This Day in Labor History: August 25, 1935

On August 29, 1935, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters signed its first contract with the Pullman Car Company, breaking that company’s long anti-union history and providing a breakthrough for Black workers in America. This successful campaign laid the groundwork for much larger campaigns for Black labor organizing over the next several years.

Founded in 1925, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters provided a key tool for Black resistance in the days of the Great Depression. Being a porter was absolutely a service job for whites with all the denigration that came with in the Jim Crow era. But it was also as good a job as Black men could get. It allowed them to travel and spread information around the country. A. Philip Randolph, a socialist organizer who had previously organized Black elevator operators, organized the sleeping car porters in 1925. But that did not mean that the Pullman company was going to give them a contract. It was a long time since George Pullman crushed the 1894 Pullman strike with maximum violence, but Pullman was still a strongly anti-union company.

The Great Depression was hard on the Porters as well because it was hard on the railroad industry. People stopped traveling and thus porters were laid off. It hoped to strike in 1928, but was not strong enough as a union to do so. By 1930, it was barely hanging on period. By 1933, the BSCP had all of 633 members. But the rise of New Deal labor legislation led to an expansion in organizing, as it did for unions around the country. By 1935, union membership rose to 4,165.

The National Labor Relations Act, though passed in 1935, was not how the Porters got their union. Rather, it was the Railway Labor Act of 1934, which strengthened union rights on railroads. Not seeing any way out, the company finally caved to unionized porters after a month of negotiations. That first contract reduced the hours of workers from 400 hours a month to 240, which is a huge gain, along with significant wage increases. Of course, the real win was union recognition. The Chicago Defender, the leading Black newspaper in the city, called it “the largest single financial transaction any group of the Race has even negotiated.”

This was a historic moment. But the way it happened was even more important. The Porters had engaged in a campaign based around Black manhood, a critical theme in Black organizing and discourse for a very long time by this point and one that would remain so in labor organizing for decades. What this meant was the ability to stand up for yourself, protect and provide for your family, and be treated with respect, all of which white society and white employers denied Black men. It explicitly linked labor and civil rights, avoiding any kind of class over race or race over class rhetoric that was more ideological than lived for real workers. There were all sorts of rent strikes and other organizing happening in the Porters’ home base of Chicago, not to mention other cities, in the 1930s, and all of these influenced the union’s growth.

Pullman resisted this all it could. It employed spies that reported back on the organizing, including the ways in which the BCSP participated in community organizing in Chicago. But the momentum was with the Porters and other Black workers. In fact, the Porters and Randolph especially pushed the NAACP hard on these issues during these years, to the point that by 1941, Walter White was forced to use similar rhetoric in support of striking Black workers that were part of the River Rouge strike that organized Ford after several years of failures. That was very unlike the cautious legal strategies and respectability politics of the NAACP. Key to all of this was the National Negro Congress, led by Randolph and founded in 1936, which pushed a leftist coalition politics in the Black community, including communists and including interracial campaigns. This helped set the tone for the next decade of Black politics, which Randolph and the Porters would continue to lead, despite the fact that porters on a railcar was a dying profession in the face of the automobile and then the passenger airplane. The Porters Citizens Committee led many fights in Chicago and around the nation, even as Randolph was skeptical of the communists.

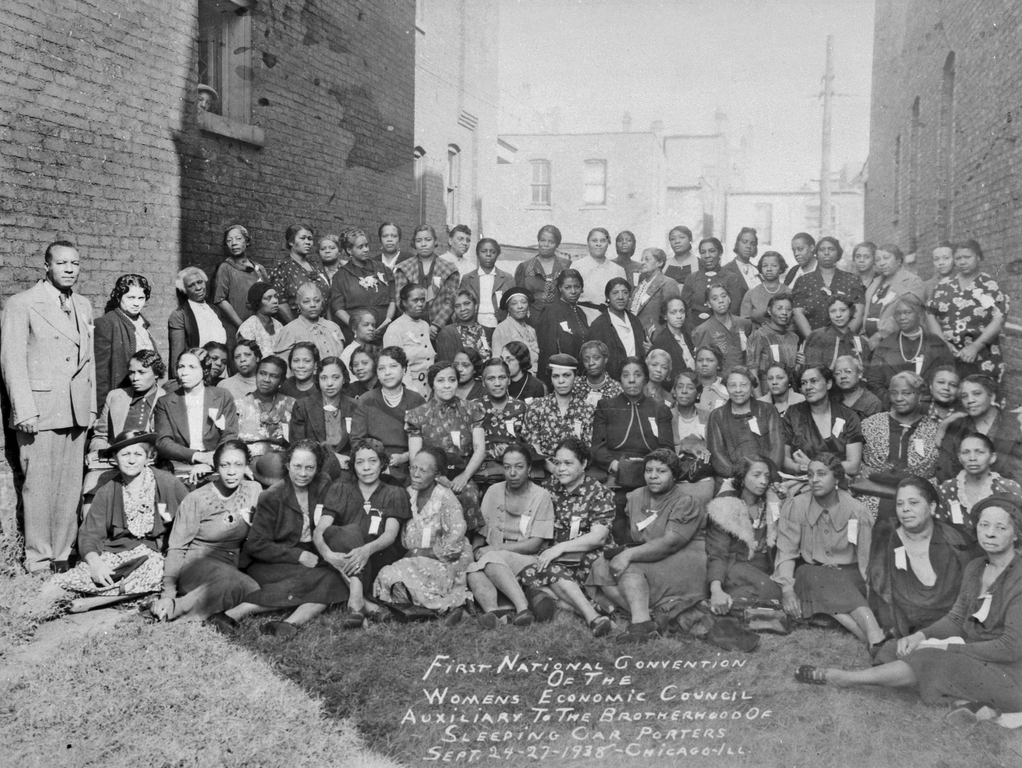

This all played out in the rise of the CIO, where Chicago was a critical city. The United Packinghouse Workers of America, for instance, were a union with a large Black population and one that would develop real interracial leadership, unlike many unions with smaller Black workforces. The National Negro Congress formed a labor committee, again with heavy Sleeping Car Porter influence, to spearhead labor organizing in that city, not only in the packinghouses but in steel, which employed large numbers of Black workers. For example, Helena Wilson, who headed the Chicago Women’s Economic Council within the BSCP, was picked to help lead the organizing drive at the Inland Steel Company. In this case, organizing women who were in families with steelworkers led to the creation of a women’s auxiliary to the Steel Workers Organizing Committee and built support with key Black ministers. This kind of organizing in steel led the packing workers to demand the same from the Black community.

By 1940, Randolph was on the NAACP’s Executive Board and he was building on the previous decade’s successful organizing to start the March on Washington Movement to demand the integration of defense jobs, which forced FDR off his indifference to Black workers and to issue an executive order granting Randolph his demands.

In the end then, this one union victory, with as few numbers as it was, helped create the conditions for mass Black worker organizing over the next several years, making Randolph arguably the most important and effective civil rights leader of the period, and laying the larger groundwork for the postwar upsurge in Black activism.

I borrowed from Beth Tompkins Bates, Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America, 1925-1945 to write this post.

This is the 406th post in this series. Previous posts are archived here.