Land Acknowledgements

The latest white liberal fad for meaningless diversity is the land acknowledgement. Theoretically, this is a good thing. Remembering that this land was stolen from Native peoples is in fact important. But what does it mean once it becomes a rote thing? Is there any power behind it? What is the change we are arguing for when we discuss this? Or is this just another way to show we like “diversity,” when we are usually in all-white spaces and talking about land acknowledgements requires absolutely nothing of us?

In other words, there is a big difference between diversity and power. Diversity is the equivalent of liberals being excited that Condoleeza Rice is Secretary of State. Finally, we have reached a point in this nation when a Black woman can also order the murders of Iraqis. Power is about changing the structures to destroy the system of colonialism, capitalism, and patriarchy that continue to create difference today.

In other words, land acknowledgements are just fine if they lead to actual challenges to power. Let’s say you are a college campus, where land acknowledgements are going to be super popular. If you have a bunch of white liberal faculty who want to note that we are on X tribe’s land, but it just becomes a rote recital that has no meaning behind it, then I don’t see what you are doing but making yourself feel good (or feel guilty, which is certainly a way that some white liberals like to feel good). But if your land acknowledgement comes with a demand for free tuititon for Native students, admission quotas to increase Native enrollment, Native-run parts of campus, Native Studies departments, state compensation to the tribes for loss of land, requirement of Native Studies courses, etc., then OK! That’s working to do something about it.

I think this differentiation is critical. That’s because a lot of how this is acting is reality is a combination of using the tribes for a cynical benefit, placing pressure on Native people to be what they are not, and even stripping their humanity by engaging in gross stereotypes about them being “caretakers of the land” and whatnot. Finally, some Native leaders are snapping back at the liberals engaging in meaningless land acknowledgements.

Land acknowledgments are generally meant to acknowledge the Indigenous history of the land one is on. But for Michael Lambert, many such statements don’t adequately reflect how Indigenous peoples were forcibly removed from their lands.Lambert, associate professor of African Studies and Anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says such statements often refer to Indigenous peoples as the original “stewards” or “custodians” of land that is now occupied by another entity. To him, that language obscures the fact that tribal nations were sovereign over those lands and that they weren’t just caretakers.

“It’s like, ‘Oh gee, thanks for taking care of the land so well. We promise to do a better job in the future,'” says Lambert, who is an enrolled citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. “It comes across as a very painful denial of exactly what happened.”Some land acknowledgments also fail to acknowledge the traumas that accompanied Native people being removed from their lands, Lambert adds.”That process of transferring control from the Indians to the non-Indians was fraught with conflict, it was violent, it involved murder in some cases and extreme pain,” he says.Another issue Lambert sees in some land acknowledgments is that they can suggest Indigenous peoples — and by extension, issues of land dispossession — are a relic of the past, when Native communities are living many of these realities today.”Land dispossession is continuing,” he adds. “It hasn’t ended.”

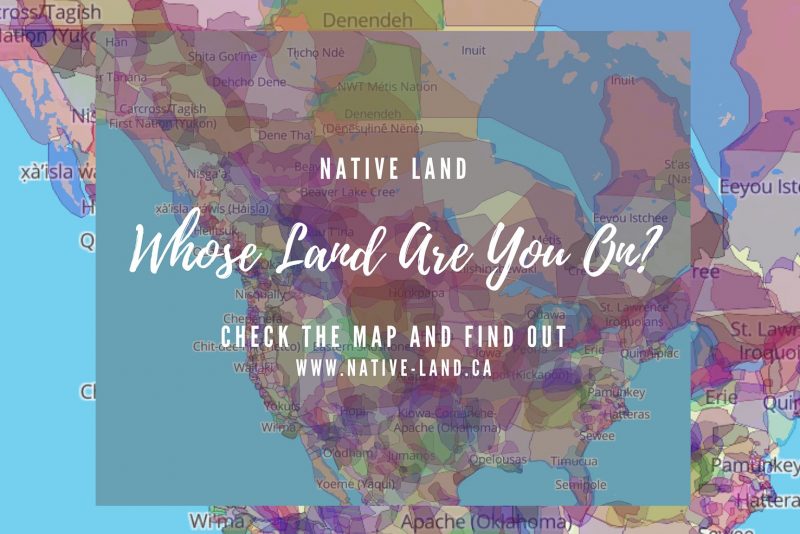

Necefer, a member of the Navajo Nation, recalls a recent experience he had while on a conference call, during which each participant was asked to recognize the Indigenous people whose homelands they were calling from.The exercise felt uncomfortable and awkward, Necefer wrote in Outside magazine. He was calling from his mother’s house in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which Navajos have considered their homelands for centuries. But it struck him that many Pueblos in the area would dispute those claims — and a brief land acknowledgment would oversimplify what was actually a complex and contested history.He notices a similar lack of nuance in the ways people determine whose land they’re on. Native Lands Digital, a commonly used app run by a Canadian nonprofit, allows users to input an address to see what tribal nations lived there. But the map only includes the names of those tribes, without the history or context around potentially contested claims to the land. Some of the tribes listed are “functionally extinct,” he says, and are grouped in with nations that continue to exist in the area. (Native Lands Digital, which did not immediately respond to questions from CNN, says in a disclaimer on the site that the map is “not perfect” and is a work in progress.) Many people who use the app tend to approach it as the endpoint rather than the starting point, he adds.

“I could see that people are just copying and pasting this stuff without really looking into the details,” Necefer tells CNN.In other cases, land acknowledgments might refer to “stolen land” — a seemingly well-intentioned phrase designed to convey how Native people were driven from their homes. But while some tribes might agree with that characterization, Necefer says, others view the situation differently: Rather than land belonging to people, people belong to the land.”Landscapes’s elements make up the blood, bone, and flesh that animate our bodies. When we die, we return to the land and turn into the trees, rocks, and water that once gave us life,” he wrote in Outside. “The phrase ‘on stolen land’ can unknowingly erase these cultural views.”

The article goes into other issues with land acknowledgements as well.

Again, the point of these politics is not to make you feel good or bad. The point is to provide fundamental change. Acknowledge the land all you want. But you also need to make real demands on your institution to erase the oppression of Native people in 2021. Otherwise, it’s just diversity rhetoric that does nothing.