Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,114

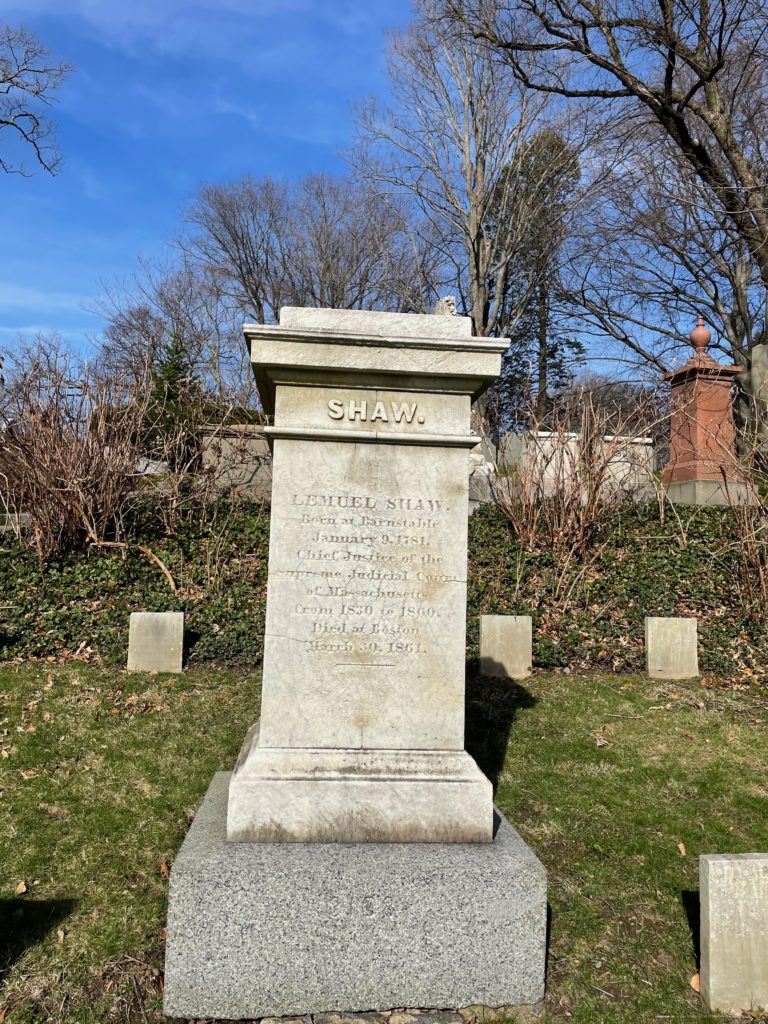

This is the grave of Lemuel Shaw.

Born in 1781 in West Barnstable, Massachusetts, Shaw grew up as part of the old Puritan world, with family who went back to the very beginnings of white colonization. He went to Harvard, as any son of a minister from that background should. He graduated in 1800, taught a bit, and edited a Federalist newspaper. In 1801, he decided to go into the law. He moved to New Hampshire and passed the bar there in 1804, but came back to Massachusetts shortly after and opened his practice in Boston. He was serious about the law. He was of course a quite political man–a very conservative Federalist and then a close friend of Daniel Webster with his strong Whig politics. However, one key thing Shaw varied on with his friends was his support of free trade during a very protectionist period, one where the tariff was often the biggest issue in politics, one that often stood in as a proxy for the slavery no one wanted to talk about.

Like many leading lawyers, Shaw went into electoral politics as well, though never with serious ambitions to higher office. He started in the state legislature in 1811 and served on and off in that body and the state senate through 1829, though never for more than a couple of years at a time. He was a delegate to the state constitutional convention in 1820 and held a bunch of offices in Boston city government as well. He also drafted the city’s first charter in 1822, one that remained in use for nearly a century.

In 1830, Shaw agreed to become Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court. He didn’t want to take it because it was a huge salary reduction from his private practice. But Daniel Webster was like, you have enough money, do it for the public good. So Shaw agreed and stayed in the office until he was a very old man.

Shaw had an outsized role in the history of the American judiciary, more than nearly any other jurist who did not serve on the Supreme Court. The context is a big reason for this and Massachusetts is critical to the decades before the Civil War for two reasons. First, it was the center of American manufacturing. Second, it was the center of American abolitionism. Shaw would play a leading role in deciding cases related to both.

Shaw was someone, like so many Massachusetts elites, who thought the rise of industrialization was PROGRESS and all things must fall before that god. Naturally enough, the rise of industrial capitalism led to a lot of lawsuits. For example, what happened if a mill dammed a river and then the backing up water caused erosion to farmland upstream or eliminated a shad run that people relied upon? These were court cases around these issues (Shaw may have in fact been involved in them but I’m not sure about this). Courts in New England consistently ruled that what mattered was progress. The greater economic purpose–defined by what was going to make people the most money–mattered more than anything else. In many ways, this makes Shaw one of the unique villains of American labor history.

