This Day in Labor History: November 13, 1887

On November 13, 1887, British police busted up an unemployment march that also had strong Irish nationalist leanings, leading to a violent battle in streets between the protestors and the cops. Bloody Sunday became one of the iconic moments in British labor history.

In the U.S., we talk about the Panic of 1873 as an exclusively American phenomenon, but it really wasn’t. If anything, it had longer lasting effects in Great Britain and most of the late 19th century was pretty rough for the working class. Food was cheap, but it also led to rural unemployment and migration to the cities, where jobs weren’t that good and didn’t pay that well. On top of this, the rising agitation for Irish independence was big in the working class, which was heavily Irish since the potato famine drove so many migrants to England. That split the Liberal Party and allowed the Tories to dominate politically. The Tories had no tolerance either for unemployment marches or Irish nationalism.

By the mid-1880s, unemployment marches became more common in London’s East End. These were usually infused with Irish nationalism, but attracted Marxists of various stripes seeking to organize for more widespread change, which many of the Irish were quite open to considering.

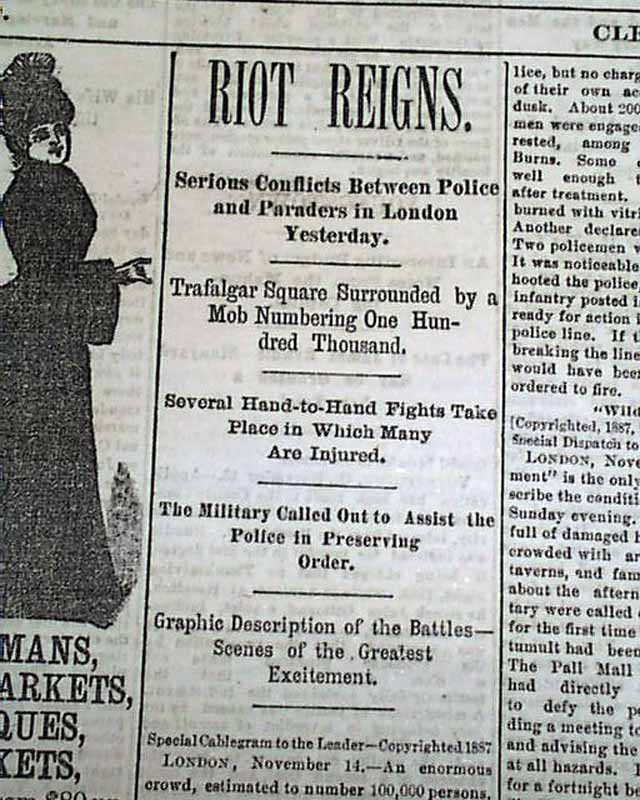

On November 13, the unemployment marches decided to have a big rally at Trafalgar Square, which was not only a key spot in London but also considered the dividing point between the working class East End and the posh West End. There were already a history of rallies in the space going back to the summer. The rich were getting sick of seeing this Irish trash, as they might put it, in their square. Beginning on October 17, police cracked down on the protests. That just led to more protests, as this became about free speech as well as workers’ rights and Irish nationalism. On November 8, Sir Charles Warren, Commissioner of Police, banned all rallies in Trafalgar Square. The protestors had no intention of obeying.

So on November 13, about 10,000 protestors showed up. But on top of that was another 30,000 largely sympathetic spectators who were on the edges of marching themselves. Among them were many of the nation’s leading radicals, including George Bernard Shaw, Eleanor Marx (daughter of Karl), Annie Besant, and William Morris. The British government was scared of these marchers. They sent 2,000 cops to police the demonstration. They also had volunteer constables, basically local anti-worker thugs. One of them, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, who would later be one of the leading newspaper publishers in the country, later remembered about his thuggery:

When the unemployed dockers marched on Trafalgar Square, where meetings were then forbidden, I enrolled myself as a special constable to defend the classes against the masses. The dockers striking for their sixpence an hour were for me the great unwashed of music-hall and pantomime songs. Wearing an armlet and wielding a baton, I paraded and patrolled and felt proud of myself.”

Now that’s some class condescension!

The leaders of the rally began to march toward the police so that the action could continue into the square proper. The cops and the volunteer constables just started beating the hell out of them. Horseback cops rode through the crowd, terrorizing the workers. Clashes between the workers and the cops continued all day

The next week, workers tried to rally again. Once again they were beaten. At least one person died, a clerk named Alfred Linnell, trampled by a police horse.

In the aftermath, a couple of the march’s leaders, John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham, served six weeks in prison for their part in it. There was a police investigation. The conclusion was the truncheons used by the cops weren’t strong enough, as many had broken while beating people. As for the beatings, that was outright approved by the investigation. It would take a lot more working class revolt for the British government to give workers any rights.

This is the 415th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.