Let’s Not Put Too Much Pressure on Amazon Workers to Lead the Labor Movement

I have one point to make and one axe to grind and they are related.

The point is that organized labor has had so few wins in recent decades that every time there is something that looks like a victory or even not a victory but some kind of respectable defeat, the workers there are seen to have huge lessons for the labor movement that everyone needs to follow. The problem with this is obvious–the small sample size means that we are seeing each of these out of the context by which we need to understand just what was going on.

The axe to grind is that no group of people are worse about making unreasonable claims out of a single victory than labor historians and other labor scholars, all of which should know better. One of these days, when I really genuinely don’t care about anyone liking me in the entire field, I am going to write some article about the horrible predictions about cheerleading labor historians that are always wrong. A really classic example of this came out of the Wisconsin teachers movement after Scott Walker decided to destroy public unions. Of course, teachers didn’t even win this. But in a book published soon after called Labor Rising, historian after historian made claims like “now we’ve got the employers where we want them!” Uh, no we don’t. And that was obvious by the time the book was published a year later. I mean, it automatically dated the book and it is also embarrassing. One thing that may surprise regular people is that I am not per se well liked in the labor history community because I am grumpy about it all and not just yelling “solidarity!” and “The people united will never be defeated!” as if those were useful actions. Well, you have to call it as you see it and I will never ever be a hack for anyone.

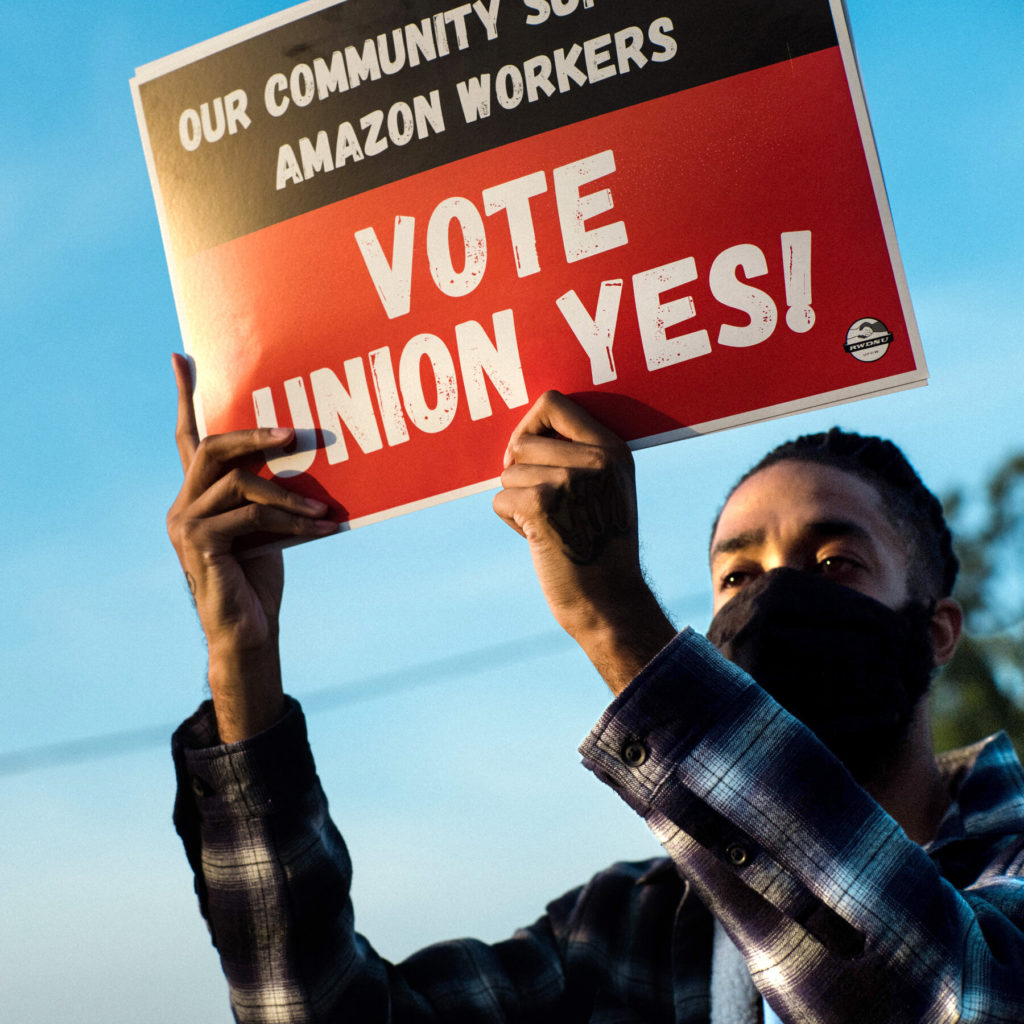

The reason I bring this up now is that both of these things are happening in the aftermath of the Amazon union vote on Staten Island. Now, it’s not impossible that this is the one thing that turns around the labor movement. This is highly unlikely, but it’s possible. It’s also amusing to see internet labor lefties be like “I hate that motherfucker Joe Biden, but goddamn it his NLRB was critical here and I hate to admit that.” Well, OK then. But it is strikingly unhelpful to assume that because this one election was won in a particular way that the entire labor movement has to fall in line. Why this really matters here is that the workers chose to go it alone and not with an established union, which makes it much harder to win a contract, if not win the initial vote. We’ll see how this goes, but it’s far from clear to me that the response should be fewer professional organizers. And yet, here’s a whole Times piece about this:

After the stunning victory at Amazon by a little-known independent union that didn’t exist 18 months ago, organized labor has begun to ask itself an increasingly pressing question: Does the labor movement need to get more disorganized?

