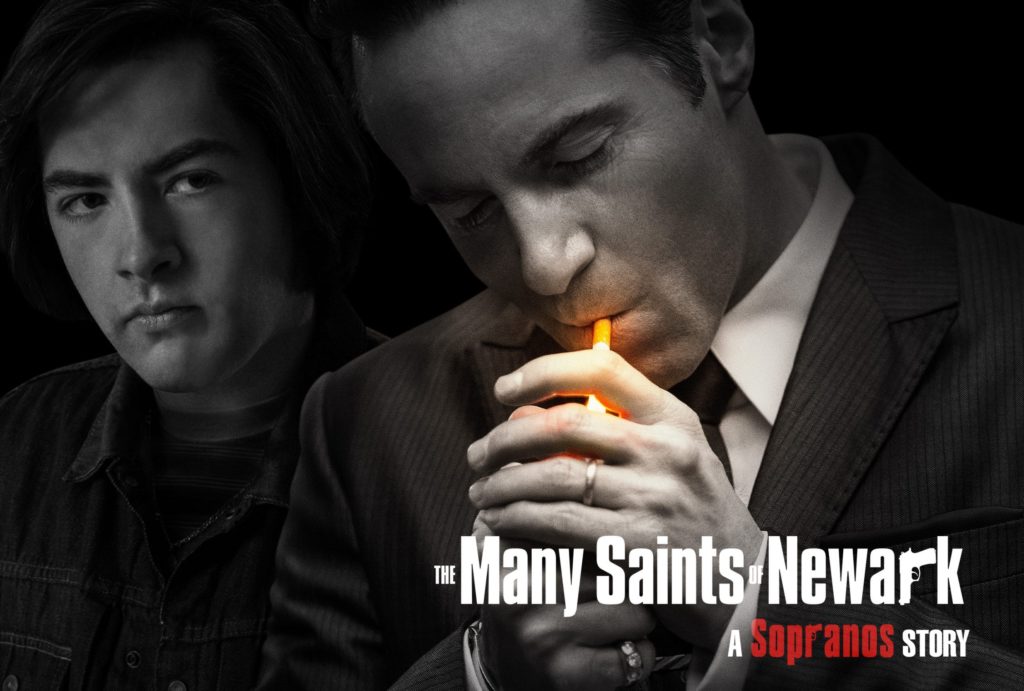

The Many Saints of Newark

In the interest of full disclosure, I should probably say that I was skeptical about the idea of a Sopranos prequel movie—and especially one focused on Tony Soprano’s teenage years—from the moment it was first floated. The essence of The Sopranos was fruitless regret and unrealistic nostalgia. That’s what made it a brilliant work even to people like myself, who had very little interest or even grounding in mob stories. What made it, in many ways, a metaphor for modern American life (and what is apparently making it attractive to younger millennials and zoomers who are watching it for the first time, a cohort that, even more than their elders, believes that they’ve “come in at the end”). Going back to that imagined golden age seemed completely beside the point, a choice that would eliminate all the things that made The Sopranos distinctive as a story about mobsters, and leave only a recreation of the stories it was—with rare insight and intelligence, and unsparing honesty—responding to.

So you might want to take it with a grain of salt when I say that, having watched The Many Saints of Newark, I feel entirely vindicated in my reaction. That the film is pointless and unimpressive, a generic mob story whose interest to Sopranos fans begins and ends with petty background-filling, the kind of fan service you’d expect this series to be above. It lacks the weirdness, dark humor, and poetry that made The Sopranos special. It tells us nothing new about Tony Soprano or the figures who have loomed large in his life. Its one major addition to the Sopranos canon, the fleshing out of Christopher’s father, Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola), feels like a watered-down, sped-up version of character arcs that were already done better with both Tony and Christopher.

Saints does at least do a few unexpected things. For one thing, the film is narrated, from beyond the grave, by Christopher, which is about as close as it ever comes to the show’s constant flirtation with magical realism. For another, despite all the press attention that Michael Gandolfini has received for stepping into his father’s most famous role, teenage Tony is a rather minor character in this story (in fact, for the first half of the movie, set in 1967, Tony is a tween played by William Ludwig; Gandolfini only appears when the film flashes forward to the early 70s). Its most interesting choice is to focus much of its story on the growing tension between the Italian mob and black criminal gangs, who over the course of the movie transition from working as the former’s runners to staking out their own territory. This transformation is juxtaposed with increasing racial tension, police brutality, and white flight, which is a nice callback to the way that The Sopranos always viewed its criminal characters as a microcosm of American society. (In one of the film’s few genuinely funny moments, Leslie Odom Jr.’s Harold McBrayer, a former employee of Dickie’s, is inspired to become a mob boss in his own right by watching a black power and consciousness raising lecture.)

Like any other interesting idea raised by this movie, however, this subplot isn’t given enough room to breathe and develop, and ends up being unceremoniously dropped as soon as the white heroes decamp for the suburbs. In fact, the kindest thing I can say about The Many Saints of Newark is that it might have worked better as a television series. With space to develop its characters and pepper in those glimpses of humanity and fallibility, of tedium and stupidity, that made the show so special, its story might have rivaled the original’s. At feature length, it feels like a Sopranos highlights reel, one that contains only the moments of violence and significant event, without the connective tissue that made the original show so heartbreakingly humanistic. Take, for example, the subplot about Dickie’s mistress, Giuseppina (Michela De Rossi). Her rocky relationship with Dickie, and fatal misreading of both the man that he is and the depth of his commitment to her, are an obvious parallel to Adrianna’s. But absent the slow buildup of tension and complexity that made that storyline one of the show’s most gutting, it just feels like a story we’ve seen a thousand times before in mob movies (not to mention, one that ultimately revels in violence against women without giving sufficient space to their humanity).

Dickie himself is the sort of character you could imagine gaining a greater complexity in a different storytelling format, and perhaps the only justification for Saints’s existence is its attempt to reveal that the men the adult Tony rhapsodizes about and describes as “the strong, silent type” were no less troubled and conflicted than he was. Over the course of the film, we learn about Dickie’s rocky relationship with his father (Ray Liotta), watch him do terrible things, then try to make up for them with grand gestures (including reaching out to his incarcerated uncle, also played by Liotta, who becomes this story’s outsider truth-teller, a sort of counterpart to Dr. Melfi), and ultimately fail, because he does not grasp the fundamental moral void that is his life, or the enormity of what he would have to do to fix it. But again, we’ve seen this story before, and nothing about the execution here rivals The Sopranos or finds new notes in it. All it does is fill in some gaps in Tony and Christopher’s backstory that weren’t really necessary to appreciate either of their character arcs.

In fact, Saints’s biggest problem might be that it doesn’t really know whether the focus of its story is Dickie, Tony, or even Christopher. The film’s poster loudly proclaims that it is coming to answer the question “who made Tony Soprano”, and its story fleshes out the hints we’ve gotten from the show, that Dickie was Tony’s second father. (Jon Bernthal’s Johnny Boy Soprano is absent for much of the movie, but even when he’s there, it’s strange how little space he takes up, either in the story or in Tony’s life.) But, well, we already knew the answer to that question, and it was simultaneously not very interesting—Tony is the way he is because he’s smart but lazy, able to see that his life is not what he wants it to be, but always drawn to the path of least resistance—and, in the parts of it that were interesting or at least unexpected (chiefly his relationship with Livia), already sufficiently explored by the show. (Vera Farmiga’s turn as Livia reminds us both how toxic she was and how honestly she came by her depression and mood swings, but it’s still a reflection of what the original show did, not a character in its own right.)

Saints eventually tries to argue that it was in Dickie’s power to set Tony on a better path, and that his death—which ironically comes as the result of events that he set into motion—foreclosed that possibility. But, well, I don’t buy it. Sure, teenage Tony says that he wants to go to college and tries to steer clear of “this thing of ours”, but he says it in the same way that some kids say they want to be an astronaut. Whether because of some natural tendency or the way he’s been raised, he’s got no follow through, and it’s hard to imagine that, had Dickie lived or done something different in his mentorship of Tony, The Sopranos would have never happened. In fact, The Sopranos itself repeatedly came out against this fantasy. In how he raised his children and how he mentored Christopher, Tony repeatedly acted as if he could set them on the right track with a few well-chosen words. And the show would then go on to reveal that what actually mattered was what he showed them every day, how he behaved towards them and other people, and the culture he raised them in.

What’s left, then, is in the realm of Easter eggs. The actual revelation of who killed Dickie Moltisanti is pretty funny. It explains quite a lot about Paulie Walnuts to know that in his youth, he looked like Billy Magnussen. The constant ironic callbacks to the fact that Tony is going to kill Christopher (and that Dickie’s actions will indirectly lead to the death of his only son) are overdone but still have some force. And when “Woke Up This Morning” starts playing over the film’s final glimpse of the teenage Tony, it’s hard not to get excited even as you’re rolling your eyes all the way back into your head. But all of it feels like a pale shadow of the original show, answering questions that didn’t need to be asked, and missing out on all the things that made it remarkable.