroll) and on that label, Williamson recorded about 70 songs over the next few years. Most of these were singles. Williamson’s first album, Down and Out Blues, came out in 1959 and consisted of some of his previous recordings. This was a pretty common practice as the record industry moved to long-play albums with new technology.

Like a lot of these blues guys, Williamson found his real adoration among young British men, who were forming bands. Much more so than white Americans of the era, these Brits were obsessed with this tradition coming out of America, one supposes given that the British had nothing like this at all and the appeal of Black music was, yes, the appeal of authenticity, but it was also the appeal of good. Williamson was all about making money when he could, so he rushed to Europe to play. Unlike the guys a generation older than he, Williamson was also still in reasonably good health and young enough to do this. British blues bands loved backing him up. What he thought about the quality of those bands, I do not know, but he certainly like the adoration and the cash. He recorded an entire album with The Yardbirds and recorded with The Animals too. He stuck around Europe as much as he could during these years and ended up appearing on a Roland Kirk live album from Copenhagen in 1963 playing his harp.

Williamson came back to the U.S. after that and restarted his King Biscuit Time show in Helena. Of course now he was a bigger deal than before. He could afford nice clothes and if he needed money, he could always go play in Europe. But one day, in 1965, he didn’t show up for the show. That’s because he had died of a massive heart attack. He might have been 52 years old but it’s impossible to know.

In the aftermath of his death, there were tons of releases of his material. More was released after he died than before. His album with The Yardbirds came out in 1966 and only increased the interest in his work. Chess followed that up with The Real Folk Blues the same year, made up of cuts recorded between 1957 and 1964 for that label. The Animals released their recordings with him in 1972. Interestingly, the set that perhaps got the most attention was the 1969 release Bummer Road, in which the album included an 11 minute outtake from the recording session with Williamson and Leonard Chess bitching each other out over the recording of a song and this became the first blues album to have to have a sticker based on profanity. Really, this is a stunt release but it’s an interesting artifact all the same.

Sonny Boy Williamson is in Whitfield Baptist Church Cemetery, Tutwiler, Mississippi, which I can assure you was not easy to find. You may remember a month ago or a bit more when I was mentioning raising some grave funds for this trip. Well, this is the first grave I’ve done off that trip and I hope it was a good one for you.

The grave itself was placed up by Lillian McMurray in 1977. She didn’t know his birth date either and came up with this date for some reason.

Let’s listen to some Sonny Boy Williamson.

If you would like this series to visit other blues legends, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. B.B. King is in Indianola, Mississippi and Muddy Waters is in Alsip, Illinois. Previous posts in this series are archived here.