On October 30, 1837, Nicholas Farwell, a train engineer toiling for the Boston and Worcester Rail Road Corporation fell off a train while at work and had his hand crushed by the train. Farwell sued the company for damages. The 1842 decision by the Massachusetts Supreme Court set into place the doctrine of worker risk. This decision set a vitally important precedent in American labor history that the worker voluntarily took on risk when he or she agreed to be employed on the job. Over the next century, tens thousands of Americans died on the job with employers doing nothing.

Farwell had done nothing wrong. While he was working, a switchman messed up and the train derailed, which is how Farwell was thrown. Rather than accept his fate, which was not good as a disabled individual in a world without a social safety net, Farwell sued the company for $10,000. In his decision in Farwell v. Boston and Worcester Rail Road Corporation, Massachusetts Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw disagreed. Shaw claimed that Farwell was personally responsible for the risk of work. Risk was what someone took on by taking a job as well as the opportunity of bettering oneself in the new industrial system. Because Farwell was paid more than other railroad workers, he was already being compensated for the higher risk of his work. Shaw called the $2 a day Farwell made, a “premium for the risk which he thus assumes.” Shaw might sue his “fellow servant” who made the mistake that led to his fall but the company was immune to lawsuits of this kind.

What Shaw did was effectively take employers off the hook for injuries caused on the job. It would take a century to fix this problem, to the extent that it is really even fixed today.

On the other hand, Shaw was not an anti-labor extremist. Commonwealth v. Hunt originated with the Boston Journeyman Bootmakers’ Society, an early craft union. A worker named Jeremiah Horne agreed to do extra work on a pair of boots without charging for his labor. The Society fined Horne. He refused to pay, but his master did. But Horne was a jerk and kept breaking the rules. Finally, the Society demanded the master fire him and he did. Horne went to the Suffolk County Attorney to complain. He decided to prosecute the Bootmakers’ Society for unlawfully engaging in a criminal conspiracy to impoverish non-union members and their bosses. The trial began on October 14, 1840 and ended eight days later. The Bootmakers had a strong defense, crafted by the leading Boston Democrat Robert Rantoul, who made a case that such combinations were common and unexceptional. The judge, Peter Oxenbridge Thacher, was however a rabid pro-business conservative Whig and told the jury that such actions would “render property insecure, and make it the spoil of the multitude, would annihilate property, and involve society in a common ruin.” So the workers lost. But they appealed and the case went to the Massachusetts Supreme Court. The laws really were against workers, which often banned the strike entirely.

Shaw ruled for the workers. He wrote, “We cannot perceive, that it is criminal for men to agree together to exercise their own acknowledged rights, in such a manner as best to subserve their interests.” He issued this really a mere week after the Farwell case!!! It wasn’t a sweeping victory for workers. This only applied if their actions remained legal and their ends reasonable. Basically, it means-tested each strike and so long as it stayed within proper boundaries, that was OK. In other words, strikes for wages and hours might well be legal but strikes to challenge capitalism were not. Shaw took Rantoul’s legal reasoning almost fully, noting that there were no laws in Massachusetts against raising wages and so the appeal to English common law where there was precedent for that was irrelevant. Some have speculated that Shaw, a Whig himself, made a politically expedient decision and didn’t want to have a riled up Boston working class voting overwhelmingly for Democrats in the 1844 election. In any case, we don’t really know why he gave labor a rare favorable ruling that so clearly articulated the right to strike.

Shaw generally tried to take a moderate position on the slave cases he saw, but facing a South that demanded full fealty to the Slave Power, he became a villain down there. In Commonwealth v. Aves, he ruled that slaves taken into Massachusetts weren’t fully free but they couldn’t stay very long, which angered abolitionists but really infuriated the South, which thought it had the right to take its property wherever it wanted. On the other hand, he also ruled in favor of school segregation. He also enforced the Fugitive Slave Act, despite his personal opposition to slavery. Shaw would not bow to public pressure and release escaped slaves caught in the state, infuriating abolitionists.

Shaw also was the presiding judge in Commonwealth v. Hunt, which went far to define what murder really meant in criminal cases and established much of the nuance around these issues in the legal world (those of you who are lawyers may well understand this case more than I do). Related to his pro-industry case in Farwell, in Brown v. Kendall in 1850, he placed the greater proof for liability in lawsuits on the plaintiff rather than the defendant. This is probably a good thing overall, but also reinforced industry’s ability to say it wasn’t negligent when workers were hurt or killed. Somewhat counter to Farwell, he ruled in Commonwealth v. Alger, a case around police powers, in a way that laid some of the legal groundwork for the modern regulatory state, soon about to end thanks to the current Court.

Also, Herman Melville married Shaw’s daughter and Typee is dedicated to the jurist.

Shaw only left the bench in 1860, as his health was in decline. He died in 1861, at the age of 80.

Lemuel Shaw is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

If you would like this series to visit other influential judges who never served on the Supreme Court, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Learned Hand is in Menands, New York and Skelly Wright is in Arlington. Previous posts in this series are archived here.