Unlike traditional unions, the Amazon Labor Union relied almost entirely on current and former workers rather than professional organizers in its campaign at a Staten Island warehouse. For financing, it turned to GoFundMe appeals rather than union coffers built from the dues of existing members. It spread the word in a break room and at low-key barbecues outside the warehouse.

In the end, the approach succeeded where far bigger, wealthier and more established unions have repeatedly fallen short.“It’s sending a wake-up call to the rest of the labor movement,” said Mark Dimondstein, the president of the American Postal Workers Union. “We have to be homegrown — we have to be driven by workers — to give ourselves the best chance.”

The success at Amazon comes on the heels of worker-driven initiatives in a variety of other industries. In 2018, rank-and-file public-school teachers in states like West Virginia and Arizona used social media to plan a series of walkouts, setting in motion one of the largest labor actions in recent decades and forcing union leaders to embrace their tactics.

White-collar tech workers have organized protests at Google and Netflix over issues like sexual harassment and prejudice toward transgender people. At colleges like Grinnell and Dartmouth, workers have recently formed unions that are unaffiliated with existing labor groups.

And at Starbucks, where workers have voted to unionize 10 corporate-owned stores and filed for elections in roughly 150 more over the past six months, the campaign has largely expanded through worker-to-worker interactions over email, text and Zoom, even as it is being overseen by Workers United, an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union.

Nonunion Starbucks employees typically receive advice from their newly unionized counterparts, then meet with co-workers in their stores, distribute union cards, decide whether and when to file for an election and respond to media inquiries — responsibilities that professional union staff members often carry out in traditional campaigns.“

I can give my opinions — experience means something, but living it means more,” said Richard Bensinger, an organizer for Workers United, referring to the difference between organizing as an outsider and working at a company.

This overstates a lot–it notes that SEIU is behind the Starbucks campaign and don’t underestimate the power of that union. Also, the West Virginia teachers movement was “outside” the union, but really in name only and mostly for legal reasons. But ultimately, the answer here is “maybe.” I’m not saying this is incorrect. I’m saying that I don’t know and I’m saying that no one else knows either, which is really the important issue. The idea that it is the union itself that is getting in the way of victories is a bit hard for me to accept. The Retail Workers nearly won in Alabama and that’s simply a much harder place to organize than Staten Island. It’s just hard to know. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t encourage independent unions. Workers should do what they think is right and we can move forward from there. But I think it’s far from obvious that a more decentralized union movement would be more successful.

As for the labor historian issue, we are seeing this overstating the importance because you want it to be true pop up again. Ruth Milkman is a very fine historian with an august career and I have nothing to say negative against her or her work. But I don’t think it helps anyone to compare the Amazon victory to the Flint Sit-Down Strike or the United Farm Workers struggle.

The unlikely triumph of the ALU has some parallels to the United Farm Workers’ early successes. As Marshall Ganz, author of Why David Sometimes Wins, argued, there are times when resources matter less than resourcefulness, or what he calls “strategic capacity.” Indeed, the UFW succeeded on a shoestring budget with a range of innovative tactics, while a far better funded AFL-CIO effort to organize farmworkers flopped.

In some ways the ALU’s campaign was remarkably conventional. It focused on winning a traditional labor representation election via the creaky old machinery of the NLRB. But it also had some innovative aspects. The ALU made extensive use of social media, especially TikTok and Telegram. They distributed free food and even marijuana (now legal in New York). The organizers also actively aimed to win over workers of color and immigrants.

The use of social media and the intersectional approach reflected the fact that the ALU leaders are relatively young, part of the millennial generation (and joined by the even younger Gen Z), many of whom entered the labor market in the aftermath of the Great Recession. This was the group that led Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter; more recently they have been bitten by the union bug. Young workers, especially the college-educated among them, have scored a series of union wins in the past few years among journalists, adjunct faculty, and graduate student workers, as well as among professionals at nonprofits and museums. The recent successes in unionizing Starbucks also included many young college-educated workers.

None of those efforts approaches the scale or visibility of the election win at the Staten Island warehouse. It’s tempting to compare the Staten Island win to the landmark 1937 victory of the United Auto Workers in Flint, Michigan, when General Motors granted recognition to the UAW after a legendary months-long sit-down strike. But while that victory took place two years after the passage of the National Labor Relations Act, a pathbreaking law that established the right to unionize, the ALU’s win was in a starkly different context: it succeeded despite the law, not because of it.

Now, I actually agree with most of this analysis, especially around the type of worker presently motivated to unionize. But the other major difference between Flint and Amazon is that with Flint, GM caved and signed a contract and I’ll be shocked in Amazon signs a contract with workers before the 2024 elections. Again, there is different context.

The bigger issue is the need to let movements breathe. When we start making big comparisons each time we have a victory, we end up comparing fragile movements to the glories of the past (which were of course fragile movements when they first won too) and for me, this really reinforces the idea that the past was better and filled with better activists. It’s all about context. The Amazon vote is huge. In fact, it’s the biggest private workplace to vote for a new union since the late 70s, which is more amazing for how horrible the last 40 years have been for unions than anything about the Staten Island victory per se. But it’s one vote at one facility against a recalcitrant company that is going to resist acquiescing to this for as long as humanly possible.

It’s an early win. We should celebrate. Also, everyone involved in this is flying by the seat of their pants. No one knows where this is going or what this will look like in 12 months, not to mention a decade. Let’s just let them figure it out, provide assistance where we can, and encourage more organizing. We can figure out how important it all is later.