Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,048

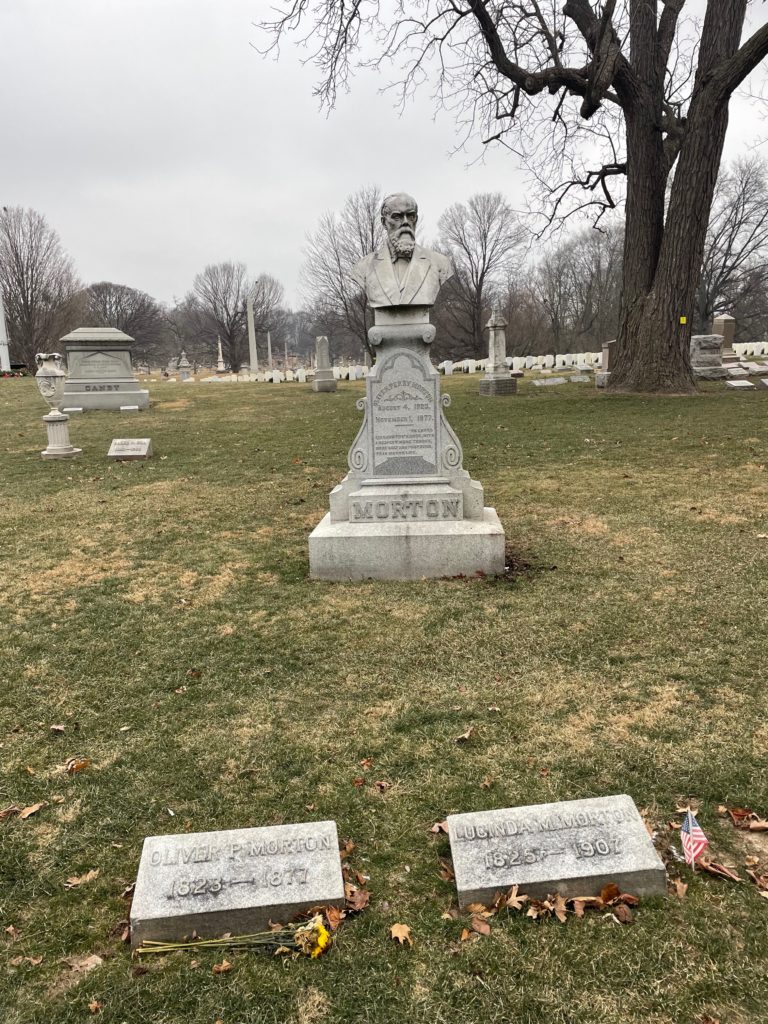

This is the grave of Oliver Morton.

Born in Wayne County, Indiana in 1823, Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (mouthful of name!), Morton was raised by his maternal grandparents after his mom died when he was 3. As a teenager, he worked for an apothecary and then went into the hat business. He hated that too and got out to go to college at Miami University in Ohio. He only attended for two years but that was enough and then he passed the bar in Indiana in 1846.

It wasn’t long before Morton realized the law was the best way into politics. He got elected as a circuit court judge in 1852 but realized he couldn’t earn any money that way so he quit. At first he was an anti-slavery Democrat but those were dying out fast and he became a Republican right about the time the party was formed in 1854. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was the last straw for him, as it was for many northern Democrats. Pro-slavery Democrats expelled the antis from the 1854 state Democratic convention, which definitely sealed the deal. Morton rose fast in the state Republican Party and was its candidate for governor in 1856. He barely lost that race, not bad given how new the Republicans were. In 1860, the Republicans were deeply divided between conservative economic Whig types and anti-slavery former Democrats. As a general rule, the former Democrats tended to retain their disgust with the South and the Slave Power a lot longer than the old Whigs did, who really always cared about pro-business policies more. So what happened was a package deal. Morton was to run as lieutenant governor while the conservative Whig Henry Lane ran as governor. Then, when Lane won, he would then be selected to go to the Senate and Morton would become governor. This worked and that’s what happened.

Morton was one of Lincoln’s biggest allies in a statehouse during the Civil War. During his six years as governor, he was staunchly pro-Union in a state with a Democratic Party that was increasingly playing with treason, especially in the state’s southern end. He had long thought that a civil war was inevitable between the regions and he immediately prepared his state to fight. He established a state arsenal and named only strong anti-slavery people to key positions. Morton was known for absolute political ruthlessness with the pro-slavers. Lincoln was not. He was always a compromiser. The difference between the two actually falls in favor of Morton. Lincoln always believed that most southerners really still wanted to be members of the United States. Morton knew this was a dream. He knew the only way to deal with treason was through harsh measures and crushing the rebellion. He was right. Lincoln was a little outraged by Morton’s methods though. But Morton knew that he couldn’t let the large pro-southern contingent of his state have any leeway or they would overwhelm him. It got harder when pro-slavery forces came to control the state legislature after the 1862 elections, another sign that Lincoln and his war was never very popular with much of the North. Meanwhile, Morton just figured it was a war so he simply ignored both the legislature and the state’s constitution. He was able for instance to raise millions in private loans to fund the state’s participation in the war, completely bypassing the legislature. They didn’t like it. So Morton just said they were traitors, which was pretty close to being true. Morton also used the state militia to suppress radical conservative Democrats and even send in the militia to the Democratic Party convention and arrested a bunch of the traitors. So you can see why this made Lincoln nervous.

The thing that helped Morton survive all this politically is that, very much unlike the vast majority of his fellow Republican leaders, he was in no way corrupt. All the money borrowing was done completely on the level, clear to the public, and all of it was paid back. So a reputation for honesty definitely kept him going. Democrats tried so hard to pin corruption charges on him but failed pretty miserably. He won a full term of his own in 1864, though he had a stroke the next year and had to go to Europe for awhile to try and recover. He never really did. But he remained an active politician as long as his health lasted.

In 1867, Indiana Republicans decided to send Morton to the Senate. He couldn’t stand any longer, but he could still speak fairly well and was known for giving an effective speech. Not surprisingly, Morton was a hard-core supporter of Reconstruction, demanding swift military measures against the traitors still marauding in the South and killing the freed slaves. He came around to supporting Black male suffrage after the war, after earlier having opposed the idea. That he wasn’t running for governor anymore probably helped him change his mind. After all, the reason the Fifteenth Amendment was required was that northern states were routinely voting against Black male suffrage at the same time that the military was enforcing it in the South. Morton also vigorously supported the impeachment of Andrew Johnson and was angry when he was acquitted by his colleagues. When Grant became president, Morton was effectively his floor leader in the Senate. An expansionist, he was a big supporter of Grant’s scheme to annex Santo Domingo to the United States, which was halted by Morton’s usual ally Charles Sumner.

Morton was also a fan of creating a modern financial system that included more paper money. He also authored a pro-inflation bill that would have helped debt relief, huge in Indiana. It passed Congress but Grant, a hard money man, vetoed it. Morton’s name was thrown around for the 1876 Republican presidential nomination. But his belief in paper money was way too radical for the Republican capitalist kingmakers. Also, he was getting pretty sick. He was still extremely active in his last months, being one of the leaders to ensure that Rutherford B. Hayes become president in the disputed election of that year. But while investigation bribery charges against Oregon senator La Fayette Grover, he had a massive stroke and died a few months later. He was 54 years old.

Oliver Morton is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Indiana.

If you would like this series to visit other people sent to the Senate in 1867, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Garrett Davis is in Paris, Kentucky and James Harlan is in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, which I suspect is neither mountainous nor pleasant. Previous posts in this series are archived